Kuna (ethnicity)

The Kuna (also Cuna , self-name Dule , "human", in Colombia Tule ) are an indigenous ethnic group in Panama . They settle in the territory of Guna Yala (also called San Blas ), which includes the north-eastern Atlantic coast of Panama with its offshore islands and a strip of mainland several kilometers wide as far as the Colombian border. About 1500 kunas live in the mountains of the Bayano region on the Chepo river . Most, however, live along the approximately 200 km long coastal strip that extends from the settlement of Armila, which is near the Colombian border, to western Mandinga. The number of kunas living here is around 30,000. There are also some small settlements in the Colombian rainforest along the Urabá Gulf .

The majority of the population of Guna Yala is located on around 50 of the 370 coral islands off the coastline and 11 settlements in the rainforest of the mainland. The size of the population ranges from 100 to 4,000 people, depending on the size of the settlement. The Kuna language , along with Ngäbere, is one of the two most widespread Chibcha languages .

Emergence

Today's Panama became a strategically important transshipment point for the Spaniards as early as the 17th century and the first conflicts with the indigenous population arose. The Kuna ethnic group, who originally settled near the Gulf of Urabá in what is now Colombia and fled from the Spanish into the jungle on the Gulf of Darién , tried to counter the dominance of the colonial rulers. They allied themselves with the English, Scots and French, as well as with privateers of the Caribbean and maintained trade relations with them. Together with the Jamaicans, they organized an uprising on the mines of Daríen, which had been exploited by the Spanish, which lasted from 1775 to 1789 and decimated the Kuna population. Their settlement area shifted from the Gulf of Daríen to the Atlantic region and they now settle about forty islands of the four hundred islands of the San Blas Archipelago , which lies east of the Atlantic opening to the Panama Canal and extends to Colombia.

After the decisive battle at the Bridge of Boyacá, in which Simón Bolívar won the day against the Spanish, Panama declared itself independent from Spain in 1821 and at the same time its annexation to Greater Colombia. The Kuna tried to obtain a declaration of independence from the new government. In part, they succeeded in doing this through “de facto independence”. In 1871 a decree created the Comarca Dulenega, an administrative and territorial unit. Thus the Kuna were effectively independent until 1903 and carried out their own foreign trade, especially with the British of the colony of Jamaica. At the beginning of the 20th century, the USA sought a guarantee of the rights to use the interoceanic canal under construction. They drove Panama's aspirations for independence from Greater Colombia and in 1903 the state of Panama was founded with the United States as the protecting power. The young state tried to create a national identity and incorporate the Kuna. There were attempts at proselytizing, regulating maritime trade in San Blas and, above all, territorial conflicts. The Comarca Dulenega of the Greater Colombian Constitution no longer existed for the Panamanian government. A district chief was appointed for San Blas, who should eradicate all "barbaric" customs through police officers. In addition, a western dance event became compulsory to promote marriages between Kuna and Panamanians.

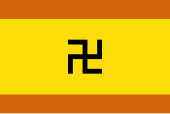

The illustrated swastika-like symbol with hooks pointing to the left has its own origin. It represents an octopus who, according to local tradition, created the world.

In February 1925, representatives of the San Blas Islands met at a congress at the instigation of the United States and declared their independence from Panama in a written declaration. An uprising was carefully planned and ended in a week-long riot in which 27 people were killed - the Dule Revolution. In the end there was a negotiation with the Panamanian government and the “contract of the future” was signed. The Kuna were supported by the USA, which had considered establishing another satellite state alongside Panama. This gave the Kuna administrative rights over their territory, recognized in return the sovereignty of Panama and initially accepted the introduction of the national education system, which was not undisputed. In 1957 the local government was also recognized. A new constitution gave the indigenous peoples the right to representation in the Panamanian parliament from 1983.

organization

The political organization of the Kuna is a combination of their traditional customs and Panamanian institutions. All 52 Kuna village communities are autonomous and this autonomy is ensured by the independent economy. Once a year there is an assembly that is the highest decision-making body - the General Council. The head of the respective village parliament is elected by the male population. There are also daily meetings in the meeting house to discuss upcoming disputes, problems, and decisions. There are representatives for the various activities in the village. The economic activities are very modern, such as the tourism sector, the handicrafts or the marketing of lobsters, crabs and squid. The Kuna elect three MPs to the Legislative Assembly of Panama, which effectively enables them to participate in the development of national policy. The MPs must, however, belong to one of the major national parties and so stand in conflict between the decisions of the General Council and the line of the party to which they belong. The accumulation of capital runs counter to cultural principles and does not increase prestige. Capital that is acquired through trading in handicrafts, for example, is invested in one's own company, consumer goods are purchased or the children's studies in Panama City are financed.

aims

The Kuna strive to maintain their territorial autonomy. One problem is that the area of the Kuna has not yet been measured, which means that there are always disputes over property. After being driven from their land, large landowners refer “campesinos” to “Kunaland”, which they believe is fallow. The land reform that has not been carried out so far turns small farmers into landless people. They clear the rainforest and do intensive agriculture. When the soils are depleted, they first operate cattle farming and finally - when the soils are completely eroded - new areas are made usable. The Kuna are calling for land reform and founded the “Pemaski” project. They have mapped the clearing of the primeval forest by the settlers and are reforesting eroded soils. They also measure the land of the Comarca of San Blas, patrol the forests to avoid illegal slash and burn and expel settlers from Guna Yala.

American investors have already shown interest in some Caribbean island groups, but were able to be driven out by the Kuna without the Panamanian government intervening. There are bays near Colón where cruise ships anchor several times a month. The Kuna are active in the tourism sector, but want to avoid settlement.

Networks

The social movements in Panama are very weak compared to other countries in Latin America. Although Panama has been officially independent since 1903, limited state sovereignty continued until the end of 1999. The "de facto dictatorships" under Torrijos and Noriega, as well as the "Just Cause" operation and the associated occupation and suzerainty of the Americans contributed to this.

The relationship of the Kuna to other population groups in the region has historically been under the sign of autonomy. One example is the trade relations with the Caribbean privateers.

Identity and Opposition Principles

Maintaining one's own culture is very important to the Kuna. They are directed against being incorporated into society and emphasize the diversity of cultures. This includes the right to self-administration and the right to own territory. This is what the kuna have achieved.

Oppositions of the Kuna include state authorities and large landowners as well as landless mestizos and Afro-Panamanians who are penetrating the Kuna territory. Already in the 19th century there were violent disputes, for example after the land invasion as a result of the railway construction or the rubber war in 1870. But there have also been some violent conflicts in recent years.

The Kuna are guaranteed essential points by the constitution: the equality of marriage carried out according to traditional rites with marriage under civil law, the recognition of traditional healing methods (ethnomedicine) and the Ibeorgun religion as the religion of the Kuna. Matriarchy prevails among the Kuna, and the chosen man must move to the island and the woman's hut when they marry.

Textile handicrafts are an important characteristic of their ethnicity today. The so-called Molas or Molakana are colorful cotton fabrics with a wide range of motifs and shapes, decorated by application techniques. They form an element of the women's costume and are now also produced for the international market.

The Kuna have a special relationship with their country. It cannot be bought, sold, or leased. The Kuna see it as the inheritance of their people and the acquisition, exploitation and use must be compatible with this status.

For this reason, too, sustainable development has the highest priority. The NGO "Asociacion NAPGUANA" (The Association of Kunas United for Mother Earth) was founded in 1992 in order to be able to work in an international framework for the careful use of natural resources and for a general improvement in the living conditions of the indigenous population. ( http://www.geocities.com/TheTropics/Shores/4852/home.html ( Memento from April 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) )

Results

The Kuna were able to preserve their culture and identity like hardly any other ethnic group in South America - above all thanks to their autonomous status. In 1953, with the adoption of Law 16 for the organization of the Comarca Guna Yala, the Kuna received a special status that is not granted to any other ethnic group in Panama. Their form of self-administration is unique.

The Panamanian government accepted the Carta Organica, an internal constitution of the Kuna with a clear definition of the institutions. According to Article 113 of the Panamanian Constitution of 1983, the participation of the indigenous population groups is to be promoted and Article 116 guarantees “the collective possession of a sufficiently large area of land to ensure their economic and social well-being”. For some years now, the Guaymí have also been striving for autonomy and now claim an area of around 10,000 km² in the eastern provinces of Panama. The efforts of the Guaymí have so far been unsuccessful, especially due to the required participation in the profits from the extraction of mineral resources in the region.

The “Asociacion NAPGUANA” supports other indigenous groups in Panama economically and legally.

Culture

The Kuna have a pantheon of female deities. Medicine men act as clairvoyants and can supposedly enter the underworld in a trance . Talismans are common.

The wearing of septum piercings was common among the Aztecs , Maya and Inca for religious reasons . This tradition is partly continued today by the Kuna. Mostly gold rings are used.

The Tule in Colombia

The Tule belonging to the Kuna live in the Gulf of Urabá and the Darién region , especially in the Arquía ( Chocó ) and Necoclí ( Antioquia ) areas in Colombia .

In contrast to the Kuna of Guna Yala in Panama, who call themselves Makilakuntiwala , the Tule in Colombia call themselves Ipkikuntiwala . There are 1,166 members who live in an area of 10,087 hectares.

There are barely noticeable linguistic differences between the groups in Colombia and Panama.

literature

- Duke, Gaby. 2018: The Labyrinth of Life. The Kuna people off the coast of Panama , In: Blickpunkt Latin America, Essen, 2/2018, pages 6–13.

- Alí, Maurizio. 2010: “ En estado de sitio: los kuna en Urabá. Vida cotidiana de una comunidad indígena en una zona de conflicto ”. Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Departamento de Antropología. Bogotá: Uniandes. ISBN 978-958-695-531-7 .

- Alí, Maurizio 2009: " Los indígenas acorralados: los kuna de Urabá entre conflicto, desplazamiento y desarrollo "; Revista Javeriana, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Colombia, n.145 (julio): 32-39.

- Friedrich von Krosigk: “Panama - Transit as a Mission; Living and surviving in the shadow of the Camino Real and the Transisthmic Canal ”. Latin American Studies Volume 40; Vervuert Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1999.

- Rüdiger Zoller (ed.): “Panama - 100 Years of Independence; Scope for action and transformation processes of a canal republic ”. Institute for Spanish and Latin American Studies; ISLA, Erlangen 2004.

- James Howe: "Un pueblo que no se arrodillaba". Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies, South Woodstock 2004.

- Holger M. Meding: “Panama State and Nation in Transition (1903–1941)”. Latin American Research 30, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2002.

- Karin E. Tice: "Kuna, Crafts, Gender and the global economy". University of Texas Press, Austin 1995.

- Gundula Zeitz: “We don't get anything for free”. In: Inge Geismar, Gundula Zeitz (eds.): Our future is your future - Indians today; Luchterhand Literaturverlag, Hamburg (among others) 1992.

- Jesús Q. Alemancia: “The Autonomy of the Kuna”. In: Nidia A. Rodas and Elisabeth Steffens (eds.): Abia Yala between liberation and foreign rule - The struggle for autonomy of the Indian peoples of Latin America; Concordia, Aachen (among others) 2000.

- "Comunidades Indígenas - Un paraíso llamado Kuna Yala". In: ECOS de Espana y Latinamérica, Spotlight Verlag, edition: November 2003. pp. 24–26.

- Wolfgang Mayr: “Desirable Kuna Land - The Reserve of the 400 Islands in Panama”; In: POGROM 182; April / May 1995 edition; P. 24.

- Verena Sandner Le Gall: "Indigenous management of marine resources in Central America: the change in usage patterns and institutions in the autonomous regions of the Kuna (Panama) and Miskito (Nicaragua)". Self-published by the Geographical Institute of the University of Kiel, Kiel 2007, ISBN 978-3-923887-58-3 .

- Gerhard Drekonja-Kornat : "How the" white Indians "got the swastika". In: Américas (Vienna), vol. 31, year 2004.

- Kunsthalle Göppingen, Filseck Castle, 2012: "Molas, Textile Body Pictures of the Kuna Indians from the Volkens Collection , Karlsruhe"

- Kit S. Kapp : "Mola Art from the San Blas Islands", 1972

- Günther Hartman: "molakana. Folk art of the Cuna, Panama", 1980

- Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne, 1977: "The San Blas Cuna. An Indian tribe in Panama"

- Ann Parker & Avon Neal: Molas. Folk Art of the Cuna Indians, 1977

- Michel Perrin, 1999: "Magnificent Molas. The Art of the Kuna Indians"

- Edith Crouch, 2011: "The Mola. Traditional Kuna Textile Art"

- Mari Lyn Salvador, UCLA 1997: The Art of Being Kuna. "

Web links

- Amasipu : Maurizio Alí Photoblog about the Kuna

- Literature about the Kuna in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin

- (Tule in Colombia)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Åke Hultkrantz , Michael Rípinsky-Naxon, Christer Lindberg: The book of the shamans. North and South America . Munich 2002, ISBN 3-550-07558-8 . P. 90.

- ^ A History of Body Piercing throughout Society

- ↑ Alí, Maurizio. 2010: “ En estado de sitio: los kuna en Urabá. Vida cotidiana de una comunidad indígena en una zona de conflicto ( Memento of the original of July 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ”. Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Departamento de Antropología. Bogotá: Uniandes. ISBN 978-958-695-531-7 .