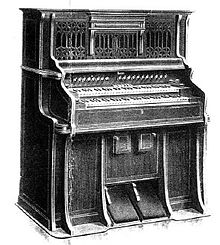

Artificial harmonium

The artificial harmonium is the highest quality type of harmonium that was specially designed for artistic solo use. An essential feature of the artificial harmonium is a "double expression" called wind pressure division, which is controlled with special knee levers (not to be confused with the knee levers of other types of harmonium, which have a different function). The double expression allows the bass and treble halves of the keyboard to be played at different volumes and dynamics. The arrangement of the artificial harmonium is type-specific and standardized, the wind supply is traditionally done with pressure wind.

history

Alexandre-François Debain (1809–1877) patented the classic French pressure wind harmonium in 1842 . Its further development into the actual artificial harmonium (French harmonium d'artiste or harmonium d'art ) is thanks to the French instrument maker Victor Mustel (1815–1890), who patented what he called "double expression" in 1853. The double expression was a further development of a similar device previously designed by Alexandre Martin de Provins, a builder from whom Mustel also took up other innovations, such as the percussion device (see above). Mustel's development of this instrument was intended to remove a number of restrictions that had existed with the previous In addition, a uniform type was to be created that would allow even demanding compositions to be played with a fairly uniform handling. Typical negative properties associated with the harmonium, such as the dynamic disproportion between the bass and treble register and the insufficient dynami cal differentiation should be eliminated with the artificial harmonium.

However, due to its high price and the great artistry that was required to play it, the artificial harmonium (in contrast to the suction wind harmonium ) never became a mass instrument. In addition, only a relatively small number of important composers such as César Franck , Alexandre Guilmant , Georges Bizet and Sigfrid Karg-Elert composed especially for the Kunstharmonium. On the other hand, however, the artificial harmonium brings out the specific advantages of the harmonium instrument, ie its entire tonal and dynamic wealth, in a special way. That is why the Kunstharmonium has recently become a valued instrument again in specialist circles.

Furnishing

According to the words of one of its most important composers, Sigfrid Karg-Elert (in: The Art of Registration , Part 1, Berlin 1911), a typical art harmonium should have the following technical equipment:

- a wind supply in the pressure wind system, ie in contrast to the more widespread "normal harmonium", the artificial harmonium does not classically work with suction wind (although after 1900 a few suction wind artificial harmoniums were constructed);

- a keyboard range from C – c 4 , with a division into a bass half from C – e 1 and a treble half from f 1 –c 4 , for each of which there are separate registers (the “normal harmonium” on suction, on the other hand, has a keyboard range of ContraF – f 3 with division at h 0 / c 1 );

- an expression train that guides the wind directly to the tongues, bypassing the compensating magazine bellows. This allows you to better influence the volume, depending on how hard you step on the scoop pedals;

- the "double expression", which is controlled by two knee levers for the bass and treble halves (and not to be confused with the aforementioned expression train). The double expression causes different degrees of opening of the two inlet valves to the tongue chamber and therefore also influences the volume;

- the Métaphone , a device that closes keys at the rear of the artificial harmonium; this makes the sound of the rear games (nos. 3 and 4 below) darker and richer;

- the prolongement , a "key chain" for the twelve keys of the lower octave, which they hold in the depressed state and in this way enables organ points . The prolongation can be temporarily overridden by a device for “heel triggering” on the left pedal , called a talonnière , as long as its stop is pulled (because you don't want to hold every note that plays into the low octave for a long time);

- The Forte-Fixe and the Forte-Expressif , two trains that open the Forte flap of the artificial harmonium; the Forte Fixe opens this invariably wide, the Forte Expressif, on the other hand, depending on the wind pressure;

- The Grand Jeu (“Volles Werk”), a train that sets the first four registers (nos. 1–4 below) into action at once;

- The percussion , a device in which the tongues of the first 8 'register (no. 1 below) are struck with hammers. The percussion can therefore also be used without a supply of wind to produce harp-like effects (of course, sounding rather "thin"). With wind operation of the first register, the percussion can increase the speed of the sound response of the tongues (especially in the bass); it also makes staccato and trill playing easier .

- Some art harmonies also contain an integrated celesta .

The registers of the Kunstharmonium are precisely defined. They are expressed by numerals in the relevant compositions or arrangements, as follows:

(1) Cor Anglais (English horn) 8 'in bass, flute (flute) 8' in treble; the main register ("basic game") with a direct, clear sound;

(2) Bourdon 16 'in bass, clarinet 16' in treble, with a round, soft sound;

(3) Clairon 4 'in bass, Fifre 4' in treble, with a nasal, powerful sound;

(4) Basson 8 'in the bass, Hautbois 8' in the treble, with a distinctive sound, as well as (3) in the rear area of the harmonium;

(5) Harpe éolienne (aeolian harp) 2 'in the bass, a floating register; Musette 16 'in treble, with a shawl-like sound;

(6) Voix céleste 16 'in treble, a floating voice for mystical effects;

(7) Baryton 32 'in the treble, a deep nasal voice, only available on larger instruments;

(8) Aeolian harp 8 'in treble, also only for larger instruments.

In general, in compositions for the artificial harmonium, the voices are notated at the pitch in which they are intended to be played, not in which they sound. An apparently high-lying melody with designation (2) sounds an octave lower, since a 16 'register is required. (When playing on a harmonium or an organ without 16 'you would have to transpose an octave down.)

Manufacturer

Art harmonies were produced by the following manufacturers:

- Victor Mustel, Paris: The company that invented the artificial harmonium and the term "harmonium d'artiste" (later "harmonium d'art"). Thus the instrument was often referred to simply as "Orgue Mustel", "Mustel Organ", "Mustel Organ" etc. Mustel also made combination instruments from artificial harmonium and celesta (orgue-célesta Mustel) with two and three manuals as well as two-manual "artificial harmoniums" and pedal harmoniums (even three-manual harmonium-celestas with pedal). While Mustel referred to all of his models as "art harmonies", according to today's terminology and the definition by Karg-Elert cited above, only the one-manual harmonies and the two-manual harmonium celestas are art harmonies in the true sense, but not the others ( experimental) models. From around 1913, the Mustel Kunstharmoniums had an extended disposition: In the bass, the Contrebasse 16 'registers (first around 1905, separately switchable lowest octave of Bourdon) and Basse 8' (separately switchable lowest octave of Cor anglais) built-in to be able to keep low notes in the prolongement (the prolongement only extends to the lowest octave), but at the same time to have the possibility of a different registration in the remaining bass half. The descant register Salicional 16 'has been found since around 1924 (the normally tuned reed rows of the floating voice Voix célèste as a "preliminary print"). From this time onwards, the Forte-Fixe register is not installed. Art harmonies with self-play equipment were sold under the brand name "Concertal", inexpensive models with less extensive disposition ("Spar-Kunstharmonie") and cheaper tongue material were sold under the name "Mustel-Studio". The models of all the other manufacturers listed here are more or less free copies of Mustel's model, without any of these manufacturers having significantly developed the artificial harmonium.

- Debain, Paris, built instruments with Mustel's double expression from 1859 (contract between Mustel and Debain on the rights of use of Mustel's double expression), although not with Mustel's art harmonium disposition

- Alexandre Père et fils, Paris. The art harmonies of this manufacturer - free copies of Mustel instruments - are called "Alexandre d'art".

- From 1904, Johannes Titz ( Löwenberg in Silesia ) produced detailed copies of one-manual Mustel art harmonies, initially in an identical case, later in a coarsened version of Mustel's Art Nouveau case, which Mustel built from 1910. From 1911, Titz's son-in-law Martin Schlag was involved in the manufacture of the art harmonium; after Titz's death in 1925, production from Schlag continued alone until 1945. Karg-Elert particularly valued the Titz harmonies.

- Mason & Hamlin, Boston (Style 1400). This model series was started in the 1880s. These are works imported from France (probably made by Mustel or Alexandre), which Mason & Hamlin installed in American-style cases. From 1904 there was a contract between Mustel and Mason & Hamlin for the production of art harmonies in America. So far, however, no instrument from this last production series has become known.

- Kaim & Fritsche, Kirchheim / Teck, "First German master harmonium factory"; The company was taken over by Schiedmayer on January 1st, 1905 and Gustav Fritsche became chief designer at Schiedmayer, where in future art harmonies were built according to the "Fritsche system".

- Schiedmayer, Stuttgart: Model name Dominator (also "Meisterharmonium Dominator") with and without Celesta. Schiedmayer expanded Mustel's standard disposition to include the registers [6] Violon 16 ', [7] Violoncello 8', [8] Undamaris 8 'in bass and [8] Aeolian harp 8', [9] Vox angelica 16 'in treble . As in the later Mustel instruments, extra registers for which only the lowest bass octave of some registers are switched on, so in Schiedmayer there are such "half-moves" as standard for registers [6], [5] and [2] in the bass. In addition to the conventional prolongation, Schiedmayer built a "prolongation piano", and in some models several individually switchable prolongations across the entire range of the keyboard. The "Scheola" model with self-play equipment is an equivalent of Mustel's "Concertal"

- Balthasar-Florence, Namur (artificial harmoniums with and without celesta, also single-manual harmonium celestas, where the celesta does not have its own manual, but can be connected to the harmonium manual). Arnold Schönberg temporarily owned a one-manual harmonium celesta by Balthasar-Florence.

- Victor Mazet, Brussels.

- Couty & Liné, Paris

- Couty & Richard (1867–1874), Paris (double expression according to their own system, like a Sourdine générale)

- J. Richard et Cie., Paris.

- Christophe & Etienne (modified Kunstharmonium disposition)

- Kasriel, Paris

- Petitqueux-Hilard, Bagnolet near Paris (also combination instruments with celesta)

- Charles-Henry Bildé, Annecy (modified Kunstharmonium disposition)

- Vitus Gevaert, Gent (modified double expression for two-manual harmonium)

- Teofil Kotykiewicz , Vienna

- Mannborg, Leipzig, (style 55, suction wind artificial harmonium) and so-called "normal artificial harmonies", d. H. Suction wind harmonies with the own keyboard range and double expression device for this type of instrument. "Normal art harmonies" are not art harmonies in the classical sense, as the art harmonium-specific literature can only be carried out to a limited extent due to the deviating range of the keyboard.

- Lindholm, Borna (model name "Imperial" as well as "Normal-Kunstharmonie").

- Hofberg, Leipzig (in France after the First World War under the manufacturer's pseudonym "Melodian"; Saugwind-Kunstharmonium)

- Hörügel, Leipzig ("Grandola Artist", suction wind artificial harmonium with modified artificial harmonium disposition).

- Hinkel, Ulm: Kunstharmoniums and so-called "Spar-Kunstharmonie" with double expression and reduced disposition.

- Ed. F. Köhler, Pretzsch (suction wind synthetic harmonium).

- Ölund & Almquist, Stockholm, suction wind art harmonium

The manufacturers built instruments with an artificial harmonium disposition (and an artificial harmonium-like disposition) but without double expression:

- Gilbert Bauer, London

- Cottino & Tailleur, Paris

- Hörügel, Leipzig, Hinkel, Ulm and others.

The Trayser company constructed a device (erroneously) called "Doppelexpression" (or "Double expression") for some of their instruments with a disposition that was not specific to the art harmonium. However, this is a simple wind swell without bass and treble division, which is structurally not included is related to Mustel's double expression.

literature

- Doris Baumert: The harmonium maker Johannes Titz in Löwenberg. (PDF)

- Friederike Beyer: The Art Harmonium. In: Christian Ahrens, Gregor Klinke (ed.): The harmonium in Germany. 2nd Edition. Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-923639-48-1 , pp. 133-159.

- Michel König: Arnold Schönbergs Herzgewächse op. 20. New insights into performance practice. In: Helmut C. Jacobs, Ralf Kaupenjohann (Ed.): Brennpunkte III. Essays, discussions, opinions and factual information on the subject of the accordion . Augemus Musikverlag, Bochum 2006, ISBN 3-924272-09-3 , pp. 78-93.

- J. Prévot: Mustel, facteurs et facture d'harmoniums d'art. In: Bulletin des Amis de l'Orgue. no. 304–305, Paris 2013, pp. 3–322.