lie detector

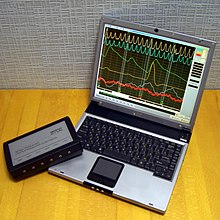

A polygraph is a device that continuously measures and records the course of physical parameters (namely the peripheral physiological variables) - such as blood pressure , pulse , respiration or the electrical conductivity of the skin - of a person during a survey. In professional circles, the device is not referred to as a lie detector, but as a polygraph ("prolific writer"), multi-channel writer or also a biosignal device . The term “lie detector” is incorrect because the polygraph is merely a technical aid with which physiopsychological parameters are measured and recorded. The recorded reactions are not specific to the truth or falsehood of the answer given, but merely indicate the current level of activation .

Development and history

The basic idea of the polygraph goes back to the psychologists Carl Gustav Jung and Max Wertheimer . At the beginning of the 20th century they published two independent papers on the use of physiopsychological procedures as indicators for legal issues. In March / April 1913, Vittorio Benussi constructed an apparatus at the University of Graz that registers the breathing phases and the pulse and from which it can be read whether the test subject is lying - the first polygraph. A polygraph was tested for the first time on February 2, 1935 in an experiment by Leonarde Keeler.

Since then, polygraphs have spread in some countries, but the main country of use was and is the USA, where the American Polygraph Association is also a lobby organization . The areas of application range from job interviews to police interrogations . Secret services such as the CIA and the Federal Police FBI in the USA also use polygraphs to assess the trustworthiness of current and potential employees.

In addition to polygraphs, alternative methods for recognizing true or false statements have recently been developed. These include purely voice-based ones, which use changes in the voice as an indicator of lies and can be used during a telephone conversation, as well as infrared cameras , with which the blood flow to the face is made visible and used as an indicator.

theory

Polygraphic research is based on the assumption that lying makes people at least slightly nervous. Even if this nervousness remains invisible to the other person, it generates involuntary reactions through the autonomic nervous system . This momentary level of activity of the organism can be registered and recorded using appropriate measuring devices.

Suitable reactions include:

- Change in breathing rate

- Change in heart rate

- Change in blood pressure

- electrodermal activity - change in skin resistance due to sweating

- Tremble

Several of these reactions are monitored simultaneously for a reliable assessment. The polygraph itself is nothing more than a measuring device that measures and records these very reactions. The device does not evaluate it and is the sole responsibility of the polygraphist who has been trained accordingly. A polygraphist should be able to distinguish real reactions from deliberately induced reactions.

Carrying out a polygraphic examination

There are two common polygraphic test procedures to clarify the truth of a statement, for example in the case of a suspicion of a crime : the factual knowledge test and the comparative question test.

Factual knowledge test

The factual knowledge test is an indirect method because the person to be examined is not asked directly whether he has done this or that, but is asked whether he knows something about the crime to be investigated. The aim is to find out whether he has knowledge of details of the crime that only the perpetrator can have. For this purpose, the person to be examined is first asked what he knows about the alleged act and where this knowledge comes from. Then he is asked six questions about a certain aspect of the act (manner of commission etc.), one of which is the appropriate alternative. It has been shown that the reactions are particularly high when the question is answered untruthfully in the negative to the applicable answer alternative. According to Max Steller , various laboratory studies even showed “that test subjects without factual knowledge could be identified 100 percent correctly using the factual knowledge test in almost all investigations, ie that no false-positive assignments were made. 80 to 95 percent of people with factual knowledge were classified correctly . "

Comparison question test

The comparison question test (also called control question test or CQT ) is not about possible factual knowledge, but the person to be investigated is asked directly about the facts to be clarified, for example whether he committed the crime to be investigated. Such a question can be, for example, on allegations of sexual coercion: "Have you ever kissed person X?" The questions aimed at the allegation (usually three) are referred to as questions of fact. They are related to (if possible four) comparison questions. The methodological approach on which the experimental set-up is based consists in comparing the reactions of one person to the questions related to the crime with the reactions of the same person to the comparison questions presented. The crime-related questions trigger a strong reaction from both the perpetrator and the falsely suspected person. In the case of the wrongly suspected, the comparison questions trigger even stronger reactions than the crime-related questions, while the perpetrator is not at all distracted from the threat that the crime-related questions pose to him. In order for the comparison questions to fulfill their purpose, they must be formulated in such a way that they “occupy” the test subject for the duration of the investigation, so that their conscientious answers “cause him trouble”. In order to achieve this, the comparative questions relate to socially disapproved behavior of the person examined, namely in the same normative area to which the acts of which he is suspected belong.

Initially, a conversation is held with the test subject, in which, in addition to a biographical anamnesis, the consumption of medication, alcohol and other drugs within the last 24 hours as well as the length of bedtime in the previous night are asked. Then the crime-related questions are discussed with the person to be examined and then the comparison questions. If both factual and comparative questions are established, the test subject is familiarized with the examination procedure and a test run is carried out with him. For this purpose, the test person is asked to select one of the numbers 22 to 26 and to note this number without the examiner being able to take notice. The subject is then connected to the polygraph, i. H. The measuring sensors are placed on him in the form of a blood pressure cuff on the left upper arm, a breathing belt on the chest, finger electrodes to measure the sweat secretion on the ring finger and on the index finger of the left hand, and a finger clamp with which the blood flow in the skin is measured over the fingertip. Then three individual tests are carried out: First, the numbers 22 to 26 are asked one after the other, whereby the test person should always answer “No”, even if he is asked for the number that he has noted. In the second round, the numbers are queried in a different order, with the respondent again always having to answer “no”. In the third round, the test person should answer the questions truthfully. The main purpose of the number test is to rule out disturbances that would make the evaluation of the reaction curves to be obtained in the main test impossible or unsafe. A side effect that increases the accuracy slightly is that the test subject is made clear about the reliability of the test. This happens when the examiner "reveals" the number noted by the examiner to the examinee. As a rule, the examiner already knows the noted number after the first two runs.

Then all the questions are read out to the test person again and it is explained to him that the test run was satisfactory and that there are no difficulties in the way of performing the actual test. Following this information, the person to be examined is asked if he would like to undergo the test. He is further told that if he does not want this, he need only say so. The examination would then be stopped immediately and he would not even be asked why he did not want to undergo the test. No negative conclusions should and would not be drawn from his rejection. If the subject decides to continue the test, the evaluation and explanation of the reaction curves are followed by the main investigation. The polygraph is usually used in three runs, but the measurements can also be made up to five times. The test evaluation then begins. The three introductory questions are not evaluated. They serve to "absorb" the effect known in psychology that the first stimulus presented in a series always receives increased attention.

During the evaluation, the reaction to the question related to the offense is compared with the reaction to one of the two adjacent comparison questions. For this purpose, the physical reactions recorded on graph paper (breathing, skin resistance, blood pressure and peripheral skin blood flow) that occurred during the three to five rounds of the main examination are evaluated. The different curve sizes are quantified using a seven-point scale. If a difference is not clearly recognizable, the rating “0” is given; if it is clearly recognizable, it is rated with "1", with a large difference with "2" and with an extraordinarily large difference with "3". If the reaction to the crime-related question is greater, the number is given a minus sign; if the reaction to the comparison question is stronger, a plus is awarded. The seven-point scale therefore ranges from −3 to +3. If the content of the crime-related questions is different, an overall value can be calculated for each individual question by adding up all the comparison values determined for the relevant crime-related question, taking into account the sign. The sum is then the test value for the relevant crime-related question. In experimental research and in criminal practice, the following limit values have proven effective: Values of +3 and above are indicators that the question related to the crime was answered truthfully in the negative. Values from −2 to +2 do not allow any reliable conclusion. Finally, with values of −3 and below it can be assumed that the question related to the crime was answered untruthfully in the negative.

If the three crime-related questions evaluated have the same content (i.e. only differ in the formulations), then all comparison values can be added up to a total value for the entire test, taking into account the sign. With this constellation, the following limit values have proven themselves in experimental research and in criminal practice: Values of +6 and above are indicators for the truthful negation of the crime-related questions, values from −5 to +5 do not allow a reliable conclusion, and values of −6 and below, it can be assumed that the questions related to the offense were answered untruthfully in the negative.

Criticism of lie detectors

In view of the fact that polygraph recognition can cause great damage if it is unreliable, the dissenting voices are numerous. It is argued that there is no scientifically tenable proof of reliability, but that many cases of misjudgments by lie detector tests are known and the tests can be demonstrated to be manipulated.

Legal assessment

With its judgment of February 16, 1954, the Federal Court of Justice forbids the use of lie detectors both in criminal proceedings and in preliminary investigations, even if the accused consents to their use. This results from Art. 1 Abs. 1 GG as well as § 136a StPO . Admissibility does not depend on the usefulness, correctness and reliability of the polygraph ("lie detector"), but solely on the principles governing criminal proceedings. These would prohibit the use of the device.

The test violates human dignity because the accused is a participant and not the subject of the proceedings. The truth may have to be clarified by the court without the involvement of the accused.

“These principles of constitutional and criminal procedural law are rooted in the fact that even the suspect and offender are always confronted with the whole as a responsible, moral personality; in the case of proven guilt he may and must be bowed to atonement under the violated law; his personality, however, must not be sacrificed beyond those legal restrictions to the certainly important public concern of combating crime. "

The polygraph ("lie detector") continues to impair the will of the accused and undermines the freedom of will guaranteed in Section 136a of the Code of Criminal Procedure (prohibition of abuse).

“The aim of the polygraph is to obtain more and different“ statements ”from the accused than during the usual interrogation, including those that he makes involuntarily and cannot make without the device. In addition to the conscious and willful answer to the questions, the unconscious also "answers" without the accused being able to prevent it. Such an insight into the soul of the accused and their unconscious impulses violates the freedom of decision-making and exercise of will ( § 136a StPO) and is inadmissible in criminal proceedings. In order to maintain and develop one's personality, there is a vital and indispensable emotional space that must remain untouched in criminal proceedings. "

On December 17, 1998, the Federal Court of Justice again rejected the polygraph as evidence because of the lack of reliability of the results. However, he contradicts the reasoning of the judgment of February 16, 1954 and sees no violation of human dignity with the consent of the person concerned. A violation of Section 136a (1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure was also not recognizable, since the person concerned was not deceived. The Federal Court of Justice also reacted negatively in its decision of November 30, 2010.

On May 14, 2013, the Dresden Higher Regional Court ruled that the "investigation with a polygraph [...] in custody and access law proceedings [is] a suitable means of exonerating an innocent person (...)"

On March 26, 2013, the Bautzen District Court decided that the exonerating result of a polygraphic examination (prepared in a family court dispute) can also be used as an exonerating circumstantial fact in criminal proceedings.

On July 31, 2014, the Federal Administrative Court declared in a ruling that a polygraphy test carried out in judicial disciplinary proceedings is unsuitable evidence (BVerwG, ruling of July 31, 2014, Az .: 2 B20.14, ZBR 2014, 420 ff.). The judges criticized the fact that in family court decisions in which the result of a polygraphic examination was considered usable, the OLG Dresden and the AG Bautzen did not sufficiently comment on the question of a fixed connection between a certain expressive behavior and specific reaction patterns of the autonomic nervous system.

On October 17, 2017, the Bautzen District Court (lay judge's court) acquitted a defendant who denied an allegation of abuse and had exonerated himself by means of a polygraphic examination. In its decision, the court also dealt with the criticism of the Federal Administrative Court and rejected it: “Without giving further reasons for its objection, the BVerwG is denying something that even the Federal Court of Justice no longer doubts. In essence, the Federal Administrative Court questions the existence of a fixed connection between a certain testimony and specific reaction patterns of the autonomic nervous system (BVerwG loc. "(AG Bautzen, judgment of October 26, 2017 - 42 Ds 610 Js 411/15 jug, BeckRS 2017, 138202).

Lack of scientific basis

A first major point of criticism relates to the theory on which the use of technology is based, namely the assumption that the technical aid of a polygraph test ("lie detector") can record and evaluate physical reactions during a survey in such a way that the truth of Answers can be "measured". The measured differences in excitation are, however, basically unspecific, i. H. It is not possible to tell from the change in arousal itself whether it was triggered by a sense of guilt, stress when lying or the fear of being falsely suspected. 'Lie detectors' do not measure lies, but only changes in physical excitement that can be traced back to nervousness or other emotions. This means that someone who does not react calmly to a question is at risk of being taken for a liar despite a truthful answer. Emotional responses from an innocent suspect to haunted accusations are not surprising, especially if the respondent is close to the crime victim.

A second point of criticism relates to the empirical evidence with which the hit rates of the polygraph should be proven. This evidence comes either from the laboratory or from the field; There are serious methodological problems with both data sources. In laboratory studies, it is nearly impossible to recreate the stress a person experiences when questioned in a real investigative process. This is especially true for the arousal of falsely suspects. Therefore, in the laboratory, it is often possible to separate liars and truthfully testifying persons on the basis of arousal, but the test situation is not sufficiently realistic. In field studies, the suspect's confession is used as the criterion for the actual perpetration (with which the polygraph result is related). The fact that a suspect decides to make a (possibly even false) confession is in turn not independent of the polygraph result. The confession is therefore not a suitable comparison criterion.

Bias through prejudice

One of the characteristics of lie detectors is that they do not output exact numbers or the like. The results depend on the interpretation by the examiner, although the same recording can be evaluated differently by different polygraphists. This means that prejudices cannot be ruled out.

In the so-called friendly polygraph examiner hypothesis, an interaction between the measurement result and the attitude of the examiner is assumed in such a way that a friendly examiner would achieve relieving results, be it that the suspect is less afraid of discovery and the measurable differences in excitation would be lower as a result or that the examiner would rate the results as relieving.

Proponents of “lie detectors” point out that the results of an EKG machine are basically of a similar nature to those of a polygraph (a curve recorded on paper), but an EKG is said to be a scientifically tenable method. The difference between polygraph and EKG is that the basics of the EKG results are completely clear (electrical voltage of the various heart muscles ); and that the same damage to the heart also leads to the same results. This lack of reproducibility leads to a leeway for interpretation that encourages prejudices.

Manipulability

It is possible to generate measurable responses at will through methods that the investigator does not discover. In this way, the result of a test can be steered in a desired direction and possibly another person can be charged with a crime. This happens not only through self-hypnosis for the critical questions, but by increasing arousal for the control questions. Leading polygraphists claim they can detect any kind of such manipulation, but fail to prove it. What is certain is that members of special military units (as part of their RtI = Resistance-to-Interrogation training phase) and employees of secret services have long been trained in manipulating lie detector tests.

Known cases of unsuccessful lie detector tests

There have been many known cases where reliance on polygraphs has caused harm.

Aldrich Ames was a CIA employee who sold classified information to the Soviet Union . Above all, it concerned the identities of sources in the KGB and the Soviet military who supplied the US with information. As a result, at least 100 covert operations were exposed and at least ten informants were executed. Ames passed two polygraph tests at the CIA while he was spying and was only discovered by the FBI involved. As he later said, he had asked his Soviet contact what he should do before the tests. He was told to just relax on the tests, which he then did.

Melvin Foster was subjected to a polygraph test as a suspect in the Green River murders in 1982 , which he failed. As a result, he continued to be publicly suspected for years despite the lack of solid evidence. It wasn't until 2001 that he was finally cleared of all suspicions, when DNA tests linked Gary Ridgway to the cases. Ridgway was initially a prime suspect, but then went unnoticed as he passed two polygraph tests. Ridgway was able to continue his series of murders and finally confessed to 49 murders to date.

Brain scans as a lie detector

New methods try to determine the truth of a statement using brain scans. Using fMRI recordings that make active areas of the brain visible, companies such as B. Cephos have achieved hit rates of 90%. The basic idea is that lying is a more complex process than telling the truth; as a result, more or other brain areas ( frontal and parietal lobes ) are active. Another reason is: the lie puts more strain on the brain than the truth and therefore certain regions are supplied with more blood. However, if the test person thinks about what he is going to say beforehand and "persuades" himself firmly enough that it is true, then the prepared answer from memory ( temporal lobe or hippocampus ) is queried during the test and thus appears to be true.

The Berlin neuroscientist John-Dylan Haynes is working on a lie detector that is said to be “infallible and independent of subjective assessments”. The starting point of the considerations for the development of a "brain scanner", a "neural lie detector" is that a brain stores previously experienced situations as "neural mirror images", recognizes them and makes this clear, even if the person tries to hide the knowledge about it: the brain activity a person betray the subject. The idea is that the brains of Islamist terrorists will react when pictures of terror camps are played to them; On the same basis - so the idea - it will be possible to convict suspected criminals of a certain crime if one shows them pictures of crime scenes: even if the perpetrator denied involvement in the crime, his brain would recognize him if he was among the simulated crime scene situations which relates to the criminal offense of which he is rightly accused. Compared to the pretended crime scene situations, in which it was not involved and therefore has not stored a neural mirror image, the brain would react recognizably to the crime scene situation experienced, even if the perpetrator wanted to hide it. The brain’s recognition of the crime scene cannot be deliberately influenced.

See also

literature

- Daniel Effer-Uhe: Possible uses of the polygraph - the misleadingly so-called “lie detector”. In: Marburg Law Review. 2013, pp. 99-104.

- Matthias Gamer, Gerhard Vossel: Psychophysiological statement assessment : Current status and newer developments. In: Journal of Neuropsychology. 20 (3) 2009, pp. 207-218. doi : 10.1024 / 1016-264X.20.3.207

- Holm Putzke, Jörg Scheinfeld, Gisela Klein; Udo Undeutsch : Polygraphic examinations in criminal proceedings: News on the factual validity and normative admissibility of the expert evidence introduced by the accused. In: Journal for the entire field of criminal law. 121, 2009, pp. 607-644. doi : 10.1515 / ZSTW.2009.607

- Hans-Georg Rill: Forensic Psychophysiology: A contribution to the psychological and physiological foundations of newer approaches to "lie detection" . Johannes Gutenberg University , Mainz 2001. urn : nbn: de: hebis: 77-1914 ( dissertation )

- Forensic Psychology Section in the Professional Association of German Psychologists (Ed.): Psychophysiological statement assessment. In: Practice of Legal Psychology. 9, 1999. (special issue)

Web links

- The Federal Court of Justice generally excludes polygraphic examination methods as evidence in judicial proceedings

- Committed to the “truth” , new lie detector combines thermal images with facial expression analyzes, Fanny Jimenez, April 2, 2012

- Entry in Skeptic's Dictionary , English

- American Polygraph Association , English

- AntiPolygraph.org , Critical Review and In- Depth Guide to Passing Polygraph Tests , English

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lafayette Model 76056 Polygraph. In: German Spy Museum. Retrieved January 16, 2020 (German).

- ↑ a b c "Invention of the lie detector - dishonest skin" , commented photo series by Katja Iken on one day , February 3, 2015

- ↑ See Holm Putzke, Jörg Scheinfeld, Gisela Klein, Udo Undeutsch: Polygraphic investigations in criminal proceedings. News on the factual validity and normative admissibility of the expert evidence introduced by the accused . In: Journal for the entire field of criminal law. 121, 2009, pp. 604-644.

- ↑ Max Steller : Psychophysiological investigation of perpetrators ("lie detection", "polygraphy"). In: M. Steller, R. Volbert (Ed.): Psychology in criminal proceedings. Huber, Bern 1997, p. 92.

- ↑ Description of the test procedure according to: Holm Putzke, Jörg Scheinfeld, Gisela Klein, Udo Undeutsch: Polygraphic investigations in criminal proceedings. News on the factual validity and normative admissibility of the expert evidence introduced by the accused . In: Journal for the entire field of criminal law. 121, 2009, pp. 604-644.

- ^ BGH judgment of February 16, 1954, Az. 1 StR 578/53, BGHSt 5, 332 ff.

- ^ BGH judgment of February 16, 1954, Az. 1 StR 578/53, BGHSt 5, 332, 333.

- ^ BGH judgment of February 16, 1954, Az. 1 StR 578/53, BGHSt 5, 332, 334.

- ^ BGH judgment of February 16, 1954, Az. 1 StR 578/53, BGHSt 5, 332, 335.

- ↑ The Federal Court of Justice followed the critical opinion in its decision. (All reports and judgments in: Praxis der Rechtsspsychologie. 9, 1999 (special issue Psychophysiological Assessment of Statements)); Press release Federal Court of Justice No. 96 of December 17, 1998 .

- ^ BGH decision of November 30, 2010, Az. 1 StR 509/10.

- ↑ cf. also the discussion of the BGH decision of November 30, 2010, Az. 1 StR 509/10 (including a description of the legal history) by Holm Putzke in the journal for legal studies . (ZJS) 06/2011, 557 (PDF file; 106 kB)

- ↑ OLG Dresden, decision of May 14, 2013, Az. 21 UF 787/12, BeckRS 2013, 16540.

- ^ AG Bautzen, judgment of March 26, 2013, Az. 40 Ls 330 Js 6351/12, BeckRS 2013, 08655.

- ↑ Peter Kurz: Lie Detector - Guilt or Innocence on graph paper WZ Westdeutsche Zeitung of November 10, 2017

- ^ Sächsische Zeitung: In case of doubt for the polygrafen Sächsische Zeitung of October 27, 2017

- ↑ Dietmar Hipp and Steffen Winter: Answers of the Unconscious Der Spiegel 44/2017, pp. 26/27

- ↑ M. Steller, K.-P. Dahle, K.-P .: Scientific report: Basics, methods and application problems of psychophysiological statement and perpetrator assessment ("polygraphy", "lie detection"). In: Practice of Legal Psychology. 9, 1999, special issue, pp. 178-179.

- ^ Brain Scans May Be Used As Lie Detectors ( Memento from September 6, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) . AP / ABC News, Jan. 28, 2006.

- ↑ Red web in the convolutions of the brain - A Californian company has developed a lie scanner . In: Berliner Zeitung. 13./14. October 2007.

- ↑ A look into the brain: topic on the program “Enigmatic Mimik”. ( Memento from January 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive )