LM function

The LM function , also called LM equation or LM curve , is an economic model of macroeconomics . It represents the equilibrium condition of money supply and money demand in the money and financial markets and is derived from equating the money supply and money demand functions.

The LM function, together with the IS-LM model, was the leading textbook model for decades. The model has been criticized since the turn of the millennium because the central banks no longer pay attention to the money supply. Today a Keynesian consensus model is being discussed, in which the central bank does not control the money supply, but determines the interest rate according to the Taylor rule .

term

The designation LM function is old more than 50 years, with the "L" for "liquidity preference" ( liquidity preference is) and "M" for "money supply" ( money supply is). The LM function says that the interest must adjust itself in equilibrium in such a way that, with a given income, the amount of money that corresponds to the amount of the given, interest-independent money supply M is demanded. In the literature, the term LM curve is often used as a synonym. Sometimes, however, a distinction is also made between the LM function as a condition of equilibrium and the LM curve as the resulting curve of the combinations of interest and national income .

The LM function is of particular economic importance because, together with the IS function, it forms the IS-LM model . This model assumes that the central bank pursues a monetary policy by determining the money supply, which then results in the equilibrium interest rate - but because the central bank can change the money supply at any time and can also react to a changing money demand, the equilibrium interest rate becomes determined at all times by the decisions of the Central Bank.

The analytical derivative of the LM function

The demand for money

The money demand Md (d stands for demand) of the entire economy is the aggregated money demand of economic agents . Therefore, the demand for money in the economy as a whole depends on the amount of transactions that take place in an economy and on the level of the interest rate . In order to define the number of transactions, it is assumed that this is proportional to the nominal income. Formulated in an equation, this means that the demand for money corresponds to the product of the nominal income PY and the function of the interest rate L (i). This means:

The minus sign indicates that when the interest rate rises, the preference for liquidity and thus the demand for money decreases, since economic agents prefer to invest their money at high interest rates. Consequently, the demand for money rises when the interest rate falls, since investing - as an alternative to saving - no longer brings sufficient profit. The demand for money thus depends negatively on the interest rate. There is also a connection between money demand (Md) and nominal income (PY). The nominal income corresponds to the income in euros. If the nominal income rises, the economic agents can carry out more transactions . Simply put: more income - more expenses. The amount of transactions and the level of the interest rate determine the demand for money for the economy as a whole. It can be assumed that the demand for money increases proportionally to the nominal income.

The money supply

In order to explain the derivation of the money supply Ms, it should be noted that in reality there are two providers of money. The commercial banks provide sight deposits, while the central bank provides cash and sight deposits with the central bank. For reasons of simplification, however, it is assumed when determining the amount of money that the economic entities only have cash. That is, it is believed that only the central bank offers money. From this it follows that the amount of money supply is controlled by the central bank and is therefore given exogenously. The money supply M determined by the central bank then corresponds to the money supply Ms. That means:

The derived LM function

By equating the money demand and money supply functions ( ), the following equation results, which is called the LM function:

All combinations of money demand, nominal income and interest rate are shown, which create a balance for a given money supply.

LM curve

The LM curve is the expression of the equilibrium in the money and financial markets. It describes all possible combinations of interest i and national income Y in which the money market is in equilibrium. The LM curve (“money demand equals money supply curve”) therefore represents all combinations of income and interest in which there is a balance between money demand and money supply on the money market.

Graphical derivation of the LM curve

The LM curve can be derived graphically with the help of the 4-quadrant scheme based on specified behavior. The holding of money is taken into account and the demand for money is divided into different components according to the different behavioral motives (especially with Keynes):

So the demand depends on:

- from the transaction register - the amount of money required for consumption (transaction or sales motive),

- from the precautionary fund - the amount of money that is held in order to be able to make unforeseen payments (precautionary motive), as well as

- from the speculative fund - the amount of money that is set aside for securities trading (speculative motive).

In the graphic representation, however, the demand for the precautionary fund is not treated separately, but rather it is assumed that this is integrated into the function of the transaction fund - due to the same structure of the demand functions. The demand of the speculative till is shown in the upper left quadrant, then the equilibrium condition L = M in the lower right quadrant and the demand of the transaction till in the lower left quadrant. The LM curve in the upper right quadrant can then be derived from these graphically as shown in the figure.

Areas of the LM curve

The LM curve can be divided into three different areas:

1. "Keynesian area" or liquidity trap

The horizontal part of the LM curve is referred to as the "keyness area" or liquidity trap. In this area the LM curve is completely interest-elastic, which is why this is of no importance in practice, in contrast to the theoretical consideration.

2. Intermediate range or normal range

The area of the LM curve that has a non-linear shape is referred to as the intermediate area or normal area. In this range, the interest elasticity is between zero and infinity. Please note that this is often shown linearly for reasons of simplicity.

3. Classic area

In the classic area of the LM curve, the interest elasticity is zero. From a graphical point of view, this is the vertical part of the curve.

The essential connections of the LM function

The LM curve can be used to represent and describe two essential relationships of the LM function:

- A decrease or increase in nominal income for a given amount of money leads to a decrease or increase in the interest rate.

- The decrease or increase in the money supply causes the equilibrium interest rate to rise or fall.

If the nominal income changes, this affects the interest rate. As nominal income rises, the number of transactions carried out in the economy increases. This leads to an increase in the demand for money. The money demand curve shifts to the right, which increases the equilibrium interest rate. These relationships are shown graphically in Figure 1.

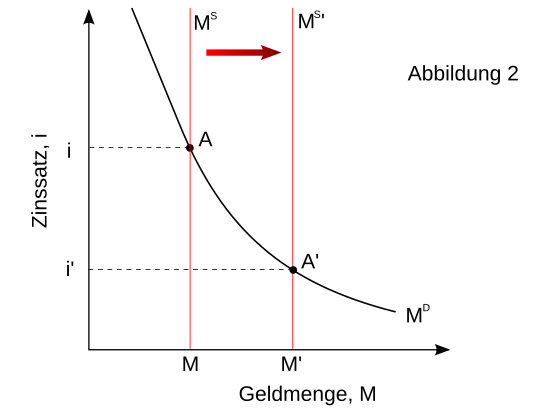

In Figure 2, the effects of a change in the money supply are shown. If the central bank increases the money supply, this leads to a shift in the money supply curve to the right. The money supply M increases. Since the interest rate has to adjust itself in equilibrium so that the money supply and money demand match, the interest rate falls. Consequently, a decrease in the money supply leads to a shift in the money supply curve to the left, the money supply decreases, the interest rate increases.

See also

literature

- Ulrich Baßeler u. a .: Fundamentals and problems of the national economy. Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-7910-2437-0 .

- Wyplosz Burda: Macroeconomics. A European text. 4th edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-19-926496-1 . (German translation: Michael C. Burda and Charles Wyplosz: Macroeconomics: A European perspective. 2nd edition. Vahlen, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-8006-2856-2 ).

- Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics. Pearson, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8273-7363-2 .

- Konrad A. Hillebrand: Elementary Macroeconomics. Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-25792-7 .

- Sigurd Klatt: Introduction to Macroeconomics. Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-486-21289-3 .

- Hans-Peter Nissen: Introduction to Macroeconomic Theory. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-7908-0474-6 .

- Klaus Rittenbruch: Macroeconomics. Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-486-25486-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Blanchard, Illing: Macroeconomics. Pearson, Munich 2004, p. 849

- ↑ David Romer: Keynesian Macroeconomics without the LM Curve (PDF; 184 kB)

- ↑ Lambsdorff / Engelen: The Keynesian consensus model (PDF; 642 kB)

- ↑ Farewell to the LM curve ( memento of the original from November 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Cf. Blanchard, Illing: Makroökonomie. Pearson, Munich 2004, p. 109

- ↑ Cf. Blanchard, Illing: Macroeconomics. Pearson, Munich 2007, p. 109

- ↑ Cf. Blanchard, Illing: Macroeconomics. Pearson, Munich 2007, pp. 109-110

- ↑ Cf. Blanchard, Illing: Macroeconomics. Pearson, Munich 2007, p. 111

- ↑ See Klatt: Introduction to Macroeconomics. Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, p. 58

- ↑ Cf. Nissen: Introduction to the macroeconomic theory. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg 1999, p. 168

- ↑ See Rittenbruch: Macroeconomics. Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, page 246

- ↑ See Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson, Munich 2004, p. 110 .

- ↑ See Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson, Munich 2004, p. 111 .