Leipzig Fatherland Association

The Leipzig Fatherland Association was established shortly before the outbreak of the March Revolution on March 28, 1848. It was banned again after the revolution on August 21, 1849 after 18 months. During this time most of the local and national state associations were formed.

prehistory

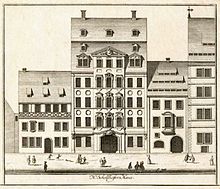

Many politically like-minded people met at the Schützenhaus in Leipzig . At first they met disguised as a “bowling society” and celebrated important historical and political days of remembrance. Later on there were political meetings and political speeches, but mainly Robert Blum attracted the masses.

From these meetings in the rifle house, Blum founded a "Speech Practice Club" in 1848, apart from Blum, this club was headed by Arnold Ruge , Heinrich Wuttke , Carl Eduard Cramer and the later head of the "Saxon Fatherland Club " Wilhelm Heinrich Bertling . The speech practice club, which was always threatened by the police and the authorities, wanted to be more than a discussion club. The opposition members who were active in leading positions in the revolution in 1848 came together in the speech practice club.

Blum's political activity in Leipzig now turned mainly to the speech practice association in order to gain a rallying point for his party and to train talented speakers for better times. When the old system began to falter in February, it was especially Blum who worked on the overthrow of the Ministry. In these decisive days he was very active, active everywhere. His first concern was founding a political association and a newspaper.

history

On March 28, 1848, the "Leipziger Vaterlandsverein" was founded and the forbidden Fatherland Papers were continued in April. A direct line led from the speech practice association to the organization of the petty-bourgeois democracy in Saxony in 1848, to the fatherland association.

Well-known party leaders of the radicals took over the leadership of the Fatherland Association: Robert Blum, Rudolph Rüder , W. Bertling, C. Ed. Cramer, H. Wuttke, Eduard Theodor Jäkel , Robert Friese a . a. m. At a general assembly held in Leipzig on April 23, 1848, the Fatherland Association set up its program:

- “The purpose of the German Fatherland Association is to work for the

unity, freedom and prosperity of the German people and the German fatherland.

To this end, he strives to awaken and uplift:

General education, love and enthusiasm for the German fatherland; Sense of legal freedom, of equal entitlement and obligation, of fraternal cooperation of all.

He recognizes the only guarantee for the attainment and preservation of these goods:

a Basic Law for the entire German fatherland, which establishes as the highest principle:

the constitutionally expressed will of the German people is the highest law; The representatives of this popular will are the freely elected representatives of German tribes, united in a German Reichstag. The German Fatherland Association recognizes the right of the individual states:

free choice of their form of government. In Saxony he wants to work with the people:

maintenance and modern training of the constitutional monarchy, as a representative and executor of the people's will. "

In a book with the title "Leipzigs Wühler und Wühlerinnen", in which the term Wühler is equated with revolutionary, one can find the names of all members of the fatherland associations.

In order to understand the situation in the Saxon Fatherland Associations, it is necessary to take a look at their development since the spring of 1848. Since the end of April the republican tendency has become more and more noticeable both outside and inside the fatherland associations.

Against the resistance of the circle around Wuttke, an application was made to the Leipzig Fatherland Association at the end of May to change the moderate association program and to include the demands of the Republicans. Although the Republicans were obviously in the majority, Wuttke, as chairman of the Leipzig Fatherland Association, knew how to postpone the change in the association's program in the republican sense.

The strength of the republican tendencies in the club had made it clear to Wuttke and the other anti-republicans that they were becoming more and more isolated. This right-wing group tried all the harder to enforce its anti-democratic line in the association. Wuttke did not shy away from a dishonest concealment of his views: on July 8, as a member of the “German Association”, he signed an address of no confidence to the Frankfurt Left, and on July 10, a declaration of confidence to the Saxon MPs of the Left. Such behavior had to provoke the republican opposition in the Fatherland Association to decisive action.

At the general assembly of the Saxon Fatherland Associations on July 9th and 10th in Dresden , the differences between the republicans and the anti-democratic wing were barely evened out. The question of the republic should only be discussed in the individual associations. As the decision on the political position of the Fatherland Associations was once again left open, the General Assembly also postponed the question of whether a union with the “German Association” or the “Republican Association” should take place.

But such compromises could not stop the necessary differentiation process. In view of the intensification of the class struggle in the summer of 1848, which required decisions, the fronts also had to be clarified in the Saxon Fatherland Associations. This was also necessary because Wuttke made repeated attempts to force the Republicans out of the club. The Democrats could not stand idly by Wuttke's striving for a liberal “metamorphosis” of the club. At a meeting of the Leipzig Association on July 18, they demanded his resignation. Wuttke replied that on August 2nd, together with part of the committee, in violation of the statutes, he decided to dissolve the association. He then reconstituted the club without the Republicans. But the Republicans declared on August 3rd, led by Eduard Theodor Jäkel and Arnold Ruge, that the association had not been dissolved. By contrast, the committee practically excluded itself from the association through its dissolution resolution. A new committee was elected, made up of only Republicans. Jäkel became the provisional chairman.

On August 3, the Leipzig Fatherland Association split into two associations, the constitutionally moderate "German Fatherland Association" with chairmen Bertling, Vieweg, Cramer, Christoph as secretary and the democratic "Republican Fatherland Association" with Ruge and Jäkel. Wuttke resigned from the Fatherland Association on August 23.

After the split it became apparent that the Republicans were gaining more and more support in the Saxon Fatherland Associations. Numerous associations in the larger cities, whose representatives in Dresden had still voted against the republicans, now declared themselves in favor of the republican direction. Thus the moderate associations, which still had adherents mainly in the countryside, became more and more of the hopeless minority. The Republican Democratic trend received a strong boost.

Blum's death on November 9, 1848 triggered major protests in all German states and led to a rapprochement between the two fatherland associations in his adopted home, which drew up common electoral lists for the Saxon state elections.

" Der Leuchtthurm " reported in January 1849: The elections in Saxony can already be described as happy. The determined party of patriotic associations has triumphed in most districts, and we can expect a popular chamber for the first time. As a result of the elections, both clubs have reunited and set up a joint program.

After the revolution of 1848/1849 was suppressed, the Saxon Fatherland Associations were banned by government decree on August 21, 1849.

literature

- Chronicle of the City of Leipzig 1851, pages 221 and 251.

- Memorandum for the German Fatherland Associations of Saxony.

- "Der Leuchtthurm" weekly for entertainment and instruction for the German people. 1848

- “The present.” An encyclopedic representation of the latest contemporary history for all stands. Page 615

- "Dresdner Journal" Herold for Saxon and German interests.

- A negotiation by the German Fatherland Association in Leipzig at the meeting on May 30, 1848.

- Supplementary conversation lexicon. Fourth volume in fifty-two numbers of the supplementary sheets to all conversation lexicons. Published by an association of scholars, artists and specialists under the editorship of Dr. Ms. Steger.

- History of the October days in Vienna. Described and documented by Fenner von Fenneberg.

- German parliamentarism during the revolutionary period: 1848–1850. Manfred Botzenhart. Droste-Verlag, 1977 - 886 pages. Page 331, 332, 355, 379.

- German general newspaper. 1848. Editor A. Kaiser. Printing and publishing by F. a. Brockhaus in Leipzig.

Web links

- Political parties in Germany 1848–1850

- Franz Ulrich Nordhausen: Leipzig's diggers, daguerreotypes and club figures . Self-published, 1849.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Supplementary volumes to the Conversationslexikon first volume. Regensburg 1849. page 180.

- ^ The present, an encyclopedic representation of the latest contemporary history for all stands, fifth volume. Leipzig Brockhaus 1850. page 604.

- ↑ Supplementary Conversation Lexicon. Fourth volume, Leipzig 1849 p. 327.

- ^ Robert Blum from the Leipzig Liberal on the Martyr of German Democracy. Weimar 1971, page 102.

- ↑ Supplementary Conversation Lexicon. Fourth volume in twenty-two numbers of the supplementary sheets for all conversation lexicons. 1849. page 451.

- ↑ Leipzig's diggers. From Franz Ulrich. In self-publishing. Nordhausen 1849. Printed by Fr. Thiele.

- ^ German parliamentarism during the revolutionary period: 1848–1850. Manfred Botzenhart, Droste-Verlag, 1977 - page 331ff.

- ^ Robert Blum from the Leipzig Liberal on the Martyr of German Democracy. Weimar 1971, page 201.

- ^ Chronicle of the City of Leipzig, A Handbook of the History of Leipzig, by Eduard Sparfeld, Leipzig 1851, printed by Friedrich Andrä, pages 221 and 251.

- ^ Friedrich Gerstäcker - Life and Work: Biography of a Restless Man, Thomas Ostwald, Friedrich Gerstäcker Society, 2007, page 91.