Market equilibrium with monopoly competition

The determination of the market equilibrium in monopoly competition presupposes that not only the demand function and the supply function are equated and thus the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity are determined, but also the number of suppliers in equilibrium are taken into account.

Assumptions

The basic assumption is that each supplier will sell more the more the demand increases and the higher the prices of the competitors are. Furthermore, if the offer price of the individual provider rises in a market segment with increasing providers, the lower the sales of the individual company will be. The following demand function for the products or services of a provider can be derived from this:

With

- : Quantity requested from the provider

- : the total market demand

- : the number of providers in this market segment

- the segment's own offer price

- or the average price of the segment

- with : substitution coefficient that indicates the industry-specific sales change as a result of price changes.

With this function, we can already see that the market share of the individual providers can only be the same if, given the demand, all providers would offer the same offer price on the market. You can even derive further insights: Provides a provider below the market average price on , it will get a bigger share of the market and is a supplier to fix a price higher than the average price of the market , he will get a smaller share of the market.

In order to obtain further results , symmetry must be assumed for the providers for the model developed by Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld . Symmetry means: “that their demand and cost functions are identical for all companies (even if they produce and sell slightly different products)”.

The following is intended to demonstrate that there is a link between the number of providers in a market segment and the average total costs in a segment as well as between the number of providers and the offer price.

Derivation

Linking the number of companies and the average cost of a company

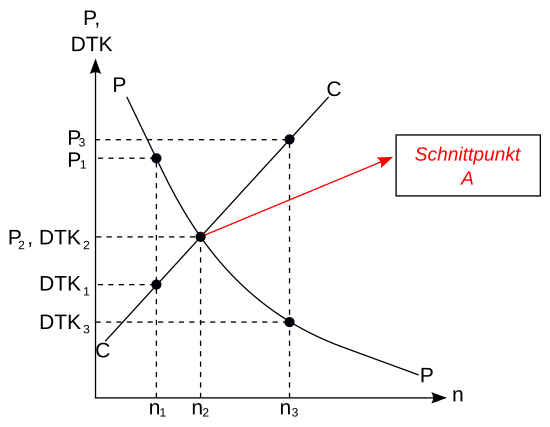

This link is illustrated in the following figure. Classically, here too - as with other market models - the permanent market or segment equilibrium lies at the intersection of the CC and PP functions.

The CC function is increasing, as shown below. An increase in fixed costs means a turn up to the left, whereas an increase in the demand of the entire market y results in a turn down to the right. An increase in marginal costs c leads to a parallel shift to the top left.

The PP function is a falling function (see below), which is detached from the overall market demand and therefore does not result in any shifts. Influencing variables on the PP function are, on the one hand, the marginal costs , which cause a parallel shift to the top right and the industry-specific sales changes ( ) as a result, a turn to the bottom left results.

The typical reactions of the individual providers can also be derived until the equilibrium is reached. Individual providers will leave the market segment if the market price is less than their total average cost (loss). On the other hand, other providers will enter the market if the market price is above the average total costs (profit).

In the further formation of the model for the formation of a market equilibrium in the case of monopolistic competition, the prerequisites should continue to apply that the providers have falling average total costs. Assuming a linear supply function, the variable in would have to have a negative value ( ). It is also a condition that all providers are synchronized (symmetrically), so at the intersection of the PP curve with the CC curve, all providers will have the same offer price. The market share (sales) of the individual providers corresponds to the product and the segment demand . The sales volume of the individual providers also regulates the average total costs of the provider ( fixed cost degression ). If the market share increases (i.e. the quantity produced and sold), the average total costs decrease. This is the evidence needed to prove the relationship between the number of segment providers and the average total costs, which can be described in the following function:

With

- equivalent to marginal costs (and in the case of a linear cost function: variable unit costs )

- Fixed costs

The large number of segment providers correlates positively with the providers' average total costs . The more providers operate in a segment, the more the average total costs increase, and there is no fixed cost degression. In the figure this function or this proof is shown with the CC function.

Linking the number of companies and the offer prices of a company

Experience shows that the link between the number of segment providers and the offer price is given in such a way that additional providers in the market lead to falling prices. From this we derive a linear market demand for the form for the provider , from which the marginal revenue results as .

The modeled market demand reflects the theory that the offer price is viewed by all segment providers as an invariable quantity. The providers of the segment then react as if they could not apply to the price of the other providers. The segment demand can then be described as follows:

The part in brackets is defined as a fixed cost and can be interpreted as a rise in the market demand curve. The marginal revenue is determined using the following evidence scheme in 8 steps:

- Change after

- Establishing the revenue function

- Determine the proceeds for

- Exclude

-

by replacing

- with a marginal change in quantity tends towards zero

- Determination of the absolute change in quantity

- Determination of the marginal change in quantity

Finally, the derived formulas for marginal costs and marginal revenues are equated to determine the market equilibrium:

In order to establish the desired connection between the number of companies and the offer price, the above equilibrium condition is resolved according to :

Using the context , this can be further simplified to:

The offer price of the segment providers correlates negatively with the number of segment providers. If more and more providers force their way into the market segment, the offer price of the respective provider drops. In the illustration s. o. this function is removed with PP.

interpretation

It can be stated that the offer price that a provider sets and the average total costs are related to the number of providers in the respective market segment.

In the longer term, the market equilibrium will change as shown in the illustration on p. o. in the point , d. H. at the intersection of the CC function and the PP function.

If one now looks at the illustration s. o. more precisely, conclusions can be drawn about the market. If there are providers in the market segment, the average total costs and the offer price are above the point . The difference between the amount of the total average costs is the profits that the segment providers realize. These profits will arouse the interest of other producers over a longer period of time and new providers will enter the market under the premise of free market access. The asking price will decrease and the average total cost will increase. For this reason, we are approaching the point with , there are the average total cost equal to the price . For the provider, this means that no profits are realized. If starting from . Enter more providers in the market, the total average costs will exceed the price, for example, applies to : . In this situation, the providers suffer losses equal to the difference . Some providers will therefore leave this market segment again and the remaining providers will reduce their supply volume, so that there is a tendency towards equilibrium. Only the situation in the point with providers is stable in the long term .

Changes as the market expands

The model developed and explained above can be expanded to include foreign trade. The international economic relations (trade) with other countries increase the sales market. This means that it becomes larger and the CC function turns to the bottom right (see Figure 2). This effect with the involvement of foreign countries is only given if no new providers enter the market. This allows a new CC function to be derived, whereby the new market equilibrium in this segment will become the point of intersection . The price and the average total cost will fall.

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Krugman / Obstfeld (2006): Internationale Wirtschaft, 7th edition, Munich: Pearson, p. 168.

- ↑ Krugman / Obstfeld (2006): Internationale Wirtschaft, 7th edition, Munich: Pearson, p. 169.

literature

- Krugman / Obstfeld (2006): International Economy. 7th edition, Munich: Pearson.

- Bofinger, Peter (2003): Fundamentals of Economics. 4th edition, Munich: Pearson.

- Kneips, Günter (2008): Competitive Economy , 3rd Edition, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

- Lehmann, Gerhard (1956): Market Forms and Monopoly Policy , Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

- Woll, Arthur (1993): General Economics. 11th edition, Munich: Vahlen.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (2001): Fundamentals of Economics. 2nd edition, Stuttgart: Schäffer-Poeschel.

![{\ displaystyle y_ {i} = y \ cdot \ left [{\ frac {1} {n}} - b \ cdot (p_ {i} -p) \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0893529814a72ca486af95b94bd71ef3ab4d4933)

![{\ displaystyle \ left [y_ {i} = {\ frac {1} {n}} \ cdot y \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6b74aa40902a7f602a29c4cb09c2fe45e238c6f9)

![{\ displaystyle y_ {i} = \ left [{\ frac {y} {n}} + y \ cdot b \ cdot p \ right] -y \ cdot b \ cdot p_ {i}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/de1b713ee9790934c4fae007bf49d44a0f9f0d79)

![{\ displaystyle E = \ left [{\ frac {a} {b}} - {\ frac {1} {b}} \ cdot y_ {i} \ right] \ cdot y_ {i}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aac323557f9946512161ef06101f2075bd442c0)

![{\ displaystyle \ left [y_ {i} + dy_ {i} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c948b81d4f44525748f4ab11cd028c90f15a0554)

![{\ displaystyle E (y_ {i} + dy_ {i}) = P_ {i} \ cdot \ left [y_ {i} + dy_ {i} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/20464d9861fdfe695663ea90ace43c045b6f1568)

![{\ displaystyle E '= \ left [{\ frac {a} {b}} - {\ frac {1} {b}} \ cdot (y_ {i} + dy_ {i}) \ right] \ cdot \ left [y_ {i} + dy_ {i} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/26765ce65c5b197f644b59bdbdd022bb906b2ab1)

![{\ displaystyle E '= \ left [{\ frac {a} {b}} - {\ frac {1} {b}} \ cdot y_ {i} - {\ frac {1} {b}} \ cdot dy_ {i} \ right] \ cdot \ left [y_ {i} + dy_ {i} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6db9c8e7230723c684d5c25e9f64960c9d86a671)