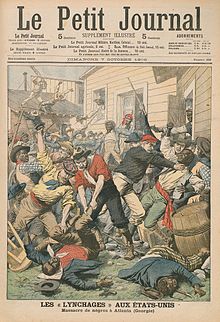

Atlanta massacre

The massacre of Atlanta , in English also known as "1906 Atlanta Race Riot," was the attack of an armed white mobs on African-American citizens in Atlanta from 22 to 24 September 1906. In the event that the so-called racial unrest in United States is counted, 35 people were killed.

prehistory

Atlanta was known in the southern states in 1906 for its comparatively progressive relationships between the "races" , that is, between whites and African-Americans . In the post- Reconstruction phase , it was one of the few places in the region to see economic and population growth. The population grew by more than 60% from 1900 to 1910, with a good third of the residents being Afro-American, and eleven major railway lines used the city as a distribution center. In that decade, only Los Angeles saw a major economic boom. In addition to the geographically favorable location between the east coast and the Tennessee Valley, the economic and ethnic concept of the “New South” that dominates Atlanta was the basis for this development . This envisaged that the agrarian southern states, which were still weakened by the consequences of the civil war, should be economically strengthened through the creation of urban industrial, logistics and trade centers. In this model, the role of ordinary workers was foreseen for the African Americans, thereby improving their economic situation and calming tensions between whites and blacks. On the other hand remained by the classification of African Americans in the lower hierarchical level of the working people white supremacy ( "white supremacy") maintained. As a result, a black middle class emerged in Atlanta despite the Jim Crow legislation in the southern states. In addition to self-employed business owners along Auburn Avenue, their relatives were mainly employed as servants in hotels, restaurants, department stores and private households as well as workers at the freight yards. Atlanta also had the world's largest concentration of higher education institutions for blacks, with WEB Du Bois and John Hope teaching among others . Civil rights activist Booker T. Washington had a large following among African-Americans , while his black opponents in Atlanta published The Voice of the Negro , considered the most sophisticated of its kind in America. For these reasons, many Atlanteans saw the problematic relations between African Americans and whites in their city as resolved. Nonetheless, with crime, prostitution and gambling, which were virulent in certain districts, the frequently observed side effects of rapidly growing cities, which were intensified by conflicts between the “races”.

On September 20, 1906, Democrat and former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan performed in Atlanta, drawing several thousand visitors to the city. At a subsequent banquet in his honor, the Fulton County's sheriff informed Governor Joseph M. Terrell of the alleged attack by a black man on a white woman, which rumored to have spread to Atlanta and led to the formation of lynch mobs . The newspapers fueled the tense mood with sensational reports on September 21. On the same day, a new rumor spread in Atlanta that a drunk African American had broken into the home of a white family the previous night. At the same time, that Friday, the police were patrolling the city's saloons , which were segregated for blacks, and arrested several people there. By noon the atmosphere was tense and many white teenagers and young men flocked downtown . At 4:00 p.m. the newspaper boys distributed a special edition of the Atlanta Journal , which reported on a milk merchant's wife who narrowly escaped an attack by an African American. Soon after, a separate edition of the Evening News appeared, and an hour later another, each dealing with another attack of this type. The newspaper boys were particularly busy that day and positioned themselves at train stations, hotels and restaurants, where they sold the papers hundreds of times and called out “Second Attack” and “Third Attack”. These false, sensational newspaper reports were then the immediate trigger for the massacre. The underlying motive for violence, however, was the restoration of white hegemony and black servility within the framework of a society in the southern states, which was characterized by racism and segregation.

procedure

Several thousand whites gathered near the Georgia State Capitol in the early evening of September 22nd . The destructive rage of the mob was directed first against businesses of the Afro-Americans and then against them themselves, with black employees being searched for in train stations, freight yards, trams and hotels. In the course of this, the 5th Georgia Infantry Regiment was mobilized to stop the violence but also to prevent the blacks' self-defense measures. In the end, according to historian David F. Krugler, the massacre left 35 dead, 32 of whom were African American. The information officially announced at the time amounted to twelve dead, including two white people, while unofficial estimates put the number of victims at over 50.

literature

- Mark Bauerlein: Atlanta (Georgia) Riot of 1906. In Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton (Eds.): Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. Greenwood, Westport 2007, ISBN 0-313-33300-9 , pp. 15-24.

- Rebecca Burns: Rage in the Gate City: The Story of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. 2nd, revised edition. University of Georgia Press, Athens 2006, ISBN 0-8203-3307-7 .

- David Fort Godshalk: Veiled Visions: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of American Race Relations. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2005, ISBN 0-8078-2962-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mark Bauerlein: Atlanta (Georgia) Riot of 1906. In Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton (Eds.): Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. 2007, pp. 15-24; here: p. 15f.

- ↑ Mark Bauerlein: Atlanta (Georgia) Riot of 1906. In Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton (Eds.): Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. 2007, pp. 15-24; here: p. 19f.

- ↑ David F. Krugler: 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back Cambridge University Press, New York 2015, ISBN 978-1-107-06179-8 , p. 13.

-

↑ Mark Bauerlein: Atlanta (Georgia) Riot of 1906. In Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton (Eds.): Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. 2007, pp. 15-24; here: p. 15.

David F. Krugler: 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back Cambridge University Press, New York 2015, ISBN 978-1-107-06179-8 , p. 13.