Midnight talks

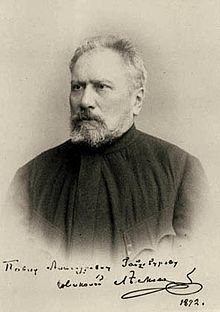

Midnight Talks ( Russian Полунощники , Polunoschtschniki ) is a short story by the Russian writer Nikolai Leskov , which was completed in the fall of 1890 and was published in the November and December 1891 issue of Westnik Evropy in Saint Petersburg . Other magazines, for example Russkaya Mysl , had refused to publish this satire on the Russian clergy .

Three women

Ajitschka

The first-person narrator goes ashore after the crossing and spends the night with other people waiting in a hotel. Like the people waiting, he hopes for an audience with the seer . Perhaps the seer, this saint , can alleviate his tribulation and anxiety. He cannot sleep, and through the thin walls of the hotel room he becomes an ear-witness of two dialogue sequences from his room neighbors. The elderly couple on the right apparently soon fall asleep after their brief conversation. The two ladies on the left, however, exchange ideas in a rambling manner. From the conversation it can be seen that the elder, a certain Marja Martynovna, guides the younger - Raissa Ignatjewna, known as Ajitschka - to the healer. Ajitschka would donate her wealth to the seer if he could arrange for her prayers to be answered. Her lover should finally take her to wife. Ajitschka wants to enter the port of marriage, unlike her loved one, wants children. The reader does not find out how this ends. Because the first-person narrator has heard enough: The seer - presumably a charlatan - has his questionable visionary potency rewarded with cash. The first-person narrator puts the money for the overnight stay on the table and runs off.

Klavdiya

Almost nothing more than the narrative text frame has been sketched above. Leskov's actual narrative concern, concerning true religiosity , is deposited in the figure of Klawdija Rodionovna.

The widow Marja Martynovna, employed by Ajitschka as a partner, is the slut in the story. The cunning woman, a nasty slanderer, would even commit contract murder for Ajitschka if necessary.

The intriguer Maria Martynovna had been dismissed from the house of the excellent manufacturer Stepenev before she hired Ayichka. Margarita Mikhailovna, mistress of the Stepenev family, had commissioned Marya Martynovna with an extremely delicate mission. Margarita Mikhailovna's daughter Klawdija had become engaged to the wrong man. The seer should talk the daughter out of marriage to this man. The gossip base Maria Martynovna was supposed to get the audience through. She did it. However, the seer had lost out in his insistent conversation. Klavdia's Christianity - based on the teachings of Tolstoy - was no match for the miracle worker.

Marja

Since the first-person narrator - that listener on the wall - sees nothing but only hears the conversations, the humorist Leskow weaves into Marja Martynovna's verbatim speech. The simple trick makes it easier to distinguish the speaker between the half-educated Marja and her dialogue partner, the educated Ajitschka.

reception

- 1892: On the one hand, contemporary Russian literary criticism attested to the author's artistic talent and praised the deep inner truth of the text, but on the other hand, unanimously rejected the aforementioned distortions of Marja's language as excessive, even as making the reader sick.

- 1959: Sechkareff writes that Leskov hated the prophet and miracle worker Johannes von Kronstadt, who was close to the Russian government, but was not allowed to give his name out of consideration for Russian censorship.

- 1973: Reissner comments on Leskov's response to the Mannerism accusation of his language on the part of contemporary literary critics.

literature

German-language editions

Output used:

- Midnight talks. German by Georg Schwarz. P. 34–153 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The valley of tears. 587 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1973 (1st edition)

Secondary literature

- Vsevolod Sechkareff : NS Leskov. His life and his work. 170 pages. Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1959

Web links

- The text

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

- Entries in WorldCat

Remarks

- ^ The place of the action is Kronstadt on the island of Kotlin (Setschkareff, p. 148, 14th Zvu).

- ↑ More precisely: The establishment described as a hotel is the private house called Ashidazija (from Russian ажиотаж (aschiotasch) - Run and Russian ожидать (oschidat) - wait ).

- ↑ The seer was John of Kronstadt - an archenemy Leskov and Tolstoy meant (Reissner in the postscript output used, S. 559, last paragraph). Otherwise Leskov writes mostly it when the seer is meant (for example, see pages 110 and 111 in the used edition). Sometimes the local (edition used, p. 76, 13th Zvu) is also mentioned in this context .

- ↑ With Klawdija Leskow drew a picture of a niece of the rich Russian railroad king Savva Wassiljewitsch Morosow (Russian Морозов, Савва Васильевич ) (Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 559, 1st Zvu).

- ↑ Marja's verbatim speech teems with such "slip of the tongue". A few examples from this (the reference in the notation (chapter, page in the edition used) in round brackets): Pompon for Coupon (4.60), Schürzennöter for Schürzenjäger / Schwerenöter (4.62), Huckenotten for Die Huguenots (5, 70) Grandezvous for Rendezvous (6.80), Glühquot for Cliquot (6.86), Parisianer for Persianer (6.86), Kummer salad for lobster salad (6.91), carbine for Kabardiner (8,108) and euro Peter for Europeans (14,143).

Individual evidence

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 558 below

- ↑ Edition used, p. 135, 11. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 115, 11. Zvu

- ↑ Edition used, p. 150 middle

- ↑ Setschkareff, p. 149 below

- ↑ Russian criticism

- ↑ Setschkareff, p. 148, 19. Zvu to p. 151, 1. Zvo

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 560 below