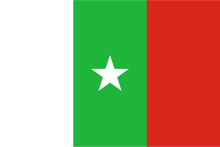

Mouvement des democratiques de la Casamance forces

The Mouvement des forces démocratiques de la Casamance (MFDC for short; French: "Movement of the Democratic Forces of Casamance") was a political group which, according to its own understanding, campaigned for the rights of the residents of Casamance in southern Senegal . Climatically, the rainier and more fertile Casamance and the much drier north of Senegal differ significantly, so that the Casamance produced agricultural surpluses in peacetime, which represented an important part of the food supply of all of Senegal.

Ethnic background

The MFDC claimed to speak for all residents of Casamance and presented itself as a regionally based, multi-ethnic movement. The program, symbolism and area of operation of the MFDC showed a strong reference to the Diola ethnic group . Whether the MFDC was composed exclusively of members of the Diola ethnic group was controversial. A one-sided religious foundation of the identity of the MFDC could, however, be ruled out, as important functionaries of the MFDC had both Muslim and Catholic religious affiliation.

Amnesty International pointed out in 1999, on the occasion of the MFDC's fire raids on the city of Ziguinchor, that the human rights organization had for years condemned the MFDC's unpunished abuses against unarmed civilians, heads of traditional communities or people who had moved to other parts of Senegal and who they were under suspected of collaborating with the Senegalese government. Dozens of citizens, including women and children, were victims of ill-treatment, torture and arbitrary killings. Some of these acts appeared to have been committed by the MFDC on the basis of ethnic criteria. Members of the Manjak, Mandingo, Balante and Mancagne ethnic groups were often targeted by the MFDC because they believed that these ethnic groups would not join the struggle for Casamance independence.

Within Senegal, the Diola form a minority of 6% of the population who are concentrated in the Casamance, a region separated from the rest of the state by the state of Gambia .

Organizational structure

Organizationally, the MFDC consists of three pillars: the domestic organization, the foreign organization and the Atika as the armed arm. The influence of the domestic leadership, formally provided with the highest decision-making authority, eroded in the course of time in favor of the foreign organization and in particular in favor of the armed arm. Diamancoune Senghor, who as General Secretary held the highest formal office of the MFDC , was never able to get his way with his appeals to the fighters to respect the ceasefire agreement . In the course of its history, the MFDC was continuously characterized by fragmentation and internal, sometimes armed, conflicts.

Little is known about the foreign organization.

The armed arm (Atika) was established in 1985. The military training was taken over by Casamancais (residents of the Casamance) who had previously served in the French army . The bulk of the fighters, along with these veterans, were formed by young men from the region.

history

Efforts to achieve autonomy and independence had existed for a long time when tensions between the Diola and the central government in Dakar increased at the beginning of the 1980s . The MFDC organized demonstrations and protest marches, whereupon the Senegalese government ordered the arrest of the political leadership of the MFDC in 1982. However, this only resulted in a further escalation of the situation, which ultimately resulted in the armed Casamance conflict .

There have been armed incidents since 1983; however, the situation worsened dramatically in 1990 when the MFDC received Guinea-Bissau's support . The MFDC mainly attacked military bases, while the Senegalese army attacked the separatist strongholds, especially in the Ziguinchor region in the west of Casamance , but also attacked supply bases in neighboring Guinea-Bissau. Hundreds of civilians were killed in the fighting and thousands more fled the region to the north or to Gambia and Guinea-Bissau. In the course of the 1990s, ceasefire agreements were repeatedly signed, but none of them lasted very long. The conflict came into the public eye in particular when four French tourists fell victim to the fighting; both sides accused each other of being responsible for the crime.

The MFDC was founded in 1982 at the instigation of Mamadou Sané and the Catholic priest Abbé Augustin Diamacoune Senghor . It first appeared publicly in December of the same year during a demonstration against the Senegalese government. The year 1983 was marked by two symbolically important attacks by the security forces, which contributed to a radicalization of the movement. From 1985 onwards, following instructions from the political leadership of the MFDC, the armed arm of the MFDC (Atika = Diola for "warrior") was set up under the direction of Sidi Badji.

Only five years after its founding did the Atika appear in 1990 with armed operations against Senegalese security forces. The Atika split into Front North and Front South in 1992 because the Front South, in agreement with Diamancoune Senghor, did not accept a peace agreement that Sidi Badji had negotiated with Dakar in 1991 (Cacheu Agreement).

The split deepened in 1993 through differing assessments of another ceasefire agreement with the Senegalese government. The North Front was much more powerful at the beginning and was able to establish itself for a long time in areas around Bignona on the border with Gambia. Over the years, both Front Nord and Front Sud found themselves exposed to further internal processes of division, which, particularly in the latter, prevented the institutionalization of a powerful structure. For a long time it was very difficult to describe the organizational structures of the MFDC-Atika due to the constant processes of division and frequent internal battles. The Senegalese government often found it difficult to identify those people who could speak credibly for the entire organization in peace negotiations.

In addition to the fighting against the Senegalese security forces and other factions of the Atika, fighters from the Sud Front were also actively involved in fighting during the political turmoil in Guinea-Bissau at the end of the 1990s, during which they intervened on the side of General Ansumané Mané .

Hope for a lasting peace solution was repeatedly disappointed by the failure of the various ceasefire agreements in the 1990s. Not least thanks to the flow of arms from Guinea-Bissau in favor of the MFDC, the conflict between the Front Sud and the security forces intensified towards the end of 1997/1998. As a result, despite another ceasefire signed in 1997, around 500 people were killed in the fighting in the period up to 2001 . In March 2001, Senghor wanted to put an end to this with another agreement with Dakar. In particular, the regulation provided for the clearance of mines, the return of refugees and the exchange of prisoners without granting the Casamance autonomy.

Various factions of the Atika rejected this regulation. Meanwhile, Jean-Marie François Biagui succeeded Senghor as General Secretary of the MFDC. Biagui also advocated a negotiated solution and called a meeting of the MFDC on October 6, 2003 in the city of Ziguinchor , which, however, was boycotted by the hardliners. This could not prevent the way to the formal peace treaty, which was signed on December 30, 2004 between Senegalese interior minister Ousmane Ngom and Diamacoune Senghor, now honorary chairman of the MFDC. Despite the actual political conflict being resolved, fighting and armed robberies continued to be reported from the Casamance, although their political character was difficult to assess.

Diamacoune Senghore died on January 15, 2007 in Paris.

Individual evidence

- ^ Bruno Sonko (2004): The Casamance Conflict: A Forgotten Civil War? In: CODESRIA Bulletin, Issue 3 + 4, pp. 30-34.

- ^ Joseph Glaise (1990): Casamance: la contestation continue. In: Politique africaine, No. 37, pp. 83-89.

- ↑ a b c d Martin Evans (2004): Africa Program Briefing Paper 04/2002. Armed Non-State Actors Project. Senegal: Mouvement des Forces Democratique de la Casamance. ( Memento of February 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Felix Gerdes (2006): Rule and Rebellion in the Casamance. In: Bakonyji, Jutta et al. (Ed.): Regulations of violence by armed groups. Baden-Baden: Nomos. Pp. 85-98.

- ↑ Amnesty International, June 29, 1999: Senegal: Casamance civilians shelled by the Mouvement des forces démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC)

- ↑ a b c Alexander Meckelburg (2006): Senegal (Casamance). In: Schreiber, Wolfgang; Working group on the causes of war research (ed.): The war events 2005. Data and tendencies of wars and armed conflicts. Wiesbaden: VS. Pp. 203-206.

- ^ A b Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Research and Analytical Papers, London. African Research Group: The Casamance Conflict 1982 - 1999 ( Memento of March 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (January 3, 2008)