National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association ( NAWSA ) was an organization founded on February 18, 1890 to promote women's suffrage in the United States. It was created through the merger of the two existing women's associations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which began at around 7,000, gradually increased to two million, making it the largest volunteer organization in the United States. She played a key role in the adoption and ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution (the so-called 19th Amendment), which has guaranteed women's suffrage since 1920.

Susan B. Anthony , a long-term leader in the women's rights movement, was the dominant figure in the newly formed NAWSA. Carrie Chapman Catt , who became president after Anthony's retirement in 1900, instituted the strategy of attracting wealthy members of the rapidly growing women's club movement whose money and experience could help build the women's movement. In Anna Howard Shaw's tenure as president, which began in 1904, it experienced a large increase in membership and growing public support.

After the Senate resolutely rejected the proposed "amendment" to women's suffrage (the necessary amendment to the United States Constitution) in 1887, the movement made most of its efforts in state campaigns for women to vote. Alice Paul joined NAWSA in 1910 and played a major role in the renewed interest in the national amendment. After continuing disputes with the NAWSA board of directors over the tactics of action, Paul created a rival organization, the National Woman's Party , which once again split the movement.

When Catt became president in 1915, NAWSA adopted its plan to centralize the federation and focus work on the Women's Suffrage Amendment as its primary goal. It did so in spite of opposition from the Southern Associations, who believed that a federal amendment would diminish state rights. Due to its large membership and the increasing number of female voters in states where women's suffrage had already been achieved, the MAWSA began to operate more as a “pressure group” than as an educational association. She gained additional sympathy for the cause of women's suffrage by actively helping in the war effort during World War I. On February 14, 1920, several months before the end of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, it transformed into the League of Women Voters , which is active to this day.

prehistory

The desire for women's suffrage in the United States sparked controversy even among women activists in the early days of the movement. In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention , the first conference on women's rights, passed a resolution in favor of women's suffrage only after lively debate. By the time of the National Women's Rights Conventions of the 1850s, the situation had changed and women's suffrage had become a preeminent goal of the movement. Three women’s movement leaders of the time played a prominent role in founding NAWSA many years later: Lucy Stone , Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony .

Shortly after the Civil War , in 1866, the eleventh National Women's Rights Convention was transformed into the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), which campaigned for equal rights for both African-American and white women, especially the right to vote. The AERA essentially disbanded in 1869, in part because of disagreements over the proposed 15th Amendment , which allowed African-American men to vote. Women leaders were disappointed that it did not also bring elections to women. Stanton and Anthony opposed ratification unless it was accompanied by another amendment giving women the right to vote.

Stone supported the amendment. She believed that its enforcement would spur politicians to support a similar amendment for women. She said the right to vote is more important for women than for men of color. But she said:

"I will be thankful in my soul if any body can get out of the terrible pit."

(English: "I am deeply grateful if '' any '' someone can get out of this terrible hole.")

In May 1869, two months after those bitter debates that turned out to be the end of the AERA meetings, Anthony, Stanton, and their allies formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was founded by Lucy Stone , her husband Henry Browne Blackwell , Julia Ward Howe, and their supporters, many of whom had helped found the New England Woman Suffrage Association. That happened a year earlier and was a sign of the looming split. The bitter rivalry between the two organizations created a climate of partisanship that lasted for decades.

Even after the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, differences remained between the two organizations. The AWSA worked almost entirely for women's suffrage, while the NWSA had a wide range of goals, including reforming divorce laws and equal pay for women. The AWSA had both men and women on its governing bodies, while the NWSA was led by women. The AWSA sought the right to vote primarily at the state level, while the NSWA focused more on the state level. The AWSA cultivated its image of respectability, while the NWSA sometimes used confrontational tactics. Anthony, for example, interrupted the official ceremonies to mark the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence to present the NWSA's Declaration of Rights for Women. Anthony was arrested in 1872 for voting, which was still illegal for women, and found guilty in a very high-profile trial.

Progress in enforcing women's suffrage was small after the split, but advancement in other areas strengthened the foundations of the women's movement. By 1890 tens of thousands of women were attending colleges and universities, a few decades earlier this had not been possible at all. The public no longer supported the idea of the “female sphere” so strongly that a woman should have a place in her home and that she should not interfere in political matters. The laws that allowed husbands to control their wives' activities had been significantly revised. And there has been a huge surge in all-female organizations seeking social reform. One example was the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the largest women's organization in the United States. In a powerful promotion of the women's suffrage movement, the WCTU supported this right to vote in the late 1870s on the grounds that women needed the choice to protect their families from alcohol abuse and other addictions.

Anthony increasingly began to emphasize women's suffrage more than other women's issues. Their goal was to unite the growing number of women's organizations who want to vote, even if they don't support the other women's rights demands. You and the NWSA began to put less emphasis on the confrontation actions than on the public image. The NWSA were no longer seen as an organization that disrupted traditional family structures by supporting, for example, what their opponents called "easy divorce". All of this had the effect of moving them closer to the direction of the AWSA. The Senate's rejection of the amendment proposed in 1887 on women's suffrage also brought the two associations closer together. For years the NWSA had endeavored to get Congress to put this proposed amendment to a vote. After resolving this by a total rejection, the NWSA began to put less energy into fighting at the national level; it moved more to the state level, as the AWSA was already doing. Stanton went on to promote and advance all aspects of women's rights. She advocated a coalition of radical groups, including social reformers, populists and socialists, who would support women's suffrage as part of a common list of demands. In a letter to a friend, Stanton said the NWSA

"has been growing politic and conservative for some time. Lucy [Stone] and Susan [Anthony] alike see suffrage only. They do not see woman's religious and social bondage, neither do the young women in either association, hence they may as well combine "

(German: (the NWSA) became political and conservative for a certain time, Lucy (Stone) and Susan (Anthony) both only see women's suffrage. They do not recognize the religious and social ties of women, as do the young women in all the clubs don't do, so they could join forces right away. ")

However, Stanton had largely withdrawn from the day-to-day work and toil of the suffrage movement. During this period she spent a lot of time with her daughter in England. Despite their differing views, Stanton and Anthony remained friends and worked together; they continued the togetherness that had begun in the early 1850s.

Stone devoted most of her life after the split to Woman's Journal , a weekly news paper she launched in 1879 to serve as the voice of the AWSA. By the 1880s, the Woman's Journal had expanded its circulation considerably and was seen as the news paper for the entire women's movement. The suffrage movement attracted younger members who were impatient with the ongoing split. They saw the different personalities as an obstacle rather than the differing principles. Alice Stone Blackwell , daughter of Lucy Stone, said:

"When I began to work for a union, the elders were not keen for it, on either side, but the younger women on both sides were. Nothing really stood in the way except the unpleasant feelings engendered during the long separation".

(German: When I started working for the association, the older ones weren't enthusiastic, on both sides, but the younger women on both sides were. In reality, nothing stood in the way except some uncomfortable feelings that formed during the long separation had.")

Merger of the rival clubs

Several attempts had been made to bring the two sides together, but without success. The situation changed in 1887 when Stone, nearing her 70th birthday and in poor health, looked for ways to overcome the split. In a letter to the suffragist Antoinette Brown Blackwell , she proposed the creation of an umbrella organization whose subdivisions should become the AWSA and NWSA. But the idea didn't get any supporters. In November 1887, the AWSA's annual conference passed a resolution asking Stone to speak to Anthony about the possibility of a merger. The resolution stated that the differences between the two associations "had been largely removed by the adoption of common principles and methods". (German: has largely disappeared through the adoption of common principles and methods) ". Stone forwarded the resolution to Anthony along with an invitation to a meeting.

Anthony and Rachel Foster , a young NWSA leader, traveled to Boston in December 1887 to meet with Stone. Stone was accompanied to the meeting by her daughter Alice Stone Blackwell , who was also on the board of directors of AWSA. Stanton wasn't there because she was in England. The meeting explored several aspects of a possible merger, including the name of the new association and its structure. Stone soon had concerns after telling a friend that she wished she had never proposed the merger, but the merging process slowly continued.

An early public sign of improving relations between the two associations was seen three months later at the founding convention of the International Council of Women organized and overseen by the NWSA in Washington - in conjunction with the 40th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention . It received friendly publicity, and delegates, from 53 women's organizations in nine countries, were invited to a reception at the White House. AWSA representatives were asked to sit on the podium with the NWSA representatives during the conference, which signaled a new atmosphere of collaboration.

The proposed merger did not cause any real controversy within the AWSA. The convening of the 1887 annual meeting, which also empowered Stone to explore the possibilities of the merger, did not even mention that it was on the agenda. The proposal was seen as a routine matter during Congress and was widely approved without debate.

The situation was different within the NWSA, where there was strong opposition from Matilda Joslyn Gage , Olympia Brown and others. Ida Husted Harper , Anthony's collaborator and biographer, said the meetings that the NWSA addressed this issue "were the most stormy in the history of the association." (Eng .: "the stormiest in the history of the association") Gage accused Anthony of having tactically weakened the opposition to the merger, and in 1890 formed a rival organization called the "Woman's National Liberal Union", but had no real success after that. The AWSA and NWSA committees had negotiated the terms of the merger, as the basis for an agreement in January 1889. In February Stone, Stanton, Anthony and other leaders from both associations issued an "Open Letter to the Women of America". Open Letter to the Women of America) declaring their intention to work together. When Anthony and Stone first discussed the possibility of a merger in 1887, Stone had suggested that the two of them, Stanton and Anthony, should not accept the presidency of the new combined organization. Anthony initially agreed, but other NWSA members strongly opposed it. The basis of the agreement did not contain such a definition.

The AWSA was originally the larger of the two organizations, but it had lost strength during the 1880s. The NWSA was seen as the main advocate of the women's suffrage movement, in part because Anthony had the ability to dramatically draw the attention of the national public. Anthony and Stanton had also published their extensive History of Woman Suffrage , which placed them at the center of the history of the women's movement and marginalized the role of Stone and the AWSA. Stone's public visibility had decreased significantly, in stark contrast to the attention she had received as a speaker on national lecture tours in her younger days. Anthony was increasingly perceived as a person of political importance. In 1890, there were prominent members of the House and Senate among the 200 people who attended their 70th birthday celebration, a national event held three days before the Congress that led to the unification of the two associations. Anthony and Stanton deliberately renewed their friendship at this event, frustrating opponents of the union who had hoped to play them off against each other.

Founding Congress

The "National American Woman Suffrage Association" (NAWSA) was established on February 18, 1890, by a convention that united the NWSA and the AWSA. The question of who would run the new organization was left to Congress delegates. AWSA's Stone was too sick to attend the convention and wasn't a candidate. Anthony and Stanton, both from the NWSA, each had their supporters.

The boards of AWSA and NWSA met beforehand to discuss their selection of presidential candidates for the unified association. At the AWSA meeting, Stone's husband Henry Browne Blackwell said that the NWSA had agreed not to meddle on minor matters (a concept involving Stanton) and to focus solely on women's suffrage (the concept of the AWSA, and increasingly, too by Anthony). The board recommended that the AWSA delegates vote for Anthony. During the NWSA meeting, Anthony urged that members vote for Stanton, not her, as Stanton's defeat would be viewed as an affront to their role in the movement.

The elections were held at the opening session of the Congress. Stanton received 131 votes for the presidency, Anthony 90 and two votes for others. Anthony was elected Vice President with a large majority of 213 votes, 9 votes for other candidates. As President, Stanton delivered the opening address to Congress. Urging the new organization to engage in a wide range of reforms, she said:

"When any principle or question is up for discussion, let us seize on it and show its connection, whether nearly or remotely, with woman's disfranchisement."

(German: If any principle or question is up for discussion, let's take it up and show its connection - whether narrow or broad - with the fact that women are not allowed to vote.)

She tabled controversial resolutions, including one calling for the participation of women at all levels of leadership within religious organizations and one describing liberal divorce laws as the "door of escape from bondage." Her speech, however, had no lasting effect on the organization, as most of the younger suffragists disagreed with her position.

Presidencies of Stanton and Anthony

Stanton's election as president was largely symbolic. Before the convention was over, she left for an extended stay with her daughter in England, leaving Anthony to lead. Stanton resigned the presidency in 1892, after which Anthony was elected to the position she had held practically from the start. Stone, who died in 1893, did not play a major role in NAWSA. The vitality of the women's movement declined in the years immediately after the merger. The new association was small; in 1893 it only had around 7,000 contributing members. He also suffered from organizational problems, such as having no clear idea of how many local women's rights clubs there were and who was on their board.

In 1893 NAWSA members May Wright Sewall , former Chair of the NWSA Executive Committee, and Rachel Foster Avery , NAWSA's Corresponding Secretary, played key roles in the World's Congress of Representative Women at the World's Columbian Exposition , which also became popular under the name "World's Fair in Chicago". Sewall presided and Avery was the secretary of the Organizing Committee for the Women's Congress.

In 1893, NAWSA voted on Anthony's objection to the decision to alternate the location of annual conventions between Washington and other parts of the country. Anthony's NWSA had always held their meetings in Washington prior to the merger in order to maintain the focus on the national women's suffrage amendment. Anthony expressed fear, as it later came about, that NAWSA would promote the state election to the detriment of national labor. NAWSA routinely did not create a fund for the work in Congress, which at that time consisted only of making statements on one day once a year.

Stanton's women 's Bible

Stanton's radical stance did not suit the new association. In 1895 she published The Woman's Bible , a controversial bestseller that deplored the use of the Bible in that it placed women in a subordinate status. Her opponents within NAWSA reacted sharply. They believed the book would harm the development for women's suffrage. Rachel Foster Avery, the association's correspondent secretary, strongly condemned Stanton's book in her annual report for the 1896 Congress. NAWSA voted to dismiss any association by the association with the book, despite Anthony's strong objection that such a move was unnecessary and hurtful.

The negative reaction to the book contributed to Stanton's influence in the women's suffrage movement declining, and it showed her increasing alienation from it. She did, however, send letters to every NAWSA convention, and Anthony insisted that they be read, even if their issues were controversial. Stanton died in 1902.

Southern strategy

Traditionally, the South had shown little interest in women's suffrage. When the proposed women's suffrage amendment was rejected by the Senate in 1887, it received no vote at all from southern senators. This indicated a problem for the future because it was almost impossible for an amendment to achieve ratification with the required number of states without at least some support from the South.

Henry Blackwell suggested a solution: to convince southern political leaders that they could secure white supremacy in their region by allowing educated women who were predominantly white to vote. Blackwell presented his plan to Mississippi politicians who were seriously considering it, a development that attracted the interest of many suffragists. Blackwell's ally in this endeavor was Laura Clay , who got NAWSA to campaign in the south based on Blackwell's strategy. Clay was one of several NAWSA members who opposed the proposed Women's Suffrage Amendment because it would encroach on state rights.

Suffrage groups were formed across the region amid predictions that the South would find its way to women's suffrage. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt (NAWSA's organization secretary), and Blackwell led the campaign in the South in 1895, the latter two calling for educated women only. With Anthony's hesitant collaboration, NAWSA maneuvered around to conform to the politics of white supremacy in the region. Anthony asked her old friend Frederick Douglass, a former slave, not to attend the 1895 NAWSA Convention in Atlanta, the first in a southern city. NAWSA black members were excluded from the 1903 meeting in the southern city of New Orleans. The NAWSA board of directors issued a statement during the event that said:

"The doctrine of State's rights is recognized in the national body, and each auxiliary State association arranges its own affairs in accordance with its own ideas and in harmony with the customs of its own section."

(German: "The principle of federal rights is recognized by the national body, and each sub-organization of the state regulates its own affairs in accordance with its own ideas and in harmony with the customs of its own areas.")

However, none of the southern states allowed women to vote as a result of this strategy, and most of the franchise organizations established in the south during this period fell into inactivity.

Catt's first presidency

Carrie Chapman Catt joined the suffrage movement in Iowa in the mid-1880s and soon became a part of the board of directors of the state women's suffrage association. Because she was married to a wealthy engineer who helped her in her suffrage work, she was able to devote much of her strength to the movement. In 1895 she was appointed chairman of the organizing committee, for which she raised money to send a team of 14 organizers into the field. In 1899 suffrage organizations were set up in every state.

When Anthony resigned as president of NAWSA in 1900, she succeeded in getting Catt, who had not been closely associated with either the NWSA or the AWSA before, to be her successor. However, Anthony remained an influential person in the organization until she died in 1906.

One of Catt's first steps as president was to introduce the Society Plan. This was a campaign to recruit wealthy members of the fast-growing women's club movement whose time, money, and experience could help build the women's suffrage movement. These clubs, which consisted mainly of middle-class women, were often involved in projects to improve social grievances. They generally avoided contentious matters, but women's suffrage was increasingly supported by their members. In 1914, women's suffrage was supported by the General Federation of Women's Clubs , the head organization of the club movement.

To make the movement of women's suffrage more attractive to middle and upper class women, NAWSA began popularizing a narrative of the movement that downplayed its members 'previous involvement in such controversial issues as racial equality, divorce reform, workers' rights, and criticism of religious communities. Stanton's role in the movement has been veiled over time, as have the roles of colored people and workers. Anthony, often treated as a dangerous fanatic in her younger days, was given a "grandmother" image and was venerated as a "saint of women's suffrage".

The reform energy of the so-called "Progressive Era" strengthened the electoral movement during this period. Beginning around 1900, this broad movement began at the lowest level with goals such as fighting corruption in government, preventing child labor, and protecting workers and consumers. Many of those involved saw women's suffrage as another goal of the drive for progress, and they believed that adding women to the electorate would help the movement achieve the other goals.

Catt resigned after four years, partly because of her husband's declining health and partly to help organize the International Woman Suffrage Alliance , which was founded in Berlin in 1904 in collaboration with NAWSA and with Catt as chairman.

Shaw's presidency

In 1904, Anna Howard Shaw , another Anthony sponsored woman, was elected president of NAWSA, who then served in that office for more years than any other person. Shaw was a hard worker and a talented public speaker. Her administrative and communication skills were nowhere near the same as those Catt was to demonstrate during her second term, but the association had brilliant successes under Shaw's leadership.

In 1906, with Blackwell's support, NAWSA members formed the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference. Although she openly had a racist program, she sought the support of NAWSA. Shaw denied this and set a limit on how far the organization would go to conform to southerners with their obviously racist views. Shaw said the organization would not accept rules that "mandated the exclusion of any race or class of people." (English: "advocated the exclusion of any race or class from the right of suffrage.") In 1907, Harriet Stanton Blatch , daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton , founded a rival organization called the "Equality League of Self-Supporting Women". This was partly due to the NAWSA's Society Plan, which was designed to attract women from the higher classes. It was later known as the Women's Political Union, whose membership relied on women workers from both business and industry. Blatch had recently returned to the United States after spending seven years in England, where she had participated in women's suffrage groups that were early to use militant tactics as part of their struggle. The Equality League gained a following by engaging in activities that many NAWSA members initially considered too daring, such as Suffrage Parades and Open Air Rallies. Blatch said of joining the women's movement in the United States:

"the only method suggested for furthering the cause was the slow process of education. We were told to organize, organize, organize, to the end of educating, educating, educating public opinion."

(German: "the only method to advance the matter was the slow process of education. We were told to organize, organize, organize, and in the end then education, education, formation of a public opinion.")

In 1908 the National College Equal Suffrage League was founded as a subsidiary of NAWSA. It had its beginnings in the "College Equal Suffrage League," which was founded in Boston in 1900 at a time when there were relatively many college students in NAWSA. It was established by Maud Wood Park , who later helped form similar groups in 30 states. Park later became an eminent leader in NAWSA.

In 1908, Catt was once again at the forefront of activity. She and her staff devised a detailed plan to unite the various women's rights groups in New York City (and later throughout the state) into an organization modeled on the "political machines" of the Tammany Hall model . In 1909 they founded the "Woman Suffrage Party" (WSP) during a congress that was formed by over a thousand delegates and other visitors. By 1910 the WSP had 20,000 members and a four-room headquarters. Shaw was not very comfortable with the WSP's independent initiatives, but Catt and the other leaders remained loyal to their parent organization, NAWSA.

Public opinion about women's suffrage improved dramatically during this period. The pursuit of women's suffrage was gradually becoming regarded as a worthy activity for middle-class women. By 1910, NAWSA's membership had skyrocketed to 117,000. NAWSA established its first permanent headquarters in New York City that year, previously operating mainly from the homes of its board members. Maud Wood Park, who had been in Europe for two years, received a letter that year from a staff member in the College Equal Suffrage League, who described the new atmosphere as follows:

"The movement which when we got into it had about as much energy as a dying kitten, is now a big, virile, threatening thing" and is "actually fashionable now".

(German: "The movement that had as much energy as a dying kitten when we got into it is now a big, masculine, scary thing and it's very fashionable right now")

The shift in public perception was reflected in state efforts to achieve women's suffrage. In 1896 only four states, all in the west, allowed women to vote. There were six state campaigns for women to vote between 1896 and 1910, and all of them failed. The turning point came in 1910 when Washington state achieved women's suffrage, followed by California in 1911, Oregon, Kansas and Arizona in 1912, and more.

In 1912, WEB Du Bois , president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), publicly lamented NAWSA's reluctance to accept black women. The association responded in a friendly manner by inviting him to speak at the next congress and distributing his speech in print. Nevertheless, NAWSA continued to minimize the role of black suffragists. It accepted some black women as members and some black clubs as charities, but the general practice was to politely dismiss such requests. This was partly because the posture of being superior as whites was the norm among white Americans of this age, and partly because NAWSA believed it had little hope of a national women's suffrage amendment without at least one little support from the southern states who practiced racial segregation .

NAWSA's strategy at the time was to get women to vote in a row in states until there was a critical mass of voters who could push through such an amendment on a national basis. In 1913 the "Southern States Woman Suffrage Committee" was formed to try to steer this process properly. It was run by Kate Gordon, who was the corresponding secretary from 1901 to 1909. Gordon, who was from southern Louisiana, supported women's suffrage but opposed the idea of a national amendment, claiming it would violate state rights. She said this could lead to similar enforcement of African Americans' constitutional right to vote there. A right that must be prevented, and in their opinion rightly so. Their committee was too small to seriously influence the direction of the association, but their public condemnation of the proposed amendment, expressed in a strongly racist form, deepened the wounds within the organization.

Splitting the movement

A serious challenge for the NAWSA leadership group began to develop in 1910 when a young activist named Alice Paul returned to the United States from England, where she had been part of the militant wing of the women's suffrage movement. She was detained there and was force-fed when she started a hunger strike. After joining NAWSA, she became the person who sparked the greatest interest in a national amendment after years of overshadowed state campaigns.

In Shaw's view, the time was ripe for the renewed focus on the amendment. Gordon and Clay, the ongoing opponents of a national amendment in NAWSA, had been outmaneuvered by their opponents and no longer held national offices.

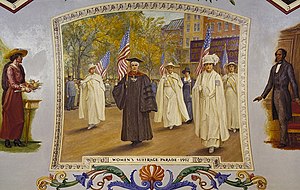

In 1912 Alice Paul was elected chairman of the congressional committee and tasked with reviving the fight for women's suffrage. Together with Burns, Paul organized a “Suffrage Parade” in 1913, called the Woman Suffrage Procession . It took place in the capital, Washington, on the day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration . Male opponents of the march turned the event into almost a disaster with rabble and attacks on women; order could only be restored through the intervention of a cavalry unit. Public outrage over the incident that subsequently cost the police chief his job earned the movement widespread notoriety and gave it a fresh boost.

Paul worried the NAWSA leaders with their arguments. Because the Democrats did not want to introduce women's suffrage, even though they controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress, the women's suffrage movement was supposed to work for the defeat of all Democrats, regardless of the individual candidate's attitudes towards the right to vote. NAWSA's position was the opposite, namely to support any candidate who was in favor of women's suffrage, regardless of party affiliation.

In 1913 Paul and Burns formed the Congressional Union (CU), which was only supposed to campaign for the national amendment, and they sent organizers to states that already had NAWSA sub-associations. The relationship between CU and NAWSA was vague and unclear. Was she a support or an opposition? During Congress in 1913, Paul and her supporters demanded that the organization focus its efforts on a national amendment. Instead, Congress authorized the board to limit the CU's ability to circumvent NAWSA's line. After unsuccessful negotiations to resolve the differences, NAWSA dismissed Paul as chairman of the congressional committees. By February 1914, NAWSA and the CU had effectively split into two independent organizations.

Blatch united her "Women's Political Union" with the CU. That organization instead became the basis for the National Woman's Party (NWP), which Paul created in 1916. Once again there were two competing organizations for women's suffrage, but this time the result was more like a division of labor. NAWSA cultivated its image of respectability and engaged in highly organized lobbying, both at the state and national levels. The smaller MWP was also active as a lobbyist, but became increasingly well known for its drama and confrontational activities, most of which took place in the nation's capital.

Catt's second presidency

Despite the rapid growth in membership of NAWSA, discontent with Shaw grew. Her tendency to overreact to those who disagreed with her had the effect of increasing frictions in the organization. Several members resigned from the board in 1910, and the board experienced a significant change in its composition every year thereafter until 1915.

1914-15

In 1914, Senator John Shafroth tabled an amendment to the United States Constitution that would require state law to allow women to vote in the state if eight percent of voters signed a petition to this effect. NAWSA supported the proposed amendment, while the CU blamed it for abandoning the direction of a national women's suffrage amendment. Membership confusion arose, and the 1914 delegates turned their discontent to Shaw. Shaw had already considered stepping down from the presidency in 1914 but decided to run again. For 1915 she announced that she would not be re-elected.

Catt was the obvious alternative to replacing her, but she was currently running the New York State Woman Suffrage Party, which was in the early stages of a difficult suffrage campaign in that state. The prevailing belief in NAWSA was that success in one of the great Eastern states would tip the scales for the general campaign. New York was the most populous state in the Union, and victory there was a real possibility. Catt agreed to move the work in New York to someone else and to take the presidency of NAWSA in December, on condition that she could assemble her own executive board, which had always been elected at the annual convention. She appointed women as employees who were so independent that they could work full time for the movement.

Strengthened by the increased level of participation and renewed unity in the federal office, Catt sent her staff into the struggle to secure the state of organization and reorganize the campaign for a more centralized and more effective operation. Catt described NASWA as a camel with a hundred humps, each with a blind rider sitting and looking for the way. It created a new form of leadership by directing a stream of messages to the state and local sub-organizations that contained codes of conduct, organizational suggestions, and detailed work plans.

NAWSA had previously devoted much of its efforts to educating the public about women's suffrage, and this had made a significant impact. Women's suffrage had become a major concern of the nation, and NAWSA had become the largest volunteer organization with two million members in the process. Catt built on this basis and converted the association into an organization that was primarily intended to exert political pressure.

1916

At a board meeting in March 1916, Catt described the organization's dilemma as follows:

"The Congressional Union is drawing off from the National Association those women who feel it is possible to work for suffrage by the Federal route only. Certain workers in the south are being antagonized because the National is continuing to work for the Federal Amendment. The combination has produced a great muddle ”.

(German: The 'Congressional Union' withdraws from the 'National Association' those women who feel that it is only possible to work for women's suffrage through the national route. Certain employees in the south have become opponents because the 'National 'continues to work for the State Amendment. That combination has created a lot of confusion. )

Catt believed that NAWSA's cessation of working primarily with state-by-state campaigns had reached its limit. Some states seemed unlikely to ever endorse women's suffrage, in some cases because state laws made constitutional reform extremely difficult, in other cases, particularly in the Deep South, because the opposition was simply too strong. Catt reoriented the organization towards the national women's suffrage amendment, while continuing state campaigns where there was a realistic chance of success.

When the Democratic and Republican parties met for their congresses in June 1916, the suffragists in both put pressure on them. Catt was invited to present her views at the Republican gathering in Chicago. An anti-suffragist spoke after her, and when she told the congregation that the women didn't want to vote, a crowd of suffragists poured into the hall and filled the hallways. They were soaked because they had marched several blocks in the heavy rain on their parade, accompanied by two elephants. When the excited anti-suffragist finished her comments, the suffragists cheered her cause. At the St. Louis Democratic Congress a week later, the suffragists filled the galleries and made their views known during the debate on women's suffrage.

Both parties supported women's suffrage, but only at the state level, which meant that different states could incorporate it in different ways, and in some cases not at all. Expecting more, Catt convened a special congress by moving the date of the 1916 congress from December to September, and began organizing another push for the national amendment. Congress initiated a strategic change by adopting Catt's "Winning Plan". He changed the association's strategy and approved their proposal to make the national amendment a priority for the whole organization and authorized them to form a professional lobby group for the pursuit of the goals in Washington. The board was empowered to develop a plan of work to accomplish this goal in each state, with the option to take the job in any state subsidiary that disagrees. He agreed not to fund federal women's election campaigns unless they met strict requirements. One wanted to avoid efforts that had little chance of success. Catt's plan also contained milestones towards achieving the amendment on women's suffrage around 1922.

President Wilson, whose attitude towards women's suffrage was developing, spoke at the 1916 NAWSA Congress. He had been viewed as an opponent of women's suffrage when he was Governor of New Jersey; but in 1915 he announced that he was traveling from the White House home to his home state to vote in favor of the state's referendum. He spoke positively of women's suffrage at the NAWSA Congress, but then made a U-turn when it came to supporting the amendment. Charles Evans Hughes , his opponent in the presidential election that year, declined to speak at Congress, but went further than Wilson in supporting the amendment.

NAWSA's congressional committee had been in disarray since Alice Paul was removed from it in 1913. Catt reorganized it and made Maud Wood Park chairman in December 1916 . Park and her assistant Helen Hamilton Gardener created what came to be known as the "Front Door Lobby". The behavior was so named by a journalist because it acted openly and avoided the traditional lobbying method of backstairs. A headquarters for this effort was set up in a shabby mansion called "Suffrage House". NAWSA lobbyists stayed here and coordinated their activities at daily conferences in their meeting rooms.

In 1916, NAWSA bought Alice Stone Blackwell 's Woman's Journal . The news paper had been founded in 1870 by Blackwell's mother, Lucy Stone, and had served as the leading voice of the women's movement for most of the time since then. However, it had its typical limitations. It was a small company, with Blackwell doing most of the work himself, with the main reporting focus on the eastern part of the country, at a time when a national paper was needed. After transfer, it was renamed Woman Citizen and merged with The Woman Voter , the New York City Woman Suffrage Party magazine, and National Suffrage News , the former NAWSA journal. The masthead stated that it was the official organ of NAWSA.

1917

In 1917, Catt received a grant of $ 900,000 from Mrs. Frank (Miriam) Leslie for the best use possible in the cause of the women's rights movement. Catt dedicated most of NAWSA's sum, $ 400,000 alone, to the enlargement of the paper, the Woman Citizen .

In January 1917, Alice Paul's NWP began the chain of protesters around the White House, with banners showing demands for women's suffrage. The police gradually arrested 200 demonstrators, many of whom went on hunger strikes in prison. The prison authorities forcibly fed her, causing a public outcry that fueled the social debate about women's suffrage.

When the United States took part in World War I in April 1917, NAWSA actively participated in the war effort. Shaw was appointed chairman of the women's committee for the Council of National Defense, established by the federal government to coordinate war resources and strengthen public morale. Catt and two other NAWSA members served on the executive committee. The NWP, on the other hand, did not participate in the war effort, claiming that NAWSA did so at the expense of electoral work.

In April 1917, Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first woman to sit in Congress after serving personally as a lobbyist and field secretary for NAWSA. Rankin voted against the declaration of war.

In November 1917, the women's suffrage movement achieved a great victory when a referendum on women's suffrage was won by a large majority in New York State, the most populous state in the nation. The powerful political power system of Tammany Hall, which had previously rejected women's suffrage, took a neutral stance on this referendum, in part because the wives of several Tammany Hall leaders had important roles in the suffrage campaign.

1918-1919

The House of Representatives first passed the Suffrage Amendment in January 1918, but the Senate postponed its debate on the matter until September. President Wilson took the unusual step of appearing before the Senate to discuss the matter and request that this amendment be passed as a matter of warfare. The Senate, however, refused to pass it with two missing votes. NAWSA then began a campaign to remove seats from four senators who voted against the amendment by forming a "coalition of opponents" that included unions and prohibitionists. Two of these four senators were voted out of office in the November federal election.

NAWSA held its "Golden Jubilee Congress" in March 1919 at the Statler Hotel in St. Louis, Missouri . President Catt gave the opening speech asking delegates to form a league of women voters. A resolution was passed to establish this league as a separate part of NAWSA, whose membership would come from the states that allowed women to vote. The League was tasked with fully enforcing women's suffrage and influencing legislation that revolved around women in states where they were already allowed to vote. On the last day of Congress, the Missouri Senate passed a bill giving women the right to vote in Missouri presidential elections and a resolution to propose a constitutional amendment to give women full suffrage. In June of the same year the 19th amendment was passed.

Adoption of the 19th Amendment (women's suffrage)

After the election, Wilson convened a special session of Congress that passed the amendment to women's suffrage on June 4, 1919. The battle has now been routed to the state legislature, three-quarters of which were required to ratify the amendment before it could become common law.

Catt and the NAWSA boards of directors had planned their work in support of the ratification process since April 1918, over a year before the amendment was passed by Congress. Ratification committees had already been set up in the capitals of the federal states, each with its own budget and work plan. Immediately after the amendment was passed by Congress, the "Suffrage House" headquarters and the metropolitan lobby organization were closed and resources were diverted to the ratification process. Catt felt a sense of urgency as she expected reform energies to wane after the war that had ended seven months earlier. Many local women's suffrage societies had disbanded in states where women could already vote. This made it harder to organize quick ratification.

At the end of 1919, women could effectively vote in the presidential election in states that held a majority of the electorate . Political leaders, convinced that women's suffrage was inevitable, began pressuring local and national MPs and senators to support it so that their respective parties could take credit for it in future elections. Both Democratic and Republican Congresses voted in favor of the amendment in June 1920.

Former NAWSA members Kate Gordon and Laura Clay organized the opposition to the ratification of the amendment in the southern states. They resigned from NAWSA in the fall of 1918 at the request of the board because they had made public statements against the nationwide amendment. NAWSA concentrated staff and other resources on a Southern campaign in support of ratification. However, they were unable to launch an influential campaign, which fundamentally destroyed hopes that the southern states would support this ratification. Nevertheless, the legislature of the southern state of Tennessee ratified the amendment with a majority on August 18, 1920, thus providing the approval of the last required state.

The 19th Amendment, the Women's Suffrage Amendment to the United States Constitution, became state law on August 26, 1920 when it was certified and signed by the United States Secretary of State .

Conversion into the "League of Women Voters"

NAWSA held its final conference six months before the 19th Amendment was ratified. This meeting on February 14, 1920 established the League of Women Voters as the successor organization of NAWSA with Maud Wood Park , the former chairman of the "Congressional Committee", as president. The League of Women Voters was formed to help women take on a larger share of public duties, having won the right to vote. It was believed that women should exercise their right to vote properly. Before 1973, only women could join the League .

This “League of Women Voters” still exists today as a civil organization.

See also

- History of women's suffrage in the USA

- League of Women Voters article , accessed January 13, 2019.

- feminism

Individual evidence

- ^ National Woman Suffrage Association in US History

- ↑ DuBois 1978

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, Harper (1881-1922), Vol. 2, pp. 171-72

- ↑ Rakow, Kramarae 2001 p. 47

- ↑ Cullen-DuPont 2000 p. 13

- ↑ DuBois 1978 pp. 164-167, 189, 196

- ↑ DuBois 1978 p. 173

- ↑ DuBois 1978 pp. 192, 197

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 p. 17

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 163 163-64

- ^ Solomon, Barbara Miller: In the Company of Educated Women: A History of Women and Higher Education in America , New Haven, Yale University Press 1985. ISBN 0-300-03639-6

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 74-76

- ↑ Dubois 1992 pp. 172-175

- ↑ Ann D Gordon: Woman Suffrage (Not Universal Suffrage) by Federal Amendment . In: Marjorie Spruill Wheeler (Ed.), Votes for Women !: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation , Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press 1995. ISBN 0-87049-836-3

- ↑ Dubois 1992 pp. 172, 183

- ^ Letter from Stanton to Olympia Brown, May 8, 1888.

- ↑ Dubois 1992 p. 183

- ↑ McMillen | 2015 | pp188-190

- ↑ McMillen 2008 pp. 224-225

- ↑ Alice Stone Blackwell: Lucy Stone: Pioneer of Woman's Rights , Boston, Little, Brown, and company 1930. Reprinted by University Press of Virginia in 2001. ISBN 0-8139-1990-8

- ↑ Gordon 2009 pp. 54-55

- ↑ McMillen 2008 pp. 224-225

- ↑ Gordon 2009 pp. 52-53

- ↑ McMillen 2015 pp. 233-234

- ↑ Barry 1988 pp. 283-287

- ↑ Gordon 2009 pp: 54-55

- ↑ Dubois 1992 p. 179

- ↑ Ida Husted Harper The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony , (1898-1908), Vol. 2, p. 632.

- ↑ Barry 1988 pp. 296, 299

- ↑ Katherine Anthony: Susan B. Anthony: Her Personal History and Her Era. New York, Doubleday 1954. p. 391. See also: Harper (1898-1908), Vol. 2, pp. 629-630

- ↑ McMillen 2008 p. 227

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 p. 19

- ↑ Tetrault 2014 p. 137

- ↑ McMillen 2015 p. 23

- ^ Ann D. Gordon: Knowing Susan B. Anthony: The Stories We Tell of a Life . In: Ridarsky, Christine L. and Huth, Mary M., (editors): Susan B. Anthony and the Struggle for Equal Rights . Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press 2012. pp. 202, 204; ISBN 978-1-58046-425-3

- ↑ Lynn Sherr: Failure is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words . New York (Times Books) Random House 1995. p. 310. ISBN 0-8129-2718-4

- ↑ McMillen 2008 p. 228

- ↑ Gordon 2009 p. 246

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1881–1922), Vol. 4, p. 174.

- ↑ Dubois 1992 p. 226

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1881-1922), Vol. 4, pp. 164-165.

- ↑ Dubois 1992 p. 222

- ↑ McMillen 2015 p. 240

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 212-213

- ↑ McMillen 2015 p. 241

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 p. 22

- ↑ Dubois 1992 p. 178

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 pp. 24-25

- ↑ May Wright Sewall (Ed.): The World's Congress of Representative Women . New York: Rand, McNally 1894. p. 48

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 212-213

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 8

- ↑ Dubois 1992 pp. 182, 188-91

- ↑ McMillen 2008 p. 207

- ↑ Wheeler 1993 S. 113-15

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 23

- ^ Wheeler 1993 pp. 115-120

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 7

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 36-37

- ^ Stephen M. Buechler, The Transformation of the Woman Suffrage Movement: The Case of Illinois, 1850-1920 (1986), pp. 154-57

- ↑ Dubois 1992 p. 178

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 43

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 47-48

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 pp. 28-29

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 231-32

- ↑ Franzen 2014 pp. 2, 96, 141, 189. Franzen challenges the traditional view that Shaw was an ineffective leader.

- ↑ Fowler 1986 p. 25

- ↑ Franzen 2014 p. 109

- ↑ Wheeler 1993 S. 120-21

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 39, 82

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 242-46

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 243

- ↑ Maud Wood Park . Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ↑ Jana Nidiffer, "Suffrage, FPS, and History of Higher Education," in Allen, Elizabeth J., et al. (2010), Reconstructing Policy in Higher Education , pp. 45-47 . New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-99776-8

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 55-56

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 51-52

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 241, 251

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 54

- ↑ Marjorie Spruil Wheeler: Introduction: A Short History of the Woman Suffrage Movement in America . In: Marjorie Spruil Wheeler (Ed.): One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement . NewSage Press, Troutdale, Oregon 1995, ISBN 978-0-939165-26-1 , pp. 11, 14.

- ↑ Franzen 2014 pp. 138-39

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 23-24

- ↑ Franzen 2014 p. 8, 81

- ↑ Franzen 2014 p. 189

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 298

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 83, 118

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 255-257

- ↑ Gordon in Wheeler

- ↑ Franzen 2014 pp. 140, 142

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 255-257

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 p. 31

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 257-259

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 257-259

- ↑ Fowler 1986 p. 146

- ^ Mary Walton: A Woman's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot . Palgrave McMillan, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-61175-7 , pp. 133, 158.

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 pp. 32-33

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 241

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 250

- ↑ Franzen 2014 pp. 156–157

- ↑ Franzen 2014 pp. 156, 162

- ↑ Fowler 1986 pp. 28-29

- ↑ Franzen 2014 p. 142

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 265-267

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 265-267

- ↑ Van Voris 1987 p.

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 p. 39

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 83, 118

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 267

- ↑ Fowler 1986 pp. 143-144

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 84-85

- ↑ Van Voris 1987 pp. 131-132

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 87-90

- ↑ Flexner 1959, p. 274

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 271-272

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 187, endnote 25

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 90-93

- ↑ Fowler 1986 pp. 116-117

- ^ "The record of the Leslie woman suffrage commission, inc., 1917-1929", by Rose Young.

- ↑ Fowler 1986 pp. 116-117

- ↑ Fowler 1986 pp. 118-119

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 275-279

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 103

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 276, 377, endnote 16

- ↑ Van Voris 1987 p. 139

- ↑ Scott, Scott 1982 p. 41

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 282

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp: 283, 300-304

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 119-122

- ↑ Katharine T. Corbett: In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women's History . St. Louis, MO, Missouri History Museum 1999

- ↑ Flexner 1959 pp. 307-308

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 129-130

- ^ Graham 1996 pp. 127, 131

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 141, 146

- ↑ Graham 1996 pp. 118, 136, 142

- ↑ Graham 1996 p. 130

- ↑ Flexner 1959 p. 316

- ↑ Kay J. Maxwell: The League of Women Voters Through the Decades! - Founding and Early History . April 2007, Ed .: League of Women Voters.

literature

- Adams, Katherine H. and Keene, Michael L. Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign . Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07471-4

- Kathleen Barry: Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist . Ballantine Books, New York 1988, ISBN 0-345-36549-6 .

- Anne Boylan: Women's Rights in the United States: A History in Documents . Oxford University Press, New York 2016, ISBN 0-19-533829-4 .

- Kathryn Cullen-DuPont: The Encyclopedia of Women's History in America , second. Edition, Facts on File, New York 2000, ISBN 0-8160-4100-8 .

- Ellen Carol DuBois: Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869 . Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY 1978, ISBN 0-8014-8641-6 .

- Ellen Carol DuBois (Ed.): The Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Susan B. Anthony Reader . Northwestern University Press, Boston 1992, ISBN 1-55553-143-1 .

- Eleanor Flexner: Century of Struggle . Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1959, ISBN 978-0-674-10653-6 .

- Robert Booth Fowler: Carrie Catt: Feminist Politician . Northeastern University Press, Boston 1986, ISBN 0-930350-86-3 .

- Trisha Franzen: Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage . University of Illinois Press, Urbana 2014, ISBN 978-0-252-07962-7 .

- Jo Freeman: We Will Be Heard: Women's Struggles for Political Power in the United States . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., New York 2008, ISBN 0-7425-5608-5 .

- Elizabeth Frost-Knappman, Kathryn Cullen-DuPont: Women's Suffrage in America . Facts on File, New York 2009, ISBN 0-8160-5693-5 .

- Ann D. Gordon (Eds.): The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: Their Place Inside the Body-Politic, 1887 to 1895 , Volume 5 of 6. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ 2009, ISBN 978-0-8135-2321-7 .

- Sara Hunter Graham: Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy . Yale University Press, New Haven 1996, ISBN 0-300-06346-6 .

- Elisabeth Griffith: In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton . Oxford University Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0-19-503440-0 .

- Sally Gregory McMillen: Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women's Rights Movement . Oxford University Press, New York 2008, ISBN 0-19-518265-0 .

- Sally Gregory McMillen: Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life . Oxford University Press, New York 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-977839-3 .

- Lana F. Rakow, Cheris Kramarae (Eds.): The Revolution in Words: Righting Women 1868–1871 , Volume 4 of Women's Source Library . Routledge, New York 2001, ISBN 978-0-415-25689-6 .

- Anne Firor Scott, Andrew MacKay Scott: One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage . University of Illinois Press, Chicago 1982, ISBN 0-252-01005-1 .

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B .; Gage, Matilda Joslyn; Harper, Ida (1881-1922). History of Woman Suffrage in six volumes. Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony (Charles Mann Press).

- Lisa Tetrault: The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 . University of North Carolina Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1-4696-1427-4 .

- Jacqueline Van Voris: Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life . The Feminists Press at the City University of New York, 1987, ISBN 978-1-55861-139-9 .

- Walton, Mary. A Woman's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 978-0-230-61175-7

- Marjorie Spruill Wheeler: New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States . Oxford University Press, New York 1993, ISBN 0-19-507583-8 .

Web links

- The National American Woman Suffrage Association

- National Woman Suffrage Association

- Timeline: "One Hundred Years toward Suffrage: An Overview" (engl.)

- The "League of Women Voters" in the English Wikipedia

- Women's suffrage. From the Library of Congress

- National American Woman Suffrage Association: A Register of Its Records in the Library of Congress . Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. 1974. Archived from the original on December 8, 2009. Retrieved on August 3, 2010.

- Votes for Women, Selections from the National American Woman Suffrage Association 1848-1921

- Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller's NAWSA Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897-1911

- Webcast-Catch the Suffragist's Spirit; The Miller Scrapbooks From the Library of Congress