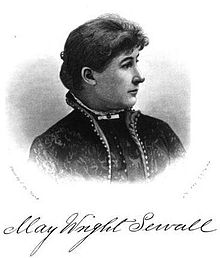

May Wright Sewall

May Wright Sewall , née Mary Eliza Wright (born May 27, 1844 in Greenfield , Milwaukee County ; died July 22, 1920 in Indianapolis ) was an American suffragette and peace and social activist.

Personal life and career

Mary Eliza Wright was the fourth child and second daughter of the teacher and farmer Philander Wright and his wife Mary, nee Brackett. They were from New England , married in Ohio, and then moved to Wisconsin . Already in childhood she heard the name May. She was brought up by her father in home schooling, but also attended local schools and eventually became a teacher. She taught in Waukesha County from 1863 to 1865 , then pursued higher education and attended the women's school in Evanston, what would become Northwestern University . She completed two degrees there in 1866 and 1871; in the meantime she taught again and was also the primary school principal. Her subjects included English, German and later literature courses.

From 1872 to 1875 May Wright was first married to math and economics teacher Edwin W. Thompson and moved with him to Indiana, but he died on August 19, 1875 of tuberculosis . In her second marriage from 1880 to 1895 she married the teacher and school founder Theodore Lovett Sewall, with whom she lived in Indianapolis as an equal partner. The couple moved in the upper classes of society and regularly received politicians, artists and socially engaged citizens and activists. She never had children in any marriage; her second husband also died of tuberculosis.

Until 1907 Wright-Sewall taught in the high school that her second husband had founded with her as principal, although the school building changed a few times. In contrast to traditional girls' education institutions, the focus of the lessons was not on arts subjects, but on academic education and languages. Sewall reformed the dress code at her school by making clothing and footwear that are simpler and more comfortable than the fashion of the time. The school also offered exercise classes for girls and was one of the first in the United States to offer classes in science and home studies. The courses at Sewalls School thus prepared the way to study.

It was not until 1900 that there was competition with the public high schools that were being established ; in addition, Sewall was controversial because of its educational reform zeal. She teamed up with Stanford graduate Anna F. Weaver in 1905, who took over the school from her in 1907 but had to close in 1910. Sewall herself moved in 1907 to Eliot in York County and from there to Cambridge near Boston, where she continued her work for the women's rights movement.

Honorary positions and activities

May Wright Sewall was known in Indianapolis for her diverse cultural and voluntary commitment, which, according to her critics, was even very dominant. In addition to a contemporary club , which the couple held in the manner of a salon, she also founded the city's women's club, in which the wife of Governor Thomas A. Hendricks was the first president and which is still active today in society and in mutual self-help. The Indianapolis Museum of Art later emerged from the art exhibition founded by Sewall . The associated art institute named her after her friend, founder John Herron. Today it is part of Indiana University as the "Herron School of Art and Design" . She also founded the “Indianapolis Propylaeum” as an artistic and cultural meeting place.

Sewall had been active as a suffragette since 1878 and was a very active advocate of the right to vote for women between 1880 and 1883, which was finally decided by the state parliament, but not accepted by the Indiana Senate. Sewall then turned to the national level to achieve this goal. Already a member since 1878, she was chairman of the executive committee of the National Woman Suffrage Association from 1882 to 1890 , which was also merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association at her instigation . For a long time, Sewall endorsed the idea of women's councils to organize women and unite them into a social force. After Sewall had convinced the prominent women leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony of the concept, the women founded the National Council of Women of the United States in 1888 as the national umbrella organization of the women's movement and the International Council of Women as the international mouthpiece. The development of this organization was initially sluggish despite participants from several countries (including Clara Barton , Frances Willard , Antoinette Brown Blackwell , Julia Ward Howe , Lucy Stone ) and only picked up speed around the turn of the century. In the 1890s Sewall was therefore also active in Europe in order to win supporters. From 1897 to 1899 Sewall was president of the national, then from 1899 to 1904 president of the international umbrella organization ICW. There she was also involved as an engine for the peace movement.

She was the first vice-president of the General Federation of Women's Clubs , founded in 1890 , but was disappointed in her expectations of being able to lead these clubs into the councils. At the World's Congress of Representative Women , which took place in 1893 on the occasion of the World's Fair in Chicago , Sewall was a central organizational figure and was denigrated by Bertha Palmer as a radical feminist. US President McKinley sent her to the Paris World's Fair in 1900 as the representative of US women .

In 1904, Sewall became chair of the Standing Women's Committee for Peace and prepared a peace conference that took place during the 1915 World Exposition in San Francisco . In the same year she joined Henry Ford's private peace mission to Europe, the Peace Ship , which returned unsuccessfully to the USA in the spring of 1917. Soon afterwards, Sewall withdrew from the public for an unusually long time.

It was only shortly before her death in 1920 that she announced in a book that had been in preparation since 1916 that by 1897 she was no longer a strict Unitarian , but actively practiced spiritualism . This had been largely unknown before.

Works

- The Higher Education of Women (1915)

- The Woman Suffrage Movement in Indiana (1915)

- Women, World War and Permanent Peace (1915)

- Neither Dead Nor Sleeping (1920)

Honors

- The Sewall Memorial Torches lantern pillars at the Indianapolis Museum of Art have been a reminder of her life's work since 1923 .

- The May Wright Sewall Leadership Award has been honoring women who do volunteer work in Indianapolis since 2005.

literature

- Ray E. Boomhower: Fighting for Equality: A Life of May Wright Sewall . Indianapolis 2007, Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87195-253-0 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sewall, May Wright |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wright, Mary Eliza |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American suffragette and peace and social activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 27, 1844 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Greenfield , Milwaukee County |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 22, 1920 |

| Place of death | Indianapolis , Indiana |