Necromenia

In biology, necromenia is the interrelation between organisms of different species, in which one partner benefits from the death of the other without causing or accelerating it itself. In contrast to parasitism , the host organism is not damaged during its lifetime.

Forms of necromenia

Some necromancerous animal species, like some parasites, can develop permanent stages that serve to colonize other organisms. In this resting phase, your metabolism is reduced to a minimum. Only when the colonized animal has ended its life cycle or dies due to adverse external circumstances does the permanent stage develop into a complete organism again, which feeds on the microorganisms and other destructive elements on the decaying animal.

In other cases, necromenia is derived from the phoresia , in which smaller living beings use larger, often airworthy animals as a means of transport. They become widespread through this behavior and, as commensals, use the same food sources as their larger carriers. Some of these phoretically living animals, however, no longer leave the carrier organism until after its death. Only then do they develop further with the help of the new energy sources on the decomposing organism.

Examples

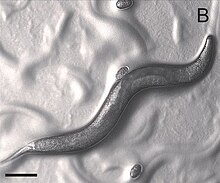

Well-known examples are roundworms that are associated with various types of beetles or millipedes and other ground-dwelling organisms. After the animals die, they feed on the bacteria , fungi and other roundworm species on the dead organisms. Among the nematodes, the genera Pristionchus and Rhabditis , which show necromenic behavior, have been well studied.

The mite species Histiostoma polypori and Histiostoma maritimum from the Histiostomatidae family use insects for phoresis, but unlike many related mite species, they only develop on the carcasses of their transporters.

Necromenia is more widespread than was originally thought when you consider that the bacteria that nourish the roundworms remain largely undigested. They also use the worm's digestive tract for onward transport and in the event of its death it also serves as a food source for these saprobionts .

Developmental significance

In the development history of an individual living being, necromenia is not necessarily mandatory for the completion of its life cycle up to sexual maturity. The roundworm Caenorhabditis vulgaris can colonize both the sea lice of the genus Armadillidium and the glossy snails of the genus Oxychilus with permanent stages, but in the laboratory it can complete its life cycle without a host organism if it has the appropriate bacterial lawns as a source of food. Necromenia is therefore optional for this species, but in addition to spreading through phoresia, it has the advantage of a protected environment with a rich food supply after the host animal's death.

Some scientists see the necromenia of nematodes as a precursor to parasitism. Many types of roundworms live parasitically and feed at the host's expense while the host is still alive. These infectious forms use the same mechanisms as their necromancerous relatives. Very similar genes and signaling pathways in their cells are responsible for this as in the species that do not damage their carriers.

Research history

George Poinar reported in 1986 in the first description of the nematode Rhabditis myriophila by the strange behavior of the worm, which in a juvenile stage through the mouth into the digestive tract of Doppelfüßers Oxidus gracilis entered, but where he did no harm, but remained in a steady state. Poinar observed that Rhabditis myriophila could only develop to sexual maturity as soon as its host organism had passed into the stage of decomposition. In 1989, Walter Sudhaus from the Free University of Berlin, together with Franz Schulte, published the first description of a nematode that showed the same behavior. The term "necromenie" (English: necromeny ) was coined for this. It is derived from the ancient Greek words νεκρός ( nekrós ) , corpse 'and μένειν ( meneín ) , waiting' and means "waiting for the carcass ". The newly discovered roundworm species was therefore called Rhabditis necromena .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Catarina Pietschmann: And the round worm has teeth. MaxPlanckResearch - The Knowledge Magazine of the Max Planck Society, 1, pp. 51–57, 2014, p. 57 ( PDF , German)

- ^ A b Walter Sudhaus & Franz Schulte: Rhabditis (Rhabditis) necromena sp. n. (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) from south Australian diplopoda with notes on its siblings R. myriophila Poinar, 1986 and R. caulleryi Maupas, 1919. Nematologica 35, 1, pp. 15-24, Brill Online Books and Journals, Leiden 1989 doi : 10.1163 / 002825989X00025

- ↑ Karin Kiontke & Walter Sudhaus: Ecology of Caenorhabditis species. Worm Book, The Online Review of C. elegans Biology, January 9, 2006 doi : 10.1895 / wormbook.1.37.1 Online

- ↑ F. Schulte: Necromenie - 'controlled' parasitism between rhabditis species and soil animals ?. Negotiations of the German Zoological Society, 82, p. 248, 1989

- ↑ Stefan Wirth: Phylogeny, Biology and character transformations of the Histiostomatidae (Acari, Astigmata). Dissertation at the Free University of Berlin, Department of Biology, Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2004 ( PDF, English )

- ↑ Robbie Rae, Metta Riebesell, Iris Dinkelacker, Qiong Wang, Matthias Herrmann, Andreas M. Weller, Christoph Dieterich, Ralf J. Sommer: Isolation of naturally associated bacteria of necromenic Pristionchus nematodes and fitness consequences. Journal of Experimental Biology, 211, pp. 1927-1936, 2008 doi : 10.1242 / jeb.014944

- ↑ Scott E. Baird, David HA Fitch, Scott W. Emmons: Caenorhabditis vulgaris sp.n. (Nematoda: Rhabditidae): A necromenic associate of pill bugs and snails. Nematologica, 40, 1-4, pp. 1-11, 1994

- ^ Walter Sudhaus: Evolution of insect parasitism in rhabditid and diplogastrid nematodes. In: SE Makarov & RN Dimitrijevic (eds.): Advances in arachnology and developmental biology. Monographs, 12, pp. 143-161, Vienna-Belgrade-Sofia 2008 PDF

- ↑ George O. Poinar Jr .: Rhabditis myriophila sp. n. (Rhabditidae: Rhabditida), Associated with the Millipede, Oxidis gracilis (Polydesmida: Diplopoda). Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington, 53, 2, pp. 232-236, 1986 PDF

literature

- Walter Sudhaus & Friedrich Schulte: Rhabditis (Rhabditis) necromena sp. n. (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) from south Australian diplopoda with notes on its siblings R. myriophila Poinar, 1986 and R. caulleryi Maupas, 1919. Nematologica 35, 1, pp. 15-24, Brill Online Books and Journals, Leiden 1989 doi : 10.1163 / 002825989X00025

- Walter Sudhaus: Redescription of Rhabditis (Oscheius) tipulae (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) Associated with Leatherjackets, Larvae of Tipula paludosa (Diptera: Tipulidae) . Nematologica, 39, 1, pp. 234-239, Brill Online Books and Journals, Leiden 1993 doi : 10.1163 / 187529293X00187