Cohort study

| Hierarchy of study types |

|---|

|

randomized controlled study |

A cohort study is an observational study design of epidemiology with the aim of uncovering a connection between one or more exposures and the occurrence of a disease. A group of exposed and a group of non-exposed people are observed over a certain period of time with regard to the occurrence or mortality of certain diseases. It is a special form of panel investigation in which all persons belong to a sample of the same cohort. A cohort is a group of people in whose résumés a specific biographical event occurred at approximately the same point in time. Depending on the defining characteristic, a distinction is made between birth cohorts, school enrollment cohorts, divorce cohorts and many others.

To establish a connection, the number of new cases ( incidence ) in exposed and non-exposed persons is measured and compared at the end of the investigation . If there is a positive connection between an exposure and a disease, the proportion of sick people in the group of exposed persons is higher than that of the non-exposed study group. Exposure can therefore be a possible risk factor. In order to ultimately make statements about the strength of the association, the two incidence rates are compared and the relative risk is calculated.

Germany's largest cohort study is the National Cohort , which started in October 2014 and is planned for a period of 20 to 30 years .

Application of cohort studies

Cohort studies are often used to investigate developmental and generational sociological issues. A characteristic cohort study is, for example, the "British National Child Development Study" (NCDS) by Ferri and Sherpherd from 1992, which shows the development of 11,400 children born in Great Britain from March 3 to 9 in terms of education, attitudes, income and health examined over a period of 34 years with five survey times.

The following hypothetical cohort study examined the effect of cigarette smoking (exposure) on the incidence of coronary artery disease in order to illustrate the approach of the study design. The participants in the study groups showed no heart disease beforehand. At the second time of the investigation, questions were asked about the occurrence of coronary heart diseases and the results were sorted into the four-field table.

| Nicotine consumption | Coronary artery disease occurs | Coronary artery disease does not occur | total | Incidence per 1000 per year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking cigarettes (exposed) | 84 | 2916 | 3000 | 28.0 |

| No Smoking Cigarettes (Unexposed) | 87 | 4913 | 5000 | 17.4 |

With the help of the relative risk, indications of the strength of a possible connection can be found. This is calculated as the quotient of the two rates: (28.0 / 1000): (17.4 / 1000) = 1.6 According to this, cigarette smokers have a 1.6 times higher risk of developing coronary artery disease.

Forms of cohort studies

A distinction is made between two types of cohort studies: intra- and inter-cohort comparisons. The intra- cohort comparison examines the development of certain characteristics of a cohort over time. In contrast, inter- cohort comparisons compare members of different cohorts with one another. The prerequisite, however, is that the people have the same time interval between the respective defining characteristic at the time of the examination.

Prospective and retrospective cohort studies

The cohort design can be done in two different ways. On the one hand, the cohort can be compiled in the present and monitored into the future (prospective cohort study). On the other hand, with a retrospective or historical study arrangement, data from the past is used in order to evaluate it in the present. The prospective study arrangement can in part be based on a long observation period. Because first the cohort is determined without knowing whether and when a disease will occur at all. A well-known example of this approach is the Framingham Heart Study , which began in 1948. The timing of data collection is the only difference between the two types. If a risk factor is recorded in the past (retrospectively) but the cohort is observed over years (prospectively), this type of cohort study cannot be clearly classified as retrospective or prospective. Prospective cohort studies are added to the longitudinal studies, whereby longitudinal studies can in principle also be retrospective.

Recruitment of the study population

The study population can also be recruited in two ways. The study group can be based on exposure and non-exposure, for example smokers and non-smokers. Another possibility is to select a population, for example a city, before these have been characterized in terms of different characteristics. It is possible to examine the study population with regard to several characteristics, as is also the case with the Framingham Heart Study.

Observation over time - follow-up

The observation period depends on the outcome, i.e. the disease. While studies on exposure during pregnancy and malformations in children can be used to make statements after nine months, chronic diseases appear much later. Thus the investigation period also differs. In a cohort study, it must also be ensured that the study population can be examined or questioned at at least two points in time. This is the only way to make statements about a possible connection.

Possible bias in cohort studies

There are various distortions (English bias ) that may arise in this study design. For example, there can be a distortion due to the different quality of the information in exposed and non-exposed subjects. There can also be a further bias due to a lack of participation or early withdrawal from the follow-up observation. This makes the interpretation of the study results much more difficult. The distortions must either be avoided or accepted.

Interpretation and problems

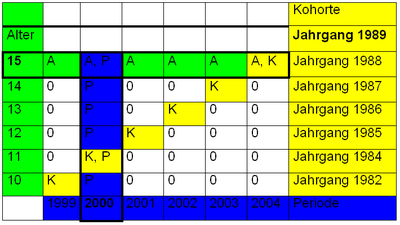

The changes observed in cohort studies are due to three factors:

- Age effect or life cycle effect : (e.g. increasing fear; many people sign a building society loan agreement at the age of 18, risk of divorce in the third year of marriage)

- Cohort effect or age group effect : (e.g. setting of 68 ; born in 1989 (ten years old in 1999), above average number of cinema tickets for the film "1989")

- Period effect or annual effect : (e.g. hamster purchases before disasters; in 2004, an above-average number of people bought a 2005 calendar)

The term "aging effects" describes the effects of aging. Period effects are assumed if the changes correlate with the calendar time. Cohort effects describe the influences of the cohort membership. One problem with the interpretation of cohort studies is that the three mentioned effects can only be separated in individual studies if additional assumptions are made. This is known as the identification problem.

Advantages and disadvantages of cohort studies

A cohort study enables a direct determination of the new disease rate ( incidence ) and thus represents an opportunity to determine indications of the possible risk of exposure to diseases. However, many study participants are often necessary to obtain these results, which makes the study design expensive and time-consuming. Another disadvantage is that the results are only available after a long time and are not suitable for rare outcomes.

See also

- Long-term study

- Long-term archiving

- PAQUID cohort study to identify the causes of dementia and Alzheimer's disease

literature

- David A. Grimes, Kenneth F. Schulz: Cohort studies: marching towards outcomes. In: Lancet . 359, 2002, pp. 341–345, online (PDF; 203 kB) ( Memento from February 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- Rüdiger Jacob, Willy H. Eirmbter: General population surveys . Introduction to the methods of survey research with help for creating questionnaires. Oldenbourg, Munich et al. 2000, ISBN 3-486-24157-5 , p. 347.

- Rainer Schnell , Paul B. Hill, Elke Esser: Methods of empirical social research. 7th completely revised and expanded edition. Oldenbourg, Munich et al. 2005, ISBN 3-486-57684-4 , pp. 244-245.

- Christel Weiß: Basic knowledge of medical statistics. 5th edition. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-642-11336-9 , section 13.4.

- Robert H. Fletscher, Suzanne W. Fletscher: Clinical epidemiology. Basics and application. 2nd Edition. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2007, ISBN 978-3-456-84374-2 .

- Leon Gordis: Epidemiology. 4th edition. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2009, ISBN 978-1-4160-4002-6 .

- Oliver Razum, Jürgen Breckenkamp, Patrick Brzoska: Epidemiology for Dummies. 2nd Edition. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-527-70725-6 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann Faller, Hermann Lang: Medical Psychology and Sociology . Springer-Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-12584-3 , p. 69 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Leon Gordis: Epidemiology. 4th edition. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2009, pp. 167-170.

- ↑ Oliver Razum, Jürgen Breckenkamp, Patrick Brzoska: Epidemiology for Dummies. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Munich 2009, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ E. Ferri, P. Sherperd: National Child Development Study: Prospectus for Analysis. In: ESRC data archive bulletin. ISSN 0307-1391 , 50, 1992, pp. 6-11.

- ↑ Leon Gordis: Epidemiology. 4th edition. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2009, pp. 167-170.

- ↑ Robert H. Fletscher, Suzanne W. Fletscher: Clinical epidemiology. Basics and application. 2nd Edition. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2007, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Marcus Müllner: Successful scientific work in the clinic: Evidence Based Medicine . Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-7091-3755-0 , pp. 77 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hermann Faller, Hermann Lang: Medical Psychology and Sociology . Springer-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-662-46615-5 , pp. 73 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Simone Rothgangel, Julia Schüler: Short textbook medical psychology and sociology . Georg Thieme Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-136422-7 , p. 160 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Leon Gordis: Epidemiology. 4th edition. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2009, pp. 170-172.

- ↑ Oliver Razum, Jürgen Breckenkamp, Patrick Brzoska: Epidemiology for Dummies. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Munich 2009, pp. 165-168.

- ↑ Leon Gordis: Epidemiology. 4th edition. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp. 174-175.

- ^ Norval D. Glenn: Distinguishing Age, Period, and Cohort Effects. In: Jeylan T. Mortimer, Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.): Handbook of the life course. Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers, New York NY et al. 2003, ISBN 0-306-47498-0 , pp. 465-476.

- ↑ Robert H. Fletscher, Suzanne W. Fletscher: Clinical epidemiology. Basics and application. 2nd Edition. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2007, p. 120.

- ↑ Oliver Razum, Jürgen Breckenkamp, Patrick Brzoska: Epidemiology for Dummies. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Munich 2009, p. 168.