Freedom of the press in Turkey

The press and freedom of expression in Turkey is by Article 26 of the Turkish Constitution guarantees in 1982, but suspended de facto ongoing interventions.

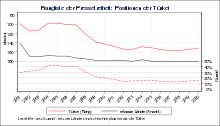

Turkey is one of the countries with the highest number of journalists in prison in the world, ranking 157th out of 180 on the freedom of the press in 2019 .

Legal situation

Legal situation

The Turkish constitution guarantees freedom of the press and freedom of expression. Turkey signed the UN Convention on Human Rights , which, in Article 19, guarantees the right of every person to freedom of expression, including the right to express his or her opinion and to hear the opinions of others. Article 19 prohibits state censorship.

Legal restrictions

In 2014 the Turkish parliament passed a new internet law. The Internet law stipulates that in the event of a violation of their personal rights or their privacy, those affected can turn to the telecommunications authority (Turkish Telekomünikasyon İletişim Başkanlığı ), who then have the right to have the URL blocked by the provider. The applicant must then bring about a decision at the magistrate's court within 24 hours. The court also has the right to block the entire website. If there is no decision from the court within 48 hours, the blocking of the URL is automatically unblocked. Some provisions of the Internet Act were repealed by the Constitutional Court in December 2015. This involved questions of the procedure when the relevant legal violations are published on other websites, or the provision and forwarding of user data to the authorities.

Affected journalists, civil rights activists, politicians from the opposition parties and a number of international organizations see the law as a restriction on freedom of the press and freedom of expression. Reporters Without Borders and the Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ) as well as the EU and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) criticized the Internet law.

The legal practice, which can lead to interference with the freedom of the press, was criticized by the Foreign Office: "The criminal offense of" supporting terrorism "is deliberately stretched in many cases in order to initiate investigations against journalists."

The journalist Fatih Cicek wrote in May 2013: “The very abstract and broadly worded paragraphs of the Criminal Code make it easier for journalists to associate professional activities with illegal political movements or coup plans. Some of the most frequently used paragraphs of the Criminal Code overlap with principled research methods. This includes speaking to security officers and receiving documents. These include Section 285 (violating the confidentiality of an investigation) and Section 288 (attempting to influence a process). "

Arrangements

After several attacks in Turkey, courts imposed a news blackout on all media. For example, after the attack in Reyhanli in 2013, a court in nearby Antakya imposed a four-day blackout.

The short message service Twitter was also blocked several times for Turkish users on court orders.

Between April 29, 2017 and January 15, 2020, all of Wikipedia was blocked in Turkey .

chronology

The work situation for foreign journalists in Turkey has deteriorated since 2014. In addition to a residence permit, journalists need an accreditation from the Turkish state; this is issued for a limited period by the Turkish press office in Ankara. In 2016, the press office refused Hasnain Kazim , who had been Spiegel Online's correspondent in Turkey until then, to extend his accreditation. Kazim finally left Turkey in March 2016.

Apparently, the Turkish authorities keep lists of undesirable media representatives (“ black lists ”).

The German Foreign Office wrote in an assessment that in Turkey there are “in practice [...] time and again serious problems for reporters. The freedom of the press is being massively attacked by politicians again and again. Journalists are often faced with legal proceedings, both in the area of criminal and civil law. Journalists are repeatedly arrested, although the figures are viewed very differently here. ”In particular, in the action taken by state agencies under the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan against the Gülen movement , freedom of the press was“ massively attacked ”.

In April 2016, Turkey repeatedly refused entry to reporters and journalists. Three cases should be mentioned: The US journalist David Lepeska (he works for The Guardian , Al Jazeera and Foreign Affairs ) was denied entry to Turkey. The ARD television journalist Volker Schwenck entry to Turkey was denied, even though he was only in transit to Syria, the image photojournalist Giorgos Moutafis was denied entry, even though he made only a one-day stopover on the trip to Libya. The Dutch reporter Ebru Umar was temporarily arrested in April 2016 after criticizing President Erdoğan.

After the failed coup attempt in Turkey on July 15 and 16, 2016, the government took massive action against journalists, newspapers (editorial offices and publishers), radio and television stations. In the week after the attempted coup, the RTÜK authority , which is responsible for private broadcasters, withdrew their broadcasting licenses from a total of 24 radio and television stations. Connections to the Gülen movement, which the Turkish government blames for the coup attempt, were found on the broadcasters. Thousands of judges, prosecutors, police officers and other civil servants were detained or released; a state of emergency has been declared; the rule of law is apparently no longer in force.

The German Association of Journalists (DJV) called on Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier to work with Turkish authorities. On April 27, 2016 there was a current hour in the Bundestag on freedom of the press and freedom of expression in Turkey.

Numerous international organizations protested against the actions of the Turkish government after the coup attempt, including the Committee to Protect Journalists , the Special Representative of the UN Human Rights Council and the OSCE . They appealed to the Turkish government to stop the disproportionate actions against unpopular journalists and media.

In May 2017 , the head of the satirical magazine Nokta was sentenced to twenty-two and a half years in prison for a cartoon critical of Erdoğan .

Freedom of the press in the context of the EU membership negotiations

An important criterion in the process of possible EU membership for the EU is freedom of expression and freedom of the press in Turkey.

Aryeh Neier wrote in February 2013: “Although the Turkish government is to blame for the steep fall in press freedom, the policies of the European Community and the United States also contributed. The EU said human rights were a determining factor in whether Turkey would be accepted as a member. Nonetheless, Europe seemed to be turning its back on the country during a period of rapid progress on this issue. This undermined those who campaigned for human rights reforms in Turkey. Their claims that improvements would lead to progress in the accession negotiations were proven false and officials lost an important incentive. "

See also

- Human rights in Turkey # Freedom of expression

- History of Turkey , section on rapprochement with the EU in the 21st century

- List of journalists detained in Turkey

- Special cases:

literature

- Turkey: media order on the way to Europe? Documentation of the scientific conference Deutsche Welle Mediendialog April 2011 (Edition International Media Studies)

Footnotes

- ↑ a b Federal Foreign Office: Country Information Turkey. Retrieved April 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Reporters Without Borders : [1] loaded on August 9, 2019.

- ↑ n-tv news television: press ranking criticizes Turkey and Poland: Germany falls behind in terms of freedom of the press. In: n-tv.de. Retrieved April 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Freedom of Expression ›Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In: www.menschenrechtserklaerung.de. Retrieved April 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Anayasa Mahkemesi'nin İnternet Yasası kararı ne anlama geliyor? Hürriyet from December 9, 2015 (Turkish)

- ^ Spiegel Online, Hamburg Germany: Turkey: How Erdogan gags the press. In: Spiegel Online . Retrieved April 21, 2016 .

- ^ Cultural and educational policy, media. In: Foreign Office. Retrieved April 26, 2016 .

- ↑ www.fatihcicek.eu/

- ↑ Fatih Cicek: press freedom in Turkey. In: TheEuropean. May 3, 2013, accessed April 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Wikipedia blocked in Turkey. Retrieved April 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Wikipedia is accessible again. January 16, 2020, accessed January 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Turkey: "Black lists" for journalists cause outrage. In: WEB.DE News. Retrieved April 26, 2016 .

- ^ Cultural and educational policy, media. In: Foreign Office. Retrieved April 26, 2016 .

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ spiegel.de

- ↑ Turkey: 24 radio and TV stations are no longer allowed to broadcast. Retrieved July 19, 2016 .

- ↑ bundestag.de

- ↑ Press freedom groups condemn Turkish media crackdown. In: Guardian . Retrieved July 29, 2016 .

- ↑ More than 22 years imprisonment for the boss of a Turkish satirical magazine , Salzburger Nachrichten, May 23, 2017

- ↑ www.opensocietyfoundations.org

- ^ Aryeh Neier: The steep fall in Turkish freedom of the press . In: Welt Online . February 18, 2013 ( welt.de [accessed April 26, 2016]).