Ladle

A ladle sieve , also called a ladle form, is a tool used in the traditional production of hand- scooped paper, hand-made paper or using the pouring method, a manual method for paper production originally from China , in which the paper fibers are poured into a sieve floating on a pond (today only used in Nepal , Bhutan and Northern Thailand).

history

The first Chinese ladle sieves were made of horsehair , silk and bamboo , and fresh plant stems made of reeds or other grasses. They were braided together to make a flexible mat. The first sieves did not have a removable frame, later the hand-scooping form of the Chinese consisted of a frame in which a fine bamboo mesh connected with silk threads or animal hair was loosely attached and on which a lid was placed when scooping so that no substance could run off from the side . Later the Arabs used bronze wire for this . In East Asian papermaking, the manufacturers use screens that are covered with cloth, some of them still today. The textile screens are particularly suitable for the potting procedure in which the pulp is not drawn from the water, but is poured into the sieve. Then the rigid Schöpfsieb of metal wire was introduced in Europe, and later the grating were copper , brass , galvanized steel, aluminum and stainless steel wire or fibers produced.

technical structure

It is a rectangular wooden frame, the bottom of which forms a fine grid with its own wooden frame. The ladle screen consists of two parts, the screen frame mold (sieve) and the mold frame cover (frame) . There are two western types: the ribbed ( Vergé ) and the woven ( Velin ) form. The ribbed shape is similar to the Japanese Sugeta , except that the ladle is firmly attached to the shape and consists of thin wires. The grid leaves an individual pattern of so-called rip and warp lines in the paper . The wooden frame ( lid ) can be removed to place the fresh sheet on a felt. The size of the paper sheet is determined by the size of the screen. The lattice threads parallel to the long edge are tight and are the ribs. The webs run at right angles to the ribs at a distance of a few centimeters from one another. To create a watermark , an additional and raised contour made of wire is applied to a metal ladle. At this point, the paper will be thinner and therefore more translucent than the larger part of the sheet.

The scooping frame is made of a particularly water-resistant and therefore hardly deforming wood. It was often hung on a wooden seesaw that was mounted overhead and resilient to make it easier for the papermakers to do the physically difficult scooping work. With it, sheets were usually produced up to a format of 42 × 33 cm and in smaller numbers also with larger dimensions.

Handling of the ladle sieve

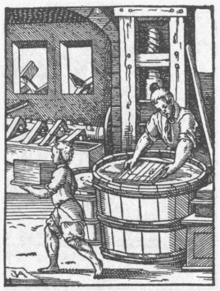

The slurry made of rag or cellulose is scooped out of the vat with the ladle sieve, the excess water drips through the sieve and the solid fibrous matter remains on the sieve. The scoop has to shake the frame skillfully in order to achieve the highest possible consolidation of the fibers among each other. A second papermaker (the gautscher) falls (gautscht) the screen with the fresh paper onto a felt and leaves it for a moment. In the meantime the papermaker takes a second sieve and inserts it into the frame for scooping again. A little later the felt has sucked some water out of the paper pulp and this causes the pulp to solidify under the sieve. The second man removes the first sieve and places another felt on the sheet that has just been deposited, whereupon the next sheet can be drained. A total of 181 sheets between 182 felts are attached to the vat using the traditional method. The process also includes a couch press , in which the pile of felt and paper was pressed to dry the paper. A third papermaker took the still damp sheets of paper from the felt pile and hung them up.

Web links

- http://wp.radiertechniken.de/werkzeuge/papier/

- FILM: die papiermacher - papermaking according to old craft tradition .

Individual evidence

- ^ Josep Asunción: The Complete Book of Papermaking. Lark Books, 2003, ISBN 1-57990-456-4 , p. 63.