Disc meniscus

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| M23.1 | Disc meniscus (congenital) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

A disc meniscus ( Latin meniscus disciformis ) is an anatomical variant of the menisci of the knee joint . The disc meniscus was first described by RB Young in 1889.

The disc meniscus or its system is congenital, sometimes on both sides. The assumption that the disc meniscus does not develop into a sickle from the embryologically created disc shape has been invalidated by histological examinations on embryos. No disc meniscus shapes could be detected during the entire embryonic period, so that rather mechanical incorrect loads of menisci with greater variability are responsible for the formation of disc menisci. Discomfort (symptoms) only arise from a disc meniscus when the central area of the meniscus between the thigh roll (femoral condyle) and the tibial plateau (tibial head) is pinched and moved when the knee joint is under load , causing a classic snap phenomenon and pain. Due to the height and weight of children, these symptoms do not begin until around the age of 6 to 8. In very few cases the symptoms appear much earlier, but rarely only after the age of 12. The delayed recognition of typical disc meniscus complaints is often the result of the rarity and thus the ignorance of many doctors about the disease and its signs. The magnetic resonance tomographic examination is particularly suitable for reliable detection . Treatment is only indicated in the event of symptoms and consists of a partial removal of the disc meniscus.

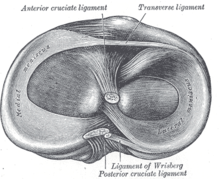

The normal meniscus

The two normal menisci of a knee joint run as triangular fiber cartilage discs inside and outside in the main joint between the thigh rollers and the tibial plateau as an elastic pressure pad with a base on the joint capsule . The articular surfaces of the femoral rollers and the tibial head are not congruent, i. H. they do not touch over a large area, but only selectively. This incongruence of the articular surfaces in the knee joint is compensated for by the menisci. When the joint is loaded, the meniscus surface absorbs a substantial part of the load in the edge areas and passes it on to the opposite joint surface. As a result, the forces acting on the articular cartilage surfaces are distributed over much larger areas and thus relatively reduced. This cartilage-protecting effect of the normal meniscus becomes clear when a meniscus is surgically removed due to an illness or injury. After a short period of time, the articular cartilage is damaged by excessive strain, including osteoarthritis .

Anatomy and structure of the disc meniscus

A generally recognized classification of the variations of the lateral meniscus, the Watanabe classification, contributes to a better understanding of the clinical picture of the disc meniscus. Disc menisci of types 1 and 2 have the same position within the knee joint as normal menisci, i.e. they are connected to their base at the joint capsule. However, their shape is not triangular, but they have the shape of a complete or incomplete disc, which, due to its position, completely separates the two joint surfaces of the bones involved - similar to a discus articularis , in English-speaking countries therefore called discoid meniscus . In principle, this means that the joint surfaces are very well protected against cartilage wear, as long as the disc meniscus itself does not cause any symptoms. Type 3 disc menisci (Wrisberg variant) are essentially not characterized by their shape or thickness, but by their lack of fixation on the posterior joint capsule. Snapping phenomena are therefore to be expected here particularly frequently.

Disc menisci are predominantly found in the lateral main joint of the knee, i.e. between the lateral thigh roll and the tibial plateau. Disc menisci are also very rarely found in the inner (medial) joint space.

Disc menisci can fill a differently sized area of the joint area between the meniscus base and the center of the joint on the eminentia intercondylica . One speaks of complete (type 1) or incomplete disc meniscus (type 2), whereby the transition from a wide normal meniscus and a narrow disc meniscus can be clearly recognized by the fact that in the case of a disc meniscus the thigh roll in the main stress zone is not the opposite in the arthroscopic assessment Articular surface of the tibial plateau reached directly.

Disc menisci have an unstable attachment to the joint capsule in a high percentage (30 to 77%). A fundamental instability is the characteristic of the type 3 disc meniscus. The instability can be congenital or as a result of meniscus entrapment as a tear. Particularly unstable menisci therefore show an increased snapping phenomenon.

Disc menisci can differ not only in their extension, but also in their substance, i.e. H. differ in their thickness. There are narrow meniscus disks a few millimeters thick, but also disks more than 5 millimeters thick throughout.

Disc meniscus pathology

Due to its tissue composition as fiber cartilage , the disc meniscus, like the normal meniscus, can withstand high pressure and shear loads. However, as the patient's body weight increases, the meniscus adheres to the joint surface in the highly lubricious system of articular cartilage and synovial fluid . The cause is a compression effect of the body load, which is stronger than the sliding ability between the meniscus and the joint surface. This sticking of the meniscus and the loosening of this short-term adhesion leads to the typical snapping during joint movement. As the meniscus surface “bakes” onto the joint surfaces, the two surfaces of the meniscus are moved in opposite directions when the knee is bent and stretched, which leads to internal tearing and thus to wear of the fiber tissue.

If the shear movement continues, it can lead to superficial tears in the meniscus . The disc meniscus can also tear off like a normal meniscus at its base on the joint capsule. A torn disc meniscus, however, no longer lies smoothly on the cartilage-covered joint surfaces in the joint, but rolls up along the tears and thus leads to local overloading of the articular cartilage. Overload of the articular cartilage, regardless of the cause (increased body weight, joint stages after fracture, congenital or acquired leg axis defects, athletic overload, joint incongruence and ligament instability) lead to premature joint wear ( osteoarthritis ) in the long term . Children and adolescents, in whom disc menisci occur almost exclusively, also develop osteochondrosis dissecans foci as a result of the regional overload if the menisci are unstable and torn . The torn disc meniscus can also be wedged into the joint space like normal meniscuses and pull on its attachment to the joint capsule, which causes pain.

Incidence

The frequency of the disc meniscus is difficult to determine because of the high number of asymptomatic patients. The values range from 0.4 to 17 percent for the lateral side and 0.06 to 0.3 percent for the medial side. Other authors estimate the value at 1 to 3 percent of children and adolescents, with both knees affected in 10 to 20 percent of patients. In Asian countries the incidence is apparently higher than in the western world.

Diagnosis

Often the patients or their parents report a typical joint snap when climbing stairs or walking. Most of the time, this sign has progressively developed over the months and years leading up to the performance. There is no pronounced pain. Joint blockages with a stretch deficit can occur temporarily or permanently. When examining the patient, the snapping of the joint can be reproduced during the functional examination. However, many patients also suffer from unspecific load-dependent knee problems without any blockages. Joint effusions rarely occur . Due to the typically laterally arranged disc menisci, the symptoms are localized laterally at the level of the joint space.

X-ray examinations , like blood laboratory tests, do not bring any abnormal findings. Rarely, the lateral joint spaces can appear widened on normal x-ray exams. A reliable representation of disc menisci can be found in the context of a magnetic resonance imaging examination . Here the cartilage disc in its expansion and thickness as well as tears in the tissue and the normal fixation of the meniscus at its base can be shown.

therapy

Arthroscopic partial resection

Disc menisci, which are found by chance during a magnetic resonance examination for a different indication , are left in place and not treated, as they represent perfect cartilage protection.

Clinically conspicuous disc menisci that cause discomfort or an annoying snapping or even cause pain and damage to the articular cartilage due to internal tears in the tissue or in the case of complete tears of the menisci, must be addressed surgically . The aim of the operation, in addition to eliminating subjective complaints such as pain, snapping phenomena and functional disorders, is to avoid further joint damage and meniscus tears. Postponing the operation if there is an indication to do so increases the risk of joint damage over the long term. During the operation, the disc meniscus is incised from its central opening (at the eminentia intercondylaris ) and then partially removed as part of an arthroscopy . Partial resection of the disc meniscus is not easy: On the one hand, the lateral joint space, in which the disc meniscus is typically located, is naturally very narrow. On the other hand, the lateral joint gap cannot be widened by a “release” of the outer ligament (targeted partial tearing of the collateral ligament), as is standard with the inner ligament in the event of operational difficulties. The lateral joint space is also filled by the thick disc meniscus itself (see Fig.). Working with mechanical surgical instruments in the narrow joint space in children is technically demanding. Therefore, in addition to the corresponding hand instruments ( punch ), mostly motorized instruments (“ shavers ”), or laser instruments or electrical so-called ablators are often used for the partial removal of the menisci . However, the HF devices (high frequency devices) and the lasers may have deeper damaging effects on the remaining meniscus tissue, which is why the use of HF devices in particular should be cautious. Some clinics are now using open approaches to the disc meniscus instead of the arthroscopic technique. A reliable overview of the joint is decisive for the choice of the surgical procedure.

The surgical therapy of a torn and dislocated complete disc meniscus is particularly complex. Here, the meniscus located in the anterior recess must first be repositioned onto the tibial joint surface, then the central part of the meniscus must be partially resected, and then the posterior horn and the intermediate part on the capsule must be reattached. It is important that the popliteus hiatus, the point of passage of the popliteus tendon through the meniscus base, is not closed by the meniscus suture.

The partial resection should only be carried out sparingly up to the point at which the thigh roll with its main stress zone reaches the articular surface of the tibial plateau. Resection beyond this point is not recommended because the meniscus no longer protects the joint surface.

After the partial resection of the disc meniscus, a careful examination of the stability of the rest of the meniscus with regard to its fixation on the joint capsule is of the greatest importance. If there is evidence of anterior, lateral, or posterior instability, suture fixation of the meniscus tissue is necessary. It can be performed either by suturing from the inside out (inside-out) or by the so-called all-inside technique (without exposing the outside of the capsule), technically easier with arthroscopic sutures.

Open partial resection

Due to the narrow anatomy of the lateral joint space and the resulting poor clarity of the operating area in the knee joint, open surgical techniques have recently been described again, with which the disc meniscus can be removed under view with an open joint access. In the pre-arthroscopic era, this procedure was standard practice.

Complications

Due to the tightness of the lateral joint space and the filling of the joint space with the tissue of the disc meniscus, superficial cartilage damage to the thigh roll and the tibial plateau is difficult to avoid during surgical therapy. With the use of electrical ablation processes or the laser, this damage can be kept lower and can be compensated by the body's own repair. In some cases, however, damage to the lateral femoral condyle (thigh roll) occurs - possibly also due to the changed damping situation after partial meniscus resection - that resembles an osteochondrosis dissecans (OD). B. During exercise and in the MRI image, signs of subchondral (located under the cartilage) necrosis of the bone tissue. This damage can heal if the affected leg is relieved. Sometimes, however, surgical therapy is also indicated.

Aftercare

After arthroscopy, partial relief on crutches is usually recommended for a few days , until the joint cartilage has normalized its water content, which was increased by the arthroscopy. The joint is then stabilized in the stretched position for about two to three weeks using a Velcro rail and can be loaded. As a result, the sparingly trimmed meniscus is further shaped by the femoral condyle roller, flattened at the edges and pushed into place. This stretching position must be maintained, especially with additional suture fixation of unstable meniscus parts, in order to allow the meniscus to heal on the capsule. In the following period, free movement and exercise are allowed, but sports are usually prohibited for two to six months. If symptoms reappear after surgical therapy, an MRI scan can often show changes that correspond to osteochondrosis dissecans and how these must be treated.

literature

- CR Good, DW Green, MH Griffith, AW Valen, RF Widmann, SA Rodeo: Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic discoid meniscus in children: classification, technique, and results. In: Arthroscopy , 2007; 23, pp. 157-163. PMID 17276223

- EB Kaplan: Discoid lateral meniscus of the knee joint. Nature, mechanism, and operative treatment. In: J Bone Joint Surg Am. , 1957, 39, pp. 77-87. PMID 13385265

- T. Barthel, R. Pesch, MJ Lippert a. a .: Arthroscopic treatment of the lateral disc meniscus. In: Arthoskopie , 1995, 8, pp. 12-18.

- H. Ikeuchi: Arthroscopic treatment of the discoid lateral meniscus. Technique and long-term results. In: Clin Orthop. , 1982, 167, pp. 19-28. PMID 6896480

- JC Ihn, SJ Kim, ICH Park: In vitro study of contact area and pressure distribution in the human knee after partial and complete meniscectomy. In: Int Orthop. , 1993, 17, pp. 214-218.

- I. Smillie: The congenital discoid meniscus. In: J Bone Joint Surg Br. , 1948, 30, pp. 671-682. PMID 18894619

- P. Aglietti, FA Bertini, R. Buzzi et al. a .: Arthroscopic meniscectomy for discoid lateral meniscus in children and adolescents: 10-year followup. In: Am J Knee Surg. , 1999, 12, pp. 83-87. PMID 10323498

- Hiroshi Mizuta, Eiichi Nakamura, Yutaka Otsuka, Satoshi Kudo, Katsumasa Takagi: Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Lateral Femoral Condyle Following Total Resection of the Discoid Lateral Meniscus. In: Arthroscopy , Vol 17, No 6 (July-August), 2001, pp. 608-612. PMID 11447548

- Fabian Goetz Krause, Ulrich Haupt, Kai Ziebarth, Theddy Slongo: Mini-Arthrotomy for Lateral Discoid Menisci in Children. In: J Pediatr Orthop. , Volume 29, Number 2, March 2009, pp. 130-136. PMID 19352237

- F. Franceschi, UG Longo, L. Ruzzini, P. Simoni, BB Zobel, V. Denaro: Bilateral complete discoid medial meniscus combined with posterior cyst formation. In: Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy , 2007, 15 (3), pp. 266-268. PMID 16917782

Further reading in free full text

- JG Cha u. a .: Anomalous insertion of the medial meniscus into the anterior cruciate ligament: the MR appearance. In: Br J Radiol. , 81, 2008, pp. 20-24. PMID 17971476

- Y. Lu et al. a .: Torn discoid lateral meniscus treated with arthroscopic meniscectomy: observations in 62 knees. In: Chinese Medical Journal (English), 120, 2007, pp. 211-215. PMID 17355823

- D. Davidson et al. a .: Discoid meniscus in children: treatment and outcome. (PDF) In: Can J Surg. , 46, 2003, pp. 350-358.

- KN Ryu et al. a .: MR imaging of tears of discoid lateral menisci. (PDF) In: AJR Am J Roentgenol. , 171, 1998, pp. 963-967. PMID 9762976

Individual evidence

- ^ RB Young: The external semilunar cartilage as a complete disc. In: J. Cleland et al. a. (Ed.): Memoirs and Memoranda in Anatomy. Williams and Norgate, London 1889, p. 179.

- ^ F. Adam: Orthopedics and orthopedic surgery. Knee. D. Kohn (Ed.). Georg Thieme Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-13-126231-1 , limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ EB Kaplan: Discoid lateral meniscus of the knee joint; nature, mechanism, and operative treatment In: J Bone Joint Surg Am , 1957, 39-A, pp. 77-87.

- ↑ MJ Kaplan: discoid lateral meniscus of the knee joint: nature, mechanism, and operative treatment. In: J Bone Joint Surg Am. , 1957, 39, pp. 77-87.

- ↑ JT Andrish: Meniscal injuries in children and adolescents: diagnosis and management. In: Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons , 1996, 4, pp. 231-237.

- ↑ PE Greis u. a .: Meniscal injury: I. Basic science and evaluation. In: J Am Acad Orthop Surg. , 10, 2002, pp. 168-176. PMID 12041938 .

- ^ H. Ikeuchi: Arthroscopic treatment of the discoid lateral meniscus. Technique and long-term results. In: Clin Orthop Relat Res. , 167, 1982, pp. 19-28. PMID 6896480

- ^ PA Nathan, SC Cole: Discoid meniscus. A clinical and pathologic study. In: Clin Orthop Relat Res. 64, 1967, pp. 107-113. PMID 5793003

- ↑ CL Jeannopoulos: Observations on discoid menisci. In: J Bone Joint Surg Am. 32, 1950, pp. 649-652. PMID 15428488

- ↑ JM Dickason et al. a .: A series of ten discoid medial menisci. In: Clin Orthop Relat Res. , 168, 1982, pp. 75-79. PMID 6896680

- ↑ a b M. Yaniv, N. Blumberg: The discoid meniscus. In: Journal of children's orthopedics , Volume 1, Number 2, July 2007, pp. 89-96, doi: 10.1007 / s11832-007-0029-1 , PMID 19308479 , PMC 2656711 (free full text).

- ↑ ES Hart u. a .: Discoid lateral meniscus in children. In: Orthop Nurs. , 27, 2008, pp. 174-179. PMID 18521032 .

- ↑ M. Jordan: Lateral meniscal variants: evaluation and treatment. In: J Am Acad Orthop Surg. , 4, 1996, pp. 191-200. PMID 10795054

- ^ SC Dickhaut, JC DeLee: The discoid lateral meniscus syndrome. In: J Bone Joint Surg Am. , 64, 1982, pp. 1068-1073. PMID 7118974

- ↑ M. Jordan et al. a .: Discoid lateral meniscus: a review. In: South Orthop J. , 2, 1993, pp. 239-253.

- ^ MS and LJ Micheli: The pediatric knee: evaluation and treatment. In: JN Insall, WN Scott (Ed.): Surgery of the kne . 3. Edition. Churchill-Livingstone, 2001, ISBN 0-443-06545-4 , pp. 1356-1397.

- ^ FG Krause, U. Haupt, K. Ziebarth, T. Slongo: Mini-Arthrotomy for Lateral Discoid Menisci in Children. In: J pediatr orthop. 2009; 29, pp. 130-136.