Swiss troops in the service of Lucchese

The Federal Guard was the only Swiss force in the service of Lucchese .

From 1653 to 1806 it had to guard the Palazzo Ducale (ducal palace = city palace) and later also the Ufficio dell'Abbondanza (city treasury) and defend it if necessary.

Swiss troops in foreign service was the name of the paid service of commanded, whole troop bodies abroad, regulated by the authorities of the Swiss Confederation by international treaties . These treaties contained a chapter regulating military affairs: the so-called surrender (or private surrender if one of the contracting parties was a private military contractor).

Brief history of Lucca

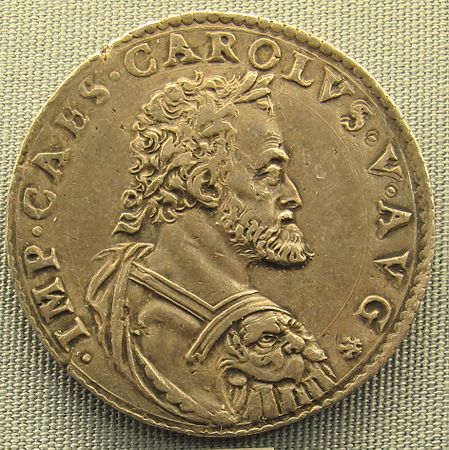

Lucca , as the former ducal seat of the Lombards and an independent city-state on the Franconian pilgrimage to Rome, reached its heyday in the 11th to 14th centuries with banking and silk trading. In the competition with its neighboring republics Pisa and Florence , Lucca ultimately remained insignificant, while Florence conquered the rest of Tuscany. In the 16th century, when the Medici and Florence threatened to overpower, Lucca allied itself with Spain's Charles V in 1521 , built the still imposing city wall and remained independent. Only Napoleon put an end to the city-state. It then came under the rule of the Bourbons and shortly before the Italian unification in 1861 under the Grand Duchy of Tuscany .

The uprising of the silk weavers

In 1532, when a riot among the silk weavers startled the city leaders, the Consiglio Generale degli Anziani (Grand Council) decided to protect the Palazzo Ducale and its authorities with a palace guard. Initially recruited from the citizens of Lucca and later from young nobles from countries not directly neighboring, banned for honorary trafficking or for political reasons, it was replaced by a disciplined Swiss troop in the middle of the 17th century after a few brawls with a bloody outcome.

The Federal Guard

| Name, duration of use |

(1 luc ) Federal Guard 1653–1806 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year, contractual partner |

1653: Surrender of 26 sides of the Republic of Lucca, represented by the Consiglio Generale degli Anziani (Grand Council) and the Gonfaloniere della Giustizia (“Standard bearer of justice / justice”, de jure head of state of the republic and commander-in-chief of the armed forces), with the magistrate and the great Council of the Republic of the City and Canton of Lucerne. The surrender also contained regulations with 26 articles. Draconian threats of punishment did not necessarily show the good reputation of the Swiss mercenaries, for example:

Lucca undertook to provide a confessor and a free surgeon (doctor). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stock, formation |

1 company of 64 men;

Target stock of the unit:

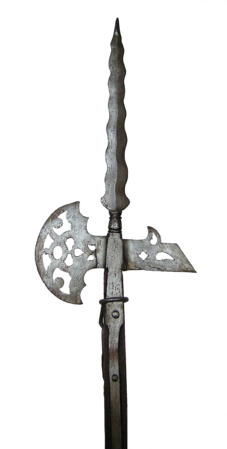

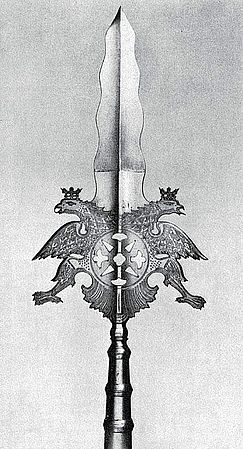

Partisans , pikes , halberds and arquebuses served as armament . |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner, commander, namesake |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin squad, troop |

From the Catholic places of the Confederation, especially from Lucerne. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use, events |

In 1662 the Consiglio Generale transferred the supervision of the guard to the Gonfalionere. For him, the supreme Anziano (supreme executive councilor), four men of the guard always had to be available, at least one of whom had to speak the Italian language.

The main task of the guards was the constant watch at the gate, the guarding of the Palazzo Ducale, but at most its defense. At the meetings of the Consiglio Generale, his appearances in public and at the numerous church festivals, the guard had to represent in their blue gala uniforms in honorary service. It was also worn at the two-month solemn oath renewal ceremony. In 1750 the guarding of the Ufficio dell'Abbondanza (literally: Office for Abundance, the city treasury) was added to the area of responsibility. The commandant and his staff were recruited from the patriciate and citizens of the city of Lucerne, to whose council all applications for the guard had to be submitted. This came more and more city dwellers, then back - and Beisässen , finally country were sitting in the city and, ultimately, most residents of the upper Freiamt to train. The service in Lucca was obviously in great demand. Candidates were prepared to pay a "recognition" (tip), which was distributed to the staff members, graduated according to rank. Some even took over promissory notes from their predecessors. Occasionally, social cases and debt-makers (including officers), people of dubious reputation or even criminals were deported into the guard (with the seizure of a portion of their wages). The Anziano di Buona Guardia (the councilor responsible for security) could, however, reject applicants if they did not meet his requirements. In 1662, and again in 1670, he rejected Lucerne's suggestion for the promotion of Ensign Hans Balthasar Kündig to lieutenant of the guard because of lack of war experience (a condition for surrender). A guard court, consisting of members of the staff and the team, had to deal with disciplinary cases. His judgments could be softened or tightened by the municipal authorities in Lucca (but not as a galley or death penalty). There does not seem to have been any tongue mutilation due to cursing. On the other hand, to death sentences for desertion. However, they were only carried out symbolically: a metal plaque with the name of the convict was hung on the gallows. Many of those punished enjoyed protection, as, for example, a Fridli Mühlebach wrote in 1708:

What prompted Lieutenant Fleckenstein to comment in 1740:

Each guardsman had his own room in a wing of the Palazzo Ducale and his own wine barrel in the cellar (!). To a certain extent, he could even practice his trade as a tailor, shoemaker or carpenter as a side income and, if there was a lot of work, he could have his guard duty done by a comrade. When sons from mixed marriages with Lucchese women began to apply more and more applications from 1690, these "half-whelps" apparently represented a challenge for the councils on both sides. When the guards' families grew to over 200 members, countermeasures were taken. In spite of a twenty-year ban for guardsmen, which was not strictly enforced, several "dynasties" emerged, such as the Holzmann and Greter from Buchrain, the Meyer from Stattenbach or the Thürig from Malters. Not all lieutenants had a lucky hand: Even the first guard commander, Martin AnderAllmend, got into debt because of outstanding wages from his previous service in Naples, exaggerated the influence of the guard court. Exclusions from the Guard for disciplinary reasons led to new entries with the welcome "recognition". He was deposed in 1662. The long-serving lieutenant Johann Jakob Wagner escaped the same fate in 1691 only through his resignation. Even Lieutenant Joseph Anton Franz Xaver von Fleckenstein could not get rid of his mountain of debt, despite a massive increase in "recognition". When 44 guardsmen threatened to leave and the existence of the guard was at stake, he was forced to resign in 1769 after 33 years of service. The federal guard of Lucca was not lifted until 1806 by Elisa Baciocchi , sister of Napoleon Bonaparte, who became Princess of Lucca and Piombino and Grand Duchess of Tuscany after the French invasion in 1792 . |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

bibliography

- Joseph Schürmann: List of officers and men in the Swiss Guard in Lucca, 1653–1792. State Archives, Lucerne 1982.

- Kurt Messmer, Peter Hoppe: Lucerne patriciate, social and economic history studies on the origin and development in the 16th and 17th centuries. Lucerne Historical Publications, Volume 5, edited by the State Archives of the Canton of Lucerne, editor: Anton Gössi. Rex-Verlag, Lucerne 1976.

See also

Web links

- The city wall of Lucca (English)

- Ducal Palace in Lucca (Italian)

- Homepage Ducal Palace in Lucca (Italian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Schürmann: List of officers and men of the Swiss Guard in Lucca, 1653–1792. 1982

- ↑ Guardia Svizzera ( Memento from August 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ State Archives Lucerne ACT 13

- ↑ State Archives Lucerne ACT 13/1114

- ↑ Ducatone di Milano: large silver coin, minted for the first time in Milan in 1551 by Charles V , distributed in large quantities

- ↑ Gregor Egloff: Ander Allmend (Allmender). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ a b c d e Markus Lischer: Fleckenstein (from). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Gregor Egloff: Kündig. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Markus Lischer: Mayr von Baldegg (Meyer von Baldegg). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ State Archives Lucerne ACT 13/1115 ff.

- ^ André Holenstein: Hintersassen. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Peter Walliser: Beisassen. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ André Holenstein: Landsassen. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .