Self-commitment

Even bond ( "self commitment" ), in game-theoretic sense, is a supportive or concomitant action of a strategic campaign . It is an obligation to which an actor is bound for a long time. Self-commitment shows the opponent that the intention to carry out an action really exists because taking back the move is too expensive or even impossible. The actor commits himself to an action by creating circumstances that force him from outside to stick to his decision. The result of a game can thus be decisively influenced. Self-commitment means giving up your own freedom of action. This way, behavior can be signaled to the opponent that would otherwise be implausible.

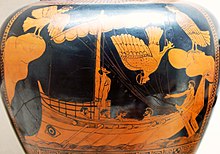

If the self-commitment takes place without external opponents, one also speaks of a commitment device (German: “binding self-commitment” or just “self-commitment”). This restricts the freedom of action with a short-term horizon in favor of a longer-term desired result that would not come about without corresponding self-commitment. In this sense, self-attachment is a remedy for akrasia . The classic example of a commitment device is Odysseus , who lets himself be tied to the mast in order to withstand the beguiling singing of the sirens . He orders his crew to cover their ears with wax so that they neither hear the sirens nor his requests to be untied.

Assignment

Self-commitment is the part of strategic moves that makes the actual action plan credible . The aim of self-commitment is to influence the behavior of the opponent for your own benefit. In corporate strategic decisions, self-commitment is an essential prerequisite for gaining competitive advantages . For example, it enables companies to create barriers to market entry and maintain them for a certain period of time. Possibilities for self-commitment in the entrepreneurial area include, for example, investments in research and development, investments in production capacities, decisions about the capital structure and the transfer of decision-making power to various bodies. Self-commitment can only take place in a dynamic environment, i.e. when playing games with a time structure. This means that from a game theory point of view, at least two decision points must be considered. This also means that self-commitment must be observable and understandable, otherwise it will not be recognized by the opponent and cannot influence him in his later decisions. The credibility is achieved through irreversibility in the form of strong binding forces. Even the irreversibility of time creates the irreversibility of a decision, so that, for example, investments in research and development once spent cannot be reversed.

Combination of self-commitment options

Using the example of Heinrich V , a combination of different possibilities of self-commitment can be illustrated. Heinrich V was particularly good at motivating his troops and thereby increasing the credibility of his strategic move . Before the Battle of Agincourt he said to his soldiers: “He who has no courage for this fight [can] return; his passport is to be issued and kroner to be stuck in his purse for escort: we do not wish to die in the company of the man who fears that his comradeship might die with us. ” This type of self-commitment combined various points: peer pressure and pride caused it Soldiers do not accept this offer. But with the rejection there was no turning back. In a psychological sense, they broke the bridges behind them. This implied a contract to fight, which could also mean death.

Answer rules

Self- binding can be modeled in game theory by an answer rule in which an answer is determined in advance for the move of the other. Your own actions follow that of the other depending on the opponent's move. This is a sequential game , regardless of which strategic move is being made. Even a simultaneous game , in which you commit yourself through a self-commitment in the form of an answer rule, is converted into a game with sequential moves. For example, an answer rule occurs when parents say to their child, “There will be no TV unless you tidy your room.” The answer will be clearly and unambiguously determined before the child cleans up their room. The action of the parents, which is defined in the answer rule, follows the action of the child. The child should be punished for not tidying up the room. It thus receives an incentive to act in accordance with the parents' wish, which can be interpreted as a strategic advantage for the parents. Answer rules can be defined in the form of threats or promises . For example, in the case of an airplane hijacking, it is a threat if the terrorists set the response rule to kill all passengers if their demands are not met. Self-binding through a promise can occur, for example, if the public prosecutor promises the accused a lighter sentence if he testifies against his co-defendant.

Further examples

Historically, it was customary to hold hostages when resolving conflicts in order to bind yourself to a peace treaty. One example is Ottokar I Přemysl, who hosted Philip of Swabia in exchange for his royal dignity.

The example of the Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés , who successfully fought against the Aztecs in 1518 , illustrates the effect of self-attachment. Cortés ordered his troops to burn their own ships, thereby destroying the possibility of retreat. The troops had to win the battles to survive.

In the so-called Chicken Game , a driver can create a self-commitment by z. B. throws his steering wheel out of the window. In doing so, he makes his opponent believable that he will definitely not evade.

literature

- Gharad Bryan, Dean S. Karlan, Scott Nelson: Commitment Devices . In: Annual Review of Economics . Vol. 2 (September 2010), doi : 10.1146 / annurev.economics.102308.124324 , pp. 671-698. (Online as a preliminary version (PDF; 244 kB) from April 25, 2010.)

- Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners: Strategic Know-How for Winners . Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 978-3-7910-1239-1 .

- Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership . Gabler, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8349-1178-0 .

- Volker Bieta, Wilfried Siebe: Game theory for executives . Ueberreuter, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-7064-0409-5 .

Web links

- How To Do What You Want: Akrasia and Self-Binding , article by Daniel Reeves, January 24, 2011.

- Commitment Problems and Devices on EconPort

- Save Me From Myself , Freakonomics - Contribution by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner. (February 2012)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 141.

- ↑ Cf. Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership, p. 13.

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 121.

- ↑ Cf. Volker Bieta, Wilfried Siebe: Game Theory for Managers p. 224.

- ↑ See Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership, p. 7.

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 122.

- ↑ See Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership, p. 7.

- ↑ See Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership, p. 21.

- ↑ See Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership, p. 54.

- ↑ Cf. Clemens Löffler: Strategic Self-Commitment and the Effects of Time Leadership, p. 55.

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 159.

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 122.

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 125.

- ↑ See Avinash K. Dixit , Barry J. Nalebuff: Game Theory for Beginners, p. 122 f.

- ↑ See Clemens Löffler: Strategic self-commitment and the effects of time leadership, p. 20.

- ↑ Cf. Clemens Löffler: Strategic Self-Commitment and the Effects of Time Leadership, p. 55.