Sinotibetan divination calculations

The Sinotibetan divination calculations ( Tibetan : nag rtsis ) were the most important fortune-telling method in Tibet , which was especially important for marriage, death, illness, childbirth and for the annual forecast of the future. In the following they are called Nag-rtsis , they are a sub-discipline of the Tibetan calculation science (Tibetan: rtsis ).

The Nag-rtsis was based on the five-element teaching of Chinese origin , which is based on harmonious or antagonistic relationships between the five elements fire, water, wood, earth and iron, which make up time and space.

The divination nag-rtsis is to be distinguished from the Tibetan astrology . This represents a further discipline within the Tibetan calculation science and comes from India.

The teachings of the Nag-rtsis came to Tibet from China in the time of the Yar-lung dynasty (7th - 9th centuries AD), received an independent further development in Tibet and developed their full meaning in the 17th century under the 5th The Dalai Lama and his regent Sanggye Gyatsho .

Definition

In the past, the term Nag-rtsis was often translated as “black arithmetic” by western Tibet researchers and was associated with the opposite term dKar-rtsis “white arithmetic”. This gave the impression that Nag-rtsis was assigned to the area of black magic, while "white arithmetic" was assigned to Buddhism.

In fact, the term Nag-rtsis is an abbreviation for rGya-nag gi rtsis "Chinese calculation (science)". As a rule, the Nag-rtsis should be strictly distinguished from the Chinese astronomy and astrology called rGya-rtsis, which was also known in Tibet.

dKar-rtsis "white calculation", however, was a misspelling for sKar-rtsis "calculation of the star (place) e", which was used to describe Tibetan astronomy .

The science called Nag-rtsis is also known as "calculation of the elements" ('byung-rtsis).

Basics

According to the Nag-rtsis, time and space, which are always understood as “time in the life of a person” or “space related to persons”, are composed of the five elements mentioned in the introduction.

As a result, one or more elements are assigned to all components of time recorded in the Tibetan calendar , i.e. the year, month, day and time of day and the components of space (cardinal points). The same applies to celestial phenomena such as planets and lunar houses , and to other special forces that determine life from Chinese ideas, such as B. the nine numbers of the magic square (sme-ba dgu) and the eight triagrams (tib .: spar-kha, chin .: bagua).

It is assumed that the course of a person's life is determined by certain basic aspects or basic life interests. These are:

- "Material prosperity" or prosperity (dbang-thang) of a person.

- This concerns vital interests, which can be explained using the following questions:

- Will the livestock increase or will the four herds be swept away by epidemics?

- Can commercial transactions be carried out successfully?

- Will Someone Have Many Children?

- Will my home be destroyed by earthquakes or floods?

- This concerns vital interests, which can be explained using the following questions:

- "Health" or physical condition (lus).

- This concerns vital interests, which can be explained using the following questions:

- Is the general state of health good?

- Will you get sick?

- This concerns vital interests, which can be explained using the following questions:

- Lifespan, life force (srog).

- This concerns vital interests, which can be explained using the following questions:

- What is the life expectancy?

- Can sudden death happen?

- This concerns vital interests, which can be explained using the following questions:

- Luck or bad luck (klung-rta).

- This concerns vital interests, which can be exemplified by the following question:

- Will the ventures (war, trade, gambling) have a happy ending?

- This concerns vital interests, which can be exemplified by the following question:

The five elements fire, water, wood, earth and iron have positive, neutral or negative relationships with one another. These relations are called mother (ma), son (bu), enemy (dgra), friend (grogs) and self-relation. For example the element water is the "enemy" of the element "fire". Here there is a relation that has certain negative effects in relation to the element “fire” if it meets the element “water”. Conversely, the element “fire” is the “friend” of the element “water”. There is a relation here that has certain positive effects in relation to the element “water” if it meets the element “fire”. The self-relation occurs when an element meets itself. The calculation of such relations, their evaluation and prognostic interpretation form the core of Nag-rtsis.

Simple example

If someone was born in 1942, this year corresponds to the Earth-Horse year according to the sixty-year cycle of Nag-rtsis. For the elements that are assigned to a person with this year, the following is calculated:

- Material prosperity: earth

- Health: fire

- Life force: fire

- Good luck or bad luck: iron

The elements for the month, day and time of day of the birth are calculated accordingly. These are then determining factors that accompany a person throughout life.

When this person reaches the sixth year of life, this is the water-pig year according to the sixty-year cycle. The following elements are calculated for this.

- Material prosperity: water

- Health: water

- Life force: water

- Good luck or bad luck: fire

These elements of the current year are now related to the corresponding elements of the year of birth, which results in the following:

- Material prosperity: water has the relation "friend" to earth

- Health: Water has the relation "enemy" to fire

- Life force: water has the relation "enemy" to fire

- Luck or bad luck: fire has the relation "enemy" to iron

According to a given key, the divination master now places black and white stones in a row in front of him on a cloth. For example, he puts down two black stones for the relation “enemy”. In the above case, this results in a row of stones consisting of six black stones and two white stones.

The divination master now consults other texts, called “Explanation of Fruits”, which explain what this means for the course of the sixth year of life and which rituals are to be carried out in order to avoid predicted misfortunes.

History of the Nag-rtsis

Origin of Nag-rtsis

According to Tibetan historiography, the Nag-rtsis, like almost all important Tibetan sciences, has a transcendent origin.

The Nag-rtsis was conveyed by the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī on the Wutai Shan to a circle of divine listeners, the four-faced Indian god Brahma , the king of serpent spirits ( Nāga ), the goddess Vijayā and a mythical Brahmin by the name of Ser-skya duration.

The group of these listeners was joined by the four so-called magicians ('phrul-mi bzhi), to whom, in addition to the mythical Chinese emperors, Vangthe (Tib .: vang the, Chin .: Huangdi ), Jinong (Tib .: ji nong, Chin. : Shennong ) and Jikong (tib .: ji kong, chin .: Ji Gongsheng 姬 宮 湦) of the western Zhou dynasty also belonged to Confucius (tib .: kong tse).

Ultimately, this audience was supplemented by four human persons who received the Nag-rtsis teachings for transmission to the people.

History of tradition in Tibet

The presentation of the history of Nag-rtsis knows three periods of translation of Chinese works into Tibetan: early translation period (snga-'gyur), medium translation period (bar-'gyur) and late translation period (phyi-'gyur).

The first two periods of this fall during the Tibetan royal period (7th - 9th centuries AD). The outstanding figure in these two translation periods was a Chinese scholar, who is mentioned in the sources as Duhar Nagpo (Tib .: du har nag po ) (8th century). His most famous work, Rin-chen gsal-sgron (“Precious clear lamp”), has unfortunately not emerged to this day.

The works of the first two translation periods, many of the titles of which have come down to us by name, were apparently largely lost in the political turmoil of the late 9th and 10th centuries AD.

The last period of translation of Nag-rtsis works, which, analogous to the translation of Buddhist works from Sanskrit, was also called the late translation period (phyi-'gyur), began at the end of the 10th and 11th centuries AD . Its leading representative was the Tibetan Khampa Thramo (Tib .: khams pa khra mo ), who presented a large collection of translations from Chinese under the title Yang-'gyur gsal-sgron ("Newly translated clear lamp"). In addition to numerous texts that were ascribed to the Revelation of Mañjuśrī, this work also contained many writings that Duhar Nagpo is said to have written. This compilation is also not accessible to this day.

Further development in Tibet

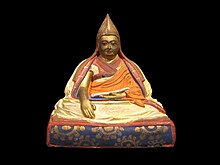

One of the great teachers of the Nag-rtsis of the Tibetan Middle Ages is the Kyungnag (Tib .: khyung nag ) ("Black Garuda ") Shakya Dar (Tib .: sha kya dar ) (approx. 13th century) Teaching tradition in particular the work of the regent Desi Sanggye Gyatsho (Tib .: sde srid sangs rgyas rgya-mtsho ) (1653–1705) is based.

Until the 17th century, the Nag-rtsis was practiced almost without exception by the followers of the so-called old school ( Nyingmapa ) of Tibetan Buddhism and the followers of the Bon religion. The clergy of the so-called "new schools of Tibetan Buddhism" ( Sarma ) ignored the Nag-rtsis almost completely because they believed that they were essentially non-Buddhist.

The great dissemination and popularity of the Nag-rtsis' teachings and practices among the broad, common people of Tibet was ultimately the main reason that the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1685) and his regent Desi Sanggye Gyatsho used the Nag-rtsis as a way recognized for attaining Buddhahood. Most of the work of the regent Desi Sanggye Gyatsho, known as " White Beryl " (Sanskrit / Tibetan: Vaiḍūrya dkar po ), is dedicated to Nag-rtsis.

As a result, Nag-rtsis was fully recognized within the Gelugpa School.

This then also applied to the other schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The well-known Eastern Tibetan encyclopaedist Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye (Tib .: ´jam mgon kong-sprul blo-gros mtha'-yas ) (1813–1899) was an excellent expert on Nag-rtsis, about whose content he also presented several publications.

Essential content

The main subject areas of Nag-rtsis treatises from the 17th century onwards are as follows:

- (keg-rtsis) Calculations for predicting the future of accidents that can happen to a person in the course of a year.

- (tshe-rtsis) Calculations for predicting the future over the course of a person's entire life.

- (bag-rtsis) Marriage calculations. The most important issue here is the question of whether the people selected for marriage are allowed to marry at all.

- (nad-rtsis) Calculations for predicting the future of diseases and determining the causes of diseases.

- (gshin-rtsis) Calculations on the death of a person. This includes identifying the causes of death and predicting rebirth in the next life.

- (byes-'gro'i rtsis) travel calculations. These are predictions about whether you should take a trip at all and what dangers you will encounter on the way.

Related disciplines

Tibetan geomancy , which primarily originates from China, but also contains significant Indian elements, and the gTo rituals , which are also largely based on Chinese ritual practices, were connected with the Nag-rtsis . The latter were mostly practiced to ward off calamities, which had been predicted by the calculations of the Nag-rtsis.

The gTo rituals were considered secret until the 19th century because they contained practices that were completely incompatible with Buddhist teachings in their effects. In this respect, it is considered spectacular that the Eastern Tibetan scholar Mi-pham rNam-rgyal and the encyclopedist Kong-sprul Blo-gros mtha'-yas published extensively on these ritual practices.

Philosophical evaluation

The basic idea of Nag-rtsis is the idea that not only does the physical world consist of these five elements, which are mutually dynamic, but that time is also built up from these elements. According to this, time is not an impersonal continuum divided into abstract units of measurement, but a network of relationships between elements of the past, present and future which, when they come together as the present, significantly influence the individual's being in the world and his relationships with other people. In other words, the theory of the elements brings together the physical and the living world over time to form a whole that determines existence.

literature

Essays

- Dieter Schuh: About the possibility of identifying Tibetan dates using the sMe-ba dgu . In: Central Asian Studies of the Department of Linguistics and Cultural Studies in Central Asia at the University of Bonn , Vol. 6 (1972), pp. 485–504, ISSN 0514-857X .

- Dieter Schuh: The explanations of the 5th Dalai Lama Ngag-dbang blo-bzang rgya-mtsho on the calculation of the nine sMe-ba . In: Central Asian Studies of the Department of Linguistics and Cultural Studies in Central Asia at the University of Bonn , Vol. 7 (1973), pp. 285–299, ISSN 0514-857X .

- Dieter Schuh: The Chinese stone circle. A contribution to the knowledge of the Sino-Tibetan divination calculations . In: Central Asian Studies of the Department of Linguistics and Cultural Studies of Central Asia at the University of Bonn , Vol. 7 (1973), pp. 353-423, ISSN 0514-857X .

Monographs

- Te-ming Tseng: Sino-Tibetan divination calculations (Nag-rtsis) presented using the work dPag-bsam ljon-šing by Blo-bzang tshul-khrims rgya-mtsho . International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies, Halle / Saale 2005, ISBN 3-88280-070-4 (contributions to Central Asian Studies ; 9).

- Shen Yu Lin: Mi pham's systematization of gTo rituals . International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies, Halle / Saale 2005, ISBN 3-88280-071-2 (contributions to Central Asian Studies ; 10).

- Gyurme Dorjee: Tibetan Elemental Divination Paintings. Illuminated manuscripts from The White Beryl od Sangs-rgyas rGya-mtsho with the Moonbeams treatise of Lo-chen Dharmaśrī . John Eskenazi Books, London 2002, ISBN 0-9539941-0-4 .