Extrasystole

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| I49.1 | Atrial extrasystole |

| I49.2 | AV-junctional extrasystole |

| I49.3 | Ventricular extrasystole |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

An extrasystole is a premature heartbeat (hence the English term "premature heart beat" for extrasystole) that occurs outside the physiological heart rhythm . As an irritation disorder, it is one of the cardiac arrhythmias . The actual rhythm can remain unaffected or be shifted. Most extrasystoles ( extrasystole ) do not arise in the normal pacemaker center ( sinus node ), but in ectopic excitation centers (ectopic focus) (from ancient Greek εκτοπία , ektopía , "extra-locality"; from εκτός , ektós "outside", and τόπος , tópos "place") . The person concerned often feels it as a palpitation . Extrasystoles not only occur in diseases of the heart, but can also be found in healthy people without heart damage. Occasionally, however, they can also indicate significant heart disease.

Depending on where they originate in the heart, a distinction is made between ventricular extrasystoles ( VES , originating in one of the heart chambers) and supraventricular extrasystoles ( SVES , originating mostly in one of the atria).

causes

Extrasystoles often occur in healthy people with no disease value, triggering factors can be excitation, fatigue, increased activity of the autonomic nervous system , drugs such as alcohol , nicotine or caffeine or an electrical accident . However, organic diseases of the heart are also possible triggers, especially coronary heart disease , but also cardiomyopathies or inflammation of the heart muscle ( myocarditis ). Furthermore, causes outside the heart can lead to extrasystoles. These include an excess of thyroid hormones ( hyperthyroidism ), various medications, electrolyte disorders , blockages in the thoracic spine or Roemheld's syndrome .

to form

Supraventricular extrasystole

Supraventricular extrasystoles arise as premature beats from centers above the division (bifurcation) of the bundle of His , mostly in the atrium. They are divided into sinus extrasystoles , atrial extrasystoles ( atrial SVES ) with an ectopic center in the atrial myocardium, and atrioventricular extrasystoles ( nodal SVES ) with an ectopic center at the AV node , also called AV-junctional SVES . With atrial SVES, the sinus node is also discharged. As a result, its rhythm shifts exactly by the conduction time from the ectopic focus to the sinus node ( non- compensatory pause ). In the nodal extrasystole, the atrium is discharged backwards. Both can bring the heart chambers out of their rhythm (supraventricular arrhythmia). SVES in healthy individuals do not require any therapy; if a heart disease is present, this is given priority.

Ventricular extrasystole

In a ventricular premature beat ( Kammerextrasystole ) the excitement focus on the ventricles propagates from an airport in the ventricles (ventricular) ectopic out (located outside the normal pacemaker structures).

Symptoms

Ventricular extrasystoles ( PVCs ) can be perceived as a single failed heartbeat, a single stronger heartbeat or, in general, as palpitations . After a ventricular extrasystole, either the heart rhythm remains unaffected, since the next sinus excitation occurs after the extrasystolic refractory period of the ventricles (especially with low heart rates and early extrasystole), or there is a compensatory pause .

After exercise, extrasystoles can be accompanied by chest pain, fainting or weakness, and drowsiness. Symptoms can worsen under stress.

Fear reactions, for example in the context of cardiophobia , can also cause sweating, tachycardia, fear of death, increased blood pressure, nausea, dizziness, shortness of breath, hyperventilation and other reactions of the autonomic nervous system .

In most patients, ventricular extrasystoles go unnoticed and without symptoms.

causes

Ventricular extrasystoles can occur in healthy people of all ages. In most cases, they appear spontaneously with no apparent cause. When the autonomic nervous system is stimulated by stress, fear, drugs such as alcohol , caffeine , cocaine , exhaustion and lack of sleep, extrasystoles can increase. A low potassium or magnesium level and a high calcium level also favor their occurrence.

diagnosis

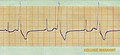

Extrasystoles can be felt on palpation of the pulse and the auscultation of the heart heard. Ventricular extrasystoles can be diagnosed using an EKG . A distinction is made between right ventricular and left ventricular extrasystoles. The incident extrasystoles have a widened QRS complex .

Several extrasystoles from one excitation center ( monotopic ) appear similarly ( monomorphic ) in the ECG . Polytopic extrasystoles, on the other hand, arise in different excitation centers and therefore also differ in the ECG ( polymorphic ). Extrasystoles occurring in pairs are referred to as couplets, and three extrasystoles following one another as triplet. If there are four to seven consecutive extrasystoles, one speaks of a volley, from eight consecutive ventricular beats of a ventricular tachycardia . In the more recent literature, more than three ventricular heart actions are referred to as non-sustained ventricular tachycardia ( nsVT ). If a PVC follows every normal excitation of the heart, one speaks of the bigeminus . If every second normal excitation of the heart is followed by a PVC, then one speaks of a trigeminal nerve.

The classification of the PVCs in heart patients was based on the Lown classification .

treatment

Isolated PVCs do not require treatment in healthy individuals, especially if they occur without cardiac symptoms. Treatment with a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker is indicated for cardiac symptoms . With high stress (more than 20,000 extrasystoles per day), regular check-ups of the ejection performance can be useful.

For heart patients, the treatment depends on the underlying heart disease.

In some cases, treatment with magnesium supplements can reduce the occurrence of extrasystoles.

Prevalence

PVCs are also common in healthy people. A study of 1165 healthy volunteers aged 18 to 45 found ventricular extrasystoles in 40.6% of the persons in a study period of 24 hours, couplets in 2.9% and a ventricular bigeminus in 0.4%. The prevalence of extrasystoles also increased with age. Under the age of 11, extrasystoles occur in 1% of people, and 69% of people in the 75-year-old age group. In a further study of 101 people with healthy heart , at least one ventricular extrasystoles occurred in 39 (38.6%) and at least 100 in 4 (4%) persons during a 24-hour ECG . Heart disease was excluded in all subjects by a chest x-ray, EKG, echocardiography, exercise test, cardiac catheter examination, and coronary angiogram. An investigation by the US Air Force with 122,043 male pilots and cadets revealed at least one ventricular extrasystole in 952 (0.78%) during the approx. 48-second ECG recording; the incidence increased with age.

literature

- Herbert Reindell , Helmut Klepzig: diseases of the heart and blood vessels. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition, ibid. 1961, pp. 450-598, here: pp. 562-566 ( Die Extrasystolen ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heiner Greten , Tim Greten, Franz Rinninger: Internal medicine . Georg Thieme Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-162183-2 ( google.com [accessed June 4, 2016]).

- ↑ Jochen Weil: Detection of arrhythmias: made easy. .

- ↑ a b B. Akdemir, H. Yarmohammadi, MC Alraies, WO Adkisson: Premature ventricular contractions: Reassure or refer? . In: Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine . 83, No. 7, July 1, 2016, pp. 524-530. doi : 10.3949 / ccjm.83a.15090 . PMID 27399865 .

- ^ Klaus Holldack, Klaus Gahl: Auscultation and percussion. Inspection and palpation. Thieme, Stuttgart 1955; 10th, revised edition, ibid 1986, ISBN 3-13-352410-0 , p. 203.

- ↑ Cristina Nádja M. Lima De Falco et al .: Late Outcome of a Randomized Study on Oral Magnesium for Premature Complexes (2014); 103 (6), pp. 468-475; doi: 10.5935 / abc.20140171

- ↑ Pooja Hingorani et al .: Arrhythmias Seen in Baseline 24 ‐ Hour Holter ECG Recordings in Healthy Normal Volunteers During Phase 1 Clinical Trials (2015); 56 (7), p. 885-893; doi: 10.1002 / jcph.679

- ^ Yong-Mei Cha, Glenn K. Lee, Kyle W. Klarich, Martha Grogan: Premature Ventricular Contraction-Induced Cardiomyopathy . In: Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology . 5, No. 1, February 2012, ISSN 1941-3149 , pp. 229-236. doi : 10.1161 / CIRCEP.111.963348 . PMID 22334430 .

- ^ JB Kostis, K. McCrone, AE Moreyra, S. Gotzoyannis, NM Aglitz, N. Natarajan, PT Kuo: Premature ventricular complexes in the absence of identifiable heart disease . In: Circulation . 63, No. 6, June 1981, pp. 1351-1356. doi : 10.1161 / 01.CIR.63.6.1351 . PMID 7226480 .

- ^ Roland G. Hiss, Lawrence E. Lamb: Electrocardiographic Findings in 122,043 Individuals . In: Circulation . 25, No. 6, June 1962, pp. 947-961. doi : 10.1161 / 01.CIR.25.6.947 . PMID 13907778 .