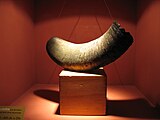

Drinking horn

A drinking horn is a drinking vessel that was already in use in antiquity , originally made from animal horns ( bison or aurochs ) and later reproduced in clay and metal by the Greeks at the time of refined culture. In some cultures a so-called rhyton was used at the same time , from which, in contrast to the normal drinking horn, people were drunk from the open tip and not from the large mouth.

Historical background

Probably the oldest illustration of a drinking horn is the Venus von Laussel , a limestone figure made in France around 25,000 years ago. Whether it is actually a drinking horn can no longer be determined today, as horns may also have served as a container for paint and food, but the gesture of the woman who brings the horn with the mouth to the face strongly suggests its use as a drinking vessel .

Archaeological evidence of the use of drinking horns, in the form of metal fittings and hanging fittings, dates back to the Bronze Age . An impressive collection of nine drinking horns studded with bronze and gold was placed in the grave of the so-called Celtic prince von Hochdorf . Also noteworthy are the drinking horns found by Sutton Hoo and Taplow in the 7th century AD. In addition, a striking number of drinking horns were made from glass in the first half of the 1st millennium, which were traded from the Rhenish region to Scandinavia. Due to the often elaborate decorations with valuable materials, drinking horns are often seen as representative drinking vessels for special occasions, such as an official welcome drink, or for cultic religious acts. In 2003, a 7th century burial chamber was discovered in Prittlewell , which was also equipped with drinking horns and other eating utensils and may have been the burial place of King Sæberht .

Pictorial representations of drinking horns can be found on the Bayeux Tapestry and Gotlandic picture stones . In addition to the archaeological finds, these are of particular importance for research, as they are evidence of the times and not, as literary tradition was written centuries later.

The literary tradition is mainly about Old Norse sagas , in which drinking horns often play a role. The literarily most interesting drinking horn Grímr inn góði (Grim the good) can be found in Þorstein's Þáttr bæjarmagns , one of the prehistoric sagas. It is a magical drinking horn with a human head on top, which on the one hand confirms the power of its owner, but on the other hand can also predict the future. Such a representation of a drinking horn is unique in Norse literature, even if many other horns are mentioned. According to Bernhard Maier , " The 25th verse of Ragnar Lodbroks 'death song reports that the dead heroes in Valhalla drink beer' from the crooked woods of the skull" ". These "bjúgviðir hausa" mean nothing more than drinking horns.

A non-Nordic literary evidence for the use of drinking horns ( cornu urii ) is given by Gaius Iulius Caesar in De bello Gallico (Book 6, Chapter 28):

“Hoc se laboratories durant adulescentes atque hoc genere venationis exercent, et qui plurimos ex his interfecerunt, relatis in publicum cornibus, quae sint testimonio, magnam ferunt laudem. Sed adsuescere ad homines et mansuefieri ne parvuli quidem excepti possunt. Amplitudo cornuum et figura et species multum a nostrorum boum cornibus differt. Haec studiose conquisita ab labris argento circumcludunt atque in amplissimis epulis pro poculis utuntur. "

“That is why a lot of effort is put into catching them in pits and killing them: a laborious hunting business in which the young people practice and harden themselves; Great praise is therefore given to those who have killed the most and who show the animals' horns to the people as evidence of the deed. Incidentally, the aurochs never become tame and do not get used to people, even if they are caught very young; its horns are very different in width, shape, and appearance from the horns of our oxen; they are eagerly looking for them, surround the rim with silver and use them as a mug at gleaming feasts. "

However, the use of drinking horns was not limited to the European area. In the Scythian region in particular, many drinking horns made of gold were found, as well as depictions of drinking horns on gold plates. There are also more references to the use of horns as drinking and storage vessels from Africa and North America.

In the Gothic Middle Ages , drinking horns were the subject of elaborate artistic decoration, in that they were set in metal, primarily in gold-plated silver, and provided with a foot or even an architectural substructure. In addition to animal horns, hollowed-out elephant teeth, later rhinoceros and narwhal teeth, were used, which were either only polished or decorated with carvings. The renaissance made the drinking horn a pompous vessel of the highest luxury . Finally, the horns themselves were reproduced in glass and silver.

Nowadays they mostly serve as show pieces. Drinking horns are still used in the metal and medieval scene as well as by student associations and supporters of the Asatru .

Drinking horns on the Bayeux Tapestry (around 1070)

See also

further reading

- Detlev Ellmers: To the drinking utensils of the Viking Age. In: Offa . 21/22, 1964/65, pp. 21-43.

- Vera I. Evison: Germanic Glass Drinking Horns. In: Journal of Glass Studies. 17, 1975, pp. 74-87.

- Siegfried Gehrecke: The drinking horn in prehistoric times, with special consideration of the Roman Empire (= unprinted dissertation). Berlin 1950.

- J. Grüß: Two old Germanic drinking horns with remains of beer and meter. In: Prehistoric Journal . 22, 1931, pp. 180-191.

- Dirk Krauße: Drinking horn and Kline. For teaching the Greek oriental drinking customs to the early Celts. In: Germania . 71/1, 1993, pp. 188-197.

- Dirk Krauße: Hochdorf III. The drinking and dining service from the late Hallstatt prince grave of Eberdingen-Hochdorf (district of Ludwigsburg) (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. Volume 64). Stuttgart 1996.

- Christa Müller: The drinking horns of prehistoric times in Central Europe (= unprinted dissertation). Mainz 1955.

- Clara Redlich : On the drinking horn custom among the Germanic peoples of the older imperial era. In: Prehistoric Journal. 52, 1977, pp. 61-120.

- Jacqueline Simpson: Grímr the good, a magical drinking horn. In: Études Celtiques. 10/2, 1963, pp. 489-515.

- Carol Neumann de Vegvar: Drinking Horns in Ireland and Wales: Documentary Sources. In: Cormac Bourke (Ed.): From the Isles of the North. Early Medieval Art in Ireland and Britain. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Insular Art held in the Ulster Museum, Belfast, April 7-11, 1994. Belfast 1995, ISBN 0-337-11201-0 , pp. 81-87.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Johannes Hoops: Reallexikon der Germanic antiquity. Volume 13. Birds of Prey – Hardeknut. 2., completely reworked. and strong exp. Edition. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston, Mass. 1999, ISBN 3-11-016315-2 , p. 300. ( books.google.de )

- ↑ Matthias Schulz: ARCHEOLOGY King in the kitchen . In: Der Spiegel . No. 8 , 2004 ( online ).

- ↑ Þorsteins Þáttr bæjarmagns - 8. Frá drykkju ok viðræðu þeira Þorsteins. on snerpa.is

- ↑ Þorstein's þáttr bæjarmagns - Thorstein Mansion-Might. on notendur.hi.is (with English translation)

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. Gods - myths - worldview. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50280-6 , p. 140. ( books.google.de )

- ↑ Caesar - De bello Gallico 6.1–6.28: Fights in northern Gaul, 2nd Rhine crossing, excursus about Gaul and Germania. In: gottwein.de. Retrieved November 19, 2015 .

- ^ Scythian gold in the Greek style. - Section The Vessels. (PDF) at /hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de, accessed on November 19, 2015.