Ulrich Tengler

Ulrich Tengler , often documented as Tenngler , (* 1447 in Rottenacker , † 1511 in Höchstädt an der Donau ) was a German town clerk , lawyer , rentmaster and bailiff . He went down in the legal history of Germany as the author of the lay mirror .

Life

Ulrich Tengler was born in Rottenacker as the son of the local governor, Othmar Tengler. At the age of 7 Ulrich came to the grammar school in Ehingen to become a priest. At the age of 22 he entered the choir school in Blaubeuren.

Little is known about his youth; a rhymed obituary, in which it is reported, among other things, that he was a begging scholar on the road and a choir student in Blaubeuren, agrees so little with the researched life data that its authenticity has to be questioned. According to the investigations of Reinhard H. Seitz, Tengler was of noble origin, his later career and pictorial representations with coats of arms and in elegant clothes fit this.

According to Tengler's own statements, as a young man he was initially a court clerk in Heidenheim an der Brenz, which at that time belonged to Bavaria-Landshut, in order to take over the job of box clerk there before 1470, i.e. clerk for the lordly Kastner . The first major leap in his career then followed from 1479 as a senior council clerk (Pronotarius) in Nördlingen . Although the contract was extended for life in 1483 with an annual salary of 100 guilders, free accommodation and the privilege of “keeping two honest substitutes as clerk writers” , he gave up the position for unknown reasons at the end of the same year. But he felt obliged to “serve and support” the city out of gratitude that the mayor and council “out of a special affection for him and his children out of delight” .

From 1485 he was himself a Kastner in Heidenheim an der Brenz , from around 1495 a district judge and governor in Graisbach near Donauwörth. He then received the important bailiwick of Höchstädt on the Danube , which fell to the Palatinate Line in 1505 as part of the Duchy of Palatinate-Neuburg . In the princely services he gained a rich amount of practical experience and, according to his own statements, got "lessons and good teaching from highly trained, emptied and right-wing advice" . From his correspondence with his son Christoph, professor of canon law at Ingolstadt University, we know that Tengler was in contact with Ingolstadt scholars such as the poetry professor Jakob Locher (Philomusus).

Until now, science had assumed that Tengler wrote the Laienspiegel shortly before his death and that the (considerably expanded) New Laienspiegel was only printed after his death. Investigations on the occasion of the 500th year of creation of the legal book showed, however, that Ulrich Tengler lived until around 1521/22 and was also responsible for the expansion of the new edition.

Works

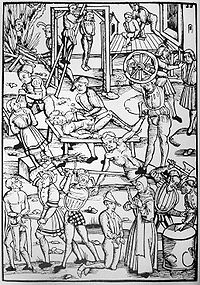

The Laienspiegel , also called Layenspiegel or Laijen Spiegel , is an important legal book of the early modern period. Tengler intended with him to convey Roman legal content in a popular way in German. Under the title “Laijen Spiegel. of lawful order in civil and embarrassing regiments. The law book was printed for the first time in 1509 with allegation [en] vn [d] evaluations out of written rights and sentences ” . The editor was the important publisher Johann Rynmann von Öhringen. The humanist, Strasbourg city clerk and assessor at the Reich Chamber of Commerce Sebastian Brant supported and praised Tengler's company.

The lay mirror saw an impressive 14 editions in the course of the 16th century and was in use all over Germany for 70 years. Together with the conceptually related Klagspiegel by Conrad Heyden , he shaped the so-called popular literature on Roman law in Germany. Complementing each other, the two works promoted the adoption of Roman law in German legal practice, probably more sustainably than any other writing, and served as a model for numerous other legal books. Only later did the learned literature slowly displace z. B. Zasius and his school this literary genre.

Tengler said he had to get involved in the persecution of the witches. He criticized the jurists' doubts about the reality of the witchcraft and blamed them for the extent and the increase. Time and again it is assumed that through his undeniable popularity in legal matters he contributed to this sorrowful and saddest aberration in the administration of justice. However, persecutions of witches in the area where the lay mirror is distributed can only be increasingly documented after 1580 - that is, after the main period of use of the lay mirror.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Museum Rottenacker, Village celebrities (2001)

- ↑ On this: Erich Kleinschmidt , Das "Epitaphium Ulrici Tenngler". An unknown obituary for the author of the "Laienspiegel" from 1511, in: Daphnis 6 (1977), 41-64.

- ↑ Andreas Deutsch: Tengler und der Laienspiegel , in: Andreas Deutsch (Hrsg.): Ulrich Tenglers Laienspiegel - A legal book between humanism and witchcraft , academy conferences vol. 11, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8253-5910-2 , p. 11–40, here p. 12 with further references

- ↑ Reinhard H. Seitz, On the biography of Ulrich Tenngler (approx. 1441–1521), Landvogt zu Höchstädt ad Donau and author of the Laienspiegel, in: Andreas Deutsch (Ed.): Ulrich Tenglers Laienspiegel - A legal book between humanism and witchcraft, academy conferences Vol. 11, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8253-5910-2 , pp. 55-98, 69 ff.

- ↑ Andreas Deutsch: Tengler und der Laienspiegel , in: Andreas Deutsch (Hrsg.): Ulrich Tenglers Laienspiegel - A legal book between humanism and witchcraft , academy conferences vol. 11, Heidelberg 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Roderich von Stintzing, History of the Popular Literature of Roman Canon Law in Germany, Leipzig 1867, p. 414.

- ↑ Andreas Deutsch, Laienspiegel, in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, URL: < http://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/artikel/artikel_45831 > (November 11, 2011)

- ↑ Reinhard H. Seitz: On the biography of Ulrich Tenngler (approx. 1441–1521), Landvogt zu Höchstädt ad Donau and author of the Laienspiegel , in: Andreas Deutsch (Hrsg.): Ulrich Tenglers Laienspiegel - A legal book between humanism and witchcraft , academy conferences Vol. 11, Heidelberg 2011, especially p. 78 ff.

- ^ Franz Fuchs, Jacob Locher Philomusus and Ulrich Tenngler, in: Andreas Deutsch: Tengler und der Laienspiegel , in: Andreas Deutsch (Ed.): Ulrich Tenglers Laienspiegel - A legal book between humanism and witchcraft , Academy Conferences Vol. 11, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8253-5910-2 , pp. 99-116, especially p. 108 ff.

literature

- Johann August Ritter von Eisenhart : Ulrich Tengler . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 37, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1894, pp. 568-670.

- Adalbert Erler: Article Tenngler , in: Handwortbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte 5 , Berlin 1998, pp. 145–146.

- Reinhard H. Seitz: On the biography of Ulrich Tenngler (approx. 1441–1521), Landvogt zu Höchstädt adDonau and author of the Laienspiegel, in: Andreas Deutsch (Ed.): Ulrich Tenglers Laienspiegel - A legal book between humanism and witchcraft , academy conferences vol. 11, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8253-5910-2 , pp. 55-98.

Web links

- Witch research in the HistoricumNet

- Andreas Deutsch, Article Laienspiegel, in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- Coat of arms of Christoph Tengler , with three hammering hammers as a symbol with a name reference and a unicorn as a symbol of royal jurisdiction; British Museum : Ros.367

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tengler, Ulrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tenngler, Ulrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German town clerk, lawyer, author of the lay mirror |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1447 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Heidenheim an der Brenz |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1511 |

| Place of death | Höchstädt on the Danube |