Volition (management)

In management science, the term volition describes the process of will formation (goal setting, planning) and will enforcement (organization, control) in relation to companies (self-regulating systems); In relation to executives , this term describes the willpower that is necessary in order to overcome conflicting motives, conflicting goals or feelings of displeasure. The competencies required for this result in greater efficiency in converting goals and motives into results, which can be measured using key figures .

Theory and meaning of volition

In everyday English (for example Oxford Dictionary), volition is understood to mean the use of will for decisions or simply the power of will. In the neurosciences , in psychology and in management (management cycle), the will relates to the control of the entire course of action - from the goal setting to the result (see Figure 1). This abstract model of the interplay of action and will is one of the most important keys to understanding human behavior. This ranges from the explanation of consumer behavior in marketing to the management of employees in sales (result orientation), entrepreneurial decisions in management to the treatment of behavioral disorders in psychology. As a result of more recent findings in brain research (see Haggard's article and the specialist literature cited there), the topic has attracted great interest in recent years. If you try to draw an interdisciplinary conclusion from the most important scientific contributions, you can draw the following picture (Figure 1):

At the beginning of a course of action there is the selection and definition of goals. This is followed by planning as a mental anticipation of the event, including the selection of suitable means to achieve the goal. This is followed by the implementation of the planned actions ( process or organization) in order to finally carry out a success check. In target-performance deviations corrective measures are necessary. In order for this process to run autonomously (or self-controlled), voluntary decisions are necessary in every phase . It is a result-oriented control influenced by the will, which leads to the realization of goals despite various disturbances from the environment and from the internal process. The greater the disruptions or target / actual deviations (problems), the more willpower is required. In order for this to be maintained, certain competencies ((1) to (5) in Figure 1) are required, which are described below. In summary, the term volition (in management) can be defined as the ability to translate motives and intentions into results (implementation skills ). This competence is especially important for (self-employed) entrepreneurs or managers because they have to shape the entire process on their own initiative and against numerous obstacles (self-control or self- management or self- management ). The opposite, namely extremely weak volitional skills, are expressed in the traditional diagnosis of mental disorders, among other things in weak will ( akrasia ), inhibition of will and will-blocking. Weakness of will can be recognized by a lack of drive, inconsistent pursuit of goals and a strong dependency on external influences. The special characteristics of the will inhibition are inability to make decisions, strong emotional ambivalences even with simple decisions, reluctance to set goals and a depressive inhibition of everyday activities. Blocking of will denotes the interruption of actions in the direction of the decision made. Neck and Houghton have compiled the most important research results of the last 20 years on this aspect of entrepreneurial self-control.

Emergence

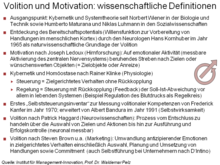

The subject was already dealt with by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in his work from 1819 under the title “The world as will and imagination”. Two other important contributions come from Friedrich Nietzsche (“The Will to Power”) from 1899 and from Narcissus Ach , who published his thoughts in a lecture entitled “On the Will” in 1910. His core idea is the "efficiency of will", which gives information about the success of human action, namely the "realization of what we want" in the face of resistance. Later, for various reasons, the subject of volition was neglected and received new impetus through the spread of cybernetic systems theory after the Second World War and, more recently, through advances in neuroscience . The contribution by Paul Karoly contains a more detailed overview of the development of the theory. The discovery of readiness potential by Hans Helmut Kornhuber (1928–2009) in 1965 as the physiological basis of volition should be emphasized . The topic thus moved away from philosophical discussions towards scientifically sound research. Frederick Kanfer (1925–2002) developed one of the first instruments for measuring volition in 1970. It was later refined further by Albert Bandura in 1991. Figure 2 on the right is intended to provide a comprehensive overview of the most important scientific terms in connection with the subject of volition.

Another important milestone in the development of the subject is certainly the work of Baumeister, Carver, Scheier and Vohs, which impressively illustrated the practical importance of volitional self-control in psychology . Baumeister, for example, thinks that most of the problems people face in our time can be traced back to inadequate self-regulation. This ranges from alcoholism, obesity, drug addiction and violence to the (mental) impoverishment of large sections of the population in so-called affluent societies. In management studies , Heike Bruch ( University of St. Gallen ) and Sumantra Ghoshal ( London Business School ) have brought the subject back to the attention of the specialist public. In a study they found that only about 10 percent of all managers complete their tasks with full energy and focus. The others are either hyperactive (but unsuccessful) or aloof and hesitant (and thus ineffective). The authors state that ambitious goals, high uncertainties and extreme resistance very quickly lead to the limits of motivation. Motivation is therefore not enough to meet the growing demands. What is needed is willpower. It is "... the power that lies behind energy and focus - (it) goes a decisive step beyond motivation." Managers with willpower overcome obstacles and setbacks and stay on course until they reach their goal. "Before that, Peter Drucker delivered in years 1954 an important building block in his book “The Practice of Management”. In it he called for “Management by Domination” to be replaced by “Management by Objects and Self-Control”. The English term “control” does not mean “control”, but rather steering or control (“direct oneself and one's work”). Peter Drucker said literally: "Self-control means stronger motivation: a desire to do the best ... Management by objectives and self-control asks for self-discipline. It forces the manager to make high demands on himself ... it assumes that people want to be responsible, want to contribute, want to achieve ... "

Practice and areas of application

One of the most important areas of application is the selection and development of management and management trainees with a view to future challenges. Another field can be found in marketing (consumer behavior). In management, the need for talented young people is becoming more and more urgent in view of the upcoming challenges in business and society. A study by management consultancy McKinsey even culminated in the catchphrase of the war for talented executives. The bottleneck is not with “any” managers, but with those who have volitional skills. This is namely the decisive key qualification of the future. In summary, one can describe self-control as the ability to convert motives, goals or wishes into actions so that these lead to concrete results (successes). So volition goes way beyond motivation . Often you have to (be able to) act against your own and other people's motives when it comes to achieving the necessary results. For people with strong volitional abilities, the vernacular has found a fitting metaphor: "Will moves mountains". Jack Welch quotes his mother, who gave him the following message on his path through life: "You just have to want it". The success of volitional competencies can be measured by how many intentions or goals a person has translated into results. Narcissus Ach already called this in 1910 the efficiency of will. The operationalization of the volitional skills can be done through behavioral descriptions of sub-competencies (labeled (1) to (5) in Figure 1).

- (1). Attention Control and Focus

- The person can concentrate on one thing for a long time and implement difficult actions even when there are strong adverse influences that impair motivation and attention.

- (2). Emotion and mood management

- The candidate is very good at putting himself in a positive mood and is able to skillfully deal with negative feelings. He acts on the principle that positive feelings help in the implementation of intentions. He can empathize with other people's thoughts and feelings.

- (3). Self-confidence and assertiveness

- The person has strong expectations of self-efficacy, is aware of and relies on their abilities. She always finds ways and means to get out of trouble quickly. Resistance and problems are seen as (feasible) challenges.

- (4). Forward planning and problem solving

- With a reactive attitude, the longer you delay a solution, the more pressing problems become. Therefore, a proactive, forward-looking attitude significantly increases the likelihood of success of actions (one is better prepared). In other words, this person takes care of uncomfortable and difficult problems immediately (instead of "sitting out" or putting off decisions).

- (5). Goal-related self-discipline

- This person recognizes what is necessary earlier than others and implements it consistently. She has a high degree of self-discipline and can effectively control sudden impulses, distractions or "temptations" (without internal struggles and conflict).

Tests (so-called self-control inventories) for diagnosing and "measuring" volitional competencies can be constructed from the behavioral descriptions. Examples for the general and clinical areas are those by Kuhl and Fuhrmann or by Mezo (Self-Control and Self-Management Scale). A self-control inventory (implementation skills) especially for specialists and managers was developed at the Steinbeis Institute for Management Innovation (see web links). The behavioral descriptions can also be used for so-called behavioral interviews in a management audit . As a rule, two reviewers get an impression of the candidate's skills in an interview. Then they create a "report" that can be used, for example, for career planning. You get even greater validity if you use the behavior descriptions in a 360-degree feedback , because the data allow a comparison of self-image and image of others. This gives you a reliable basis for planning your own personal and professional development (competencies).

The topic of volition is becoming increasingly important in marketing and sales. For example, one of the most important topics in marketing is how to explain purchasing decisions . Why does a customer buy product A (and not B)? What influenced his purchase decision the most? How will an advertising campaign affect purchasing behavior? Werner Kroeber-Riel in particular has made great strides in this area . In particular, he examined the importance of emotions in purchasing decisions (see Kroeber-Riel's model in Figure 3).

However, emotions are by no means sufficient to predict an action (purchase); but they are the basis of all human activity. In simple terms, one could say: without (measurable) emotion there is no action. If a goal orientation is added to the emotion, one speaks of a motivation . While an emotion is not yet targeted (it is just an inner excitement, which can be recognized, for example, by an increased heartbeat, clammy hands or a "tingling" feeling in the stomach), a motive has no concrete content. Examples of motives are status, power, independence, property, money, respect, or prestige. Motives play a major role in advertising, but they are insufficient to predict actions (purchase of a certain product). The connection (correlation) between motives and actions is simply too weak. Example: Someone wears a luxury watch for reasons of prestige and still buys at a discounter. That's why you go one step further in marketing and measure the attitude that follows the motif. The attitude consists of a motive and the knowledge (or the conviction) that a certain object is suitable to satisfy a certain motive. The relationship between attitude and action is still relatively weak, which makes advertising campaigns extremely expensive. This is exactly where a new area of research arises that has to do with volition, because between attitude and action comes the voluntary control of actions. So in the future you will not measure attitudes but volition if you want to make better predictions about consumer behavior .

supporting documents

- ↑ E. Heinen: Business management leadership. 2nd Edition. Wiesbaden 1984.

- ↑ H. Bruch, S. Ghoshal: Resolute leadership and action. Wiesbaden 2006, p. 30 f.

- ↑ a b W. Kroeber-Riel, P. Weinberg, A. Gröppel-Klein: Consumer behavior. 9th edition. Munich 2009.

- ^ SP Brown et al .: Effects of Goal-Directed Emotions on Salesperson Volitions, Behavior, and Performance. In: Journal of Marketing. Vol. 61, 1997, pp. 39-50.

- ↑ H. Bruch, S. Ghoshal: Resolute leadership and action. Wiesbaden 2006.

- ↑ RF Baumeister, JL Alquist: Self-Regulation as a Limited Resource. In: RF Baumeister et al. (Ed.): Psychology of Self-Regulation. New York 2009.

- ^ P. Haggard: Human Volition: Towards a Neuroscience of Will. In: Nature Reviews Neuroscience . 9, December 2008, pp. 934-946.

- ↑ W. Pelz: Focusing instead of getting bogged down: Willpower and implementation skills are a good omen for professional success. In: Personal, magazine for human resource management. No. 4/2010, p. 30 f.

- ↑ RS D'Intino et al .: Self-leadership: A process of entrepreneurial success. In: Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. Vol. 13, 2007.

- ↑ H.-U. Wittchen: Inability to exercise due to mental disorders. In: H. Heckhausen among others: Beyond the Rubicon, The will in the human sciences. Berlin et al. 1987.

- ^ CP Neck, JD Houghton: Two decades of self-leadership theory and research. In: Journal of Managerial Psychology. Vol. 21, 2006.

- ↑ N. Oh: About the act of will and temperament. Leipzig 1910.

- ↑ N. Oh: About the act of will and temperament. Leipzig 1910, p. 5.

- ↑ J. Beer et al .: Insights into Emotion Regulation from Neuropsychology. In: JJ Gross (Ed.): Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York 2007.

- ↑ KN Ochsner, JJ Gross: The Neural Architecture of Emotion regulation. In: JJ Gross (Ed.): Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York 2007.

- ^ P. Karoly: Mechanisms of Self-Regulation: A Systems View. In: Ann. Rev. Psychol. Vol. 44, 1993, pp. 23-52.

- ↑ HH Kornhuber, L. Deecke: Changes in brain potential in humans before and after voluntary movements. In: Pflüger's archive for the entire physiology. 284, 1965.

- ↑ J. Beer et al .: Insights into emotion regulation from neuropsychology. In: JJ Gross (Ed.): Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York 2007.

- ^ FH Kanfer: Self-regulation, Research, issues, and speculations. In: D. Neuringer, JL Michael, (Ed.): Behavior modification in clinical psychology. New York 1970.

- ^ A. Bandura: Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. In: Organizational behavior and human decision process. 50, 1991.

- ↑ RF Baumeister, KD Vohs, DM Tice: The Strength Model of Self-Control, Current Directions. In: Psychological Science. 16, 2007.

- ^ H. Bruch, S. Ghoshal: Beyond Motivation: The Power of Volition. In: Sloan Management Review. Spring 2003.

- ↑ H. Bruch, S. Ghoshal: Resolute leadership and action. Wiesbaden 2006, p. 31.

- ^ PF Drucker: The Practice of Management. New York 1986.

- ↑ PF Drucker: Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices. New York 1974, p. 439 f.

- ^ M. Maccoby: Leaders We Need. Harvard Business School Press, Boston 2007.

- ^ G. Hamel: The Future of Management. Harvard Business School Press, Boston 2007.

- ^ J. Welch: Winning. New York 2005.

- ^ J. Kuhl, A. Fuhrmann: Decomposing Self-Regulation and Self-Control: The Volitional Components Inventory. In: J. Heckhausen, CS Dweck: Motivation and Self-Regulation Across the Life Span. Cambridge (UK) 1998.

- ↑ PG Mezo: The Self-Control and Self-Management Scale: Development of an Adaptive Self-Regulatory Coping Skills Instrument. In: J. Psychol. Behav. Assess. 31, 2009, pp. 83-93.

- ↑ Specialists and managers .

- ^ PR Haunschild, M. Rhee: The Role of Volition in Organizational Learning: The Case of Automotive Product Recalls. In: Management Science. Vol. 50, No. 11, 2004, pp. 1545-1560.

- ^ SP Brown et al .: Effects of Goal-Directed Emotions on Salesperson Volitions, Behavior, and Performance. In: Journal of Marketing. Vol. 61, 1997, pp. 39-50.

- ^ P. Kotler, G. Armstrong: Principles of Marketing. 11th edition. Upper Saddler River / New Jersey 2006.

- ↑ R. Bagozzi, U. Dholakia: Goal Setting and Goal Striving in Consumer Behavior. In: Journal of Marketing. 63, 1999.

- ^ S. Reiss: Who Am I, The 16 Basic Desires That Motivate Our Actions and Define Our Personalities. New York 2000.

See also

literature

- N. Oh: About the will. Leipzig 1910.

- N. Oh: About the act of will and temperament. Leipzig 1910.

- A. Bandura: Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. In: Organizational behavior and human decision process. 50, 1991.

- R. Bagozzi, U. Dholakia: Goal Setting and Goal Striving in Consumer Behavior. In: Journal of Marketing. Vol. 63, 1999.

- RF Baumeister, JL Alquist: Self-Regulation as a Limited Resource. In: RF Baumeister et al. (Ed.): Psychology of Self-Regulation. New York 2009.

- RF Baumeister, KD Vohs, DM Tice: The Strength Model of Self-Control. In: Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16, 2007.

- J. Beer et al: Insights into Emotion Regulation from Neuropsychology. In: JJ Gross (Ed.): Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York 2007.

- SP Brown et al .: Effects of Goal-Directed Emotions on Salesperson Volitions, Behavior, and Performance. In: Journal of Marketing. Vol. 61, 1997, pp. 39-50.

- H. Bruch, S. Ghoshal: Leading and acting with determination. Wiesbaden 2006.

- H. Bruch, S. Ghoshal: Beyond Motivation: The Power of Volition. In: Sloan Management Review. Spring 2003.

- RS D'Intino et al: Self-leadership: A process of entrepreneurial success. In: Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. Vol. 13, 2007.

- PF Drucker: Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices. New York 1974.

- PF Drucker: The Practice of Management. New York 1986.

- JP Forgas et al: Psychology of Self-Regulation. New York 2009.

- E. Gutenberg: Basics of business administration. 18th edition. New York 1971.

- P. Haggard: Human Volition: Towards a Neuroscience of Will. In: Neuroscience. December 2008.

- PR Haunschild, M. Rhee: The Role of Volition in Organizational Learning: The Case of Automotive Product Recalls. In: Management Science. Vol. 50, No. 11, 2004, pp. 1545-1560.

- G. Hamel: The Future of Management. Harvard Business School Press, Boston 2007.

- E. Heinen: Business management theory. 2nd Edition. Wiesbaden 1984.

- FH Kanfer: Self-regulation, Research, issues, and speculations. In: D. Neuringer, JL Michael, (Ed.): Behavior modification in clinical psychology. New York 1970.

- P. Karoly: Mechanisms of Self-Regulation: A Systems View. In: Ann. Rev. Psychol. Vol. 44, 1993, pp. 23-52.

- J. Keller: An Integrative Theory of Motivation, Volition, and Performance. In: Tech., Inst., Cognition and Learning. 2008, pp. 79-104.

- R. Klinke, H.-C. Pape, S. Silbernagl (Ed.): Physiology. 5th edition. Stuttgart / New York 2005.

- HH Kornhuber, L. Deecke: Changes in brain potential in humans before and after voluntary movements. In: Pflüger's archive for the entire physiology. 284, 1965.

- P. Kotler, G. Armstrong: Principles of Marketing. 11th edition. Upper Saddler River / New Jersey 2006.

- J. Ledoux: The web of personality. Munich 2006.

- M. Maccoby: Leaders We Need. Harvard Business School Press, Boston 2007.

- PG Mezo: The Self-Control and Self-Management Scale: Development of an Adaptive Self-Regulatory Coping Skills Instrument. In: J. Psychol. Behav. Assess. 31, 2009, pp. 83-93.

- KN Ochsner, JJ Gross: The Neural Architecture of Emotion Regulation. In: JJ Gross (Ed.): Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York 2007.

- CP Neck, JD Houghton: Two decades of self-leadership theory and research. In: Journal of Managerial Psychology. Vol. 21, 2006.

- W. Pelz: Focusing instead of getting bogged down: Willpower and implementation skills are a good omen for professional success. In: Personal, magazine for human resource management. No. 4/2010.

- S. Reiss: Who Am I - The 16 Basic Desires That Motivate Our Actions and Define Our Personalities. New York 2000.

- Brian Tracy : No excuses! The power of self-discipline. Gabal, Offenbach 2011, ISBN 978-3-86936-235-9 .

- J. Welch: Winning. New York 2005.