Circus parties

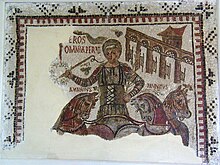

The circus parties (Latin partes or factiones , Greek demoi or moirai ; rarely also: stadium parties ) were the racing stables in the Roman Empire and the later Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire , which increasingly had political importance. From late antiquity to the 9th century, a considerable part of the mass of the urban population of Constantinople / Byzantium (now Istanbul ), which was mostly assigned to the lower class, was organized in them. They gained political influence because they could mobilize or instrumentalize the people politically and ecclesiastically by participating in the games, theater and chariot races in the hippodrome . For a time, the parties expanded to other cities in the empire (besides Rome and Constantinople) that had car racing tracks. Their influence on the central government was sometimes significant. Although they were still active in the west of the Mediterranean in the 5th and 6th centuries , as evidenced by statements made by Cassiodorus ( Variae 3,51,11), they were still a phenomenon that was mainly restricted to the East.

history

The circus parties emerged as early as the Roman Empire , with four equal racing stables with their supporters initially: prasina 'the green', veneta 'the blue', russata 'the red' and albata 'the white'. At least in later times the colors were traced back to the four elements fire (red), water (blue), air (white) and earth (green). In late antiquity (284 to 641 AD), the two major parties, the Blue and Green, had "branches" in all of the major cities that had a circus or hippodrome. Since, after the partial collapse of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 7th century, chariot races were held almost exclusively in Constantinople, the influence of the circus parties was limited to the capital from this time on.

The emperors or, beyond the capital, their deputies had to regularly show themselves to the people ( populus or demos ) in the circus, to whom the circus parties gave a voice: the acclamations they orchestrated were the most important medium of communication between the late Roman emperor and his subjects . Since the late antique state system in fact provided for an autocratic rule by the emperor, real participation of the population in politics was hardly planned; at the same time, however, the consent of the people was regarded as an indispensable prerequisite for legitimate rule. If it was missing, uprisings and usurpations threatened. In fact, the partes formed , at least temporarily, an essential factor in domestic politics that no emperor could ignore without consequences.

The red and white parties lost their importance early on. As early as the second half of the 2nd century, Emperor Mark Aurel only mentions the "Greens" and the "Blues" when he speaks of having learned not to favor any party ( Meditationes 1.5). In late antiquity there was in fact only the party of the “blues”, the venetoi (mostly with the “whites” as “ junior partners ”), and that of the “greens”, the prasinoi (with the “reds”), the im They were essentially identical to the urban districts (Demen), which also served as a citizen militia, and were led by a demarch. A close relationship between individual emperors and certain partes has already been documented for the early and high imperial period ( principality ); According to Cassius Dio, Emperor Caracalla had the famous charioteer Euprepes executed in 211 because he drove for a party other than that preferred by the ruler (Cass. Dio 78,1,2). But in late antiquity this phenomenon grew in importance.

The political influence of the demarches as leaders of the circus parties ended during the Macedonian dynasty (the descendants of Emperor Basil I , † 886) through a reorganization of the hierarchy of officials.

Relations between the emperor and the parties

Numerous examples of direct influence on the emperors or the connection between parties and the imperial family are known, especially since the 5th century:

- An emperor known to have a special relationship with the partes was Theodosius II , under whom the earliest recorded riots of the circus parties in Constantinople took place in 445.

- Emperor Anastasius , who was unusually a supporter of the Reds, was repeatedly confronted with serious circus unrest around 500, which his contemporary Marcellinus Comes (ad ann. 493) even referred to as bella civilia ; the Staurotheis uprising, with significant participation by the Greens and Blues, almost led to the fall of the emperor in 512.

- Empress Theodora , the wife of Justinian (527-565), came from a family working for the Green Party. Like her mother, she herself was a dancer, actress and prostitute in her youth. When the mother remarried after the death of her father, the stepfather was not accepted by the Greens, but was accepted by the Blues.

- During Justinian's reign, tensions between the emperor and the circus parties escalated in the Nika uprising in 532 , after Justinian had ringleaders from both parties executed. When two of them were about to be hanged again, despite the gallows collapsing under their weight, the parties demanded their pardon. After Justinian had instead demonstratively refused to communicate with the people gathered in the hippodrome, riots broke out. The supporters of the Green and Blue united against Justinian, formed under the battle cry Nika! Nika! (Siege! Siege!) And even proclaimed Hypatius as a counter-emperor; but Justinian, allegedly under the influence of Theodoras, managed to bloody suppress the uprising with the help of his generals Narses and Belisarius .

- Emperor Maurikios (582–602) also turned both parties against him (with the Greens as the driving force and the Blue as benevolent observers), which led to his overthrow.

- The longstanding one-sided partisanship of his successor, Emperor Phokas (602–610), for the Blues against the Greens initially favored by him plunged the empire into civil war.

- The first term of office of Emperor Justinian II (685-695, 705-711) ended due to an uprising led by the blues.

- Emperor Michael III. (842–867) was a Blue Party favorite in his youth while his mother was in power.

Political orientation

A primarily political orientation of the circus parties is mostly disputed today. A role limited to the organization of the racing stables, circus events and other forms of entertainment such as theater is seen, and the ruler's partisanship for a color is interpreted more as an expression of “closeness to the people” (e.g. Alan Cameron, Circus Factions , 1976).

For a long time, the blue was considered traditional Chalcedonite- Orthodox, the green as monophysite . However, there are weighty dissenting voices (Cameron) who consider such an assignment to be wrong; in more recent research these objections are mostly followed. This position has recently been put into perspective again (e.g. by Michael Whitby and Mischa Meier), and a really satisfactory explanation of the phenomenon has not yet been found.

literature

- Peter Bell: How the Circus and Theater Factions could help prevent Civil War . In: Henning Börm , Marco Mattheis, Johannes Wienand (Eds.): Civil War in Ancient Greece and Rome . Stuttgart 2016, pp. 389-413. (Bell takes the position that the circus parties prevented the escalation of violence more often than promoted it.)

- Alan Cameron : Circus factions. Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium . Oxford 1976. (Standard work on the subject. Cameron advocates a fundamentally apolitical character of circus parties.)

- Mischa Meier : Anastasios I. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 148-173.

- Michael Whitby: The violence of the circus factions . In: Keith Hopwood (Ed.): Organized Crime in Antiquity . Swansea 1999, pp. 229-253. (Good overview of the recent research)

- Hans-Ulrich Wiemer : Acclamations in the late Roman Empire. On the typology and function of a communication ritual . In: AKG 86, 2004, pp. 27-73.