Graveyard poets: Difference between revisions

m Replace magic links with templates per local RfC and MediaWiki RfC |

Reverted 1 edit by Merkurïïï (talk): Link to blog post that looks like it's just a paraphrase of the Wikipedia article |

||

| (39 intermediate revisions by 24 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|Graveyard School|the novellas by Tom B. Stone|Graveyard School (novella series)}} |

{{redirect|Graveyard School|the novellas by Tom B. Stone|Graveyard School (novella series)}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The ''' |

The "'''Graveyard Poets'''", also termed "'''Churchyard Poets'''",<ref>{{cite web|title=Graveyard Poets|url=http://people.duke.edu/~tmw15/graveyard%20poets.html|work=Vade Mecum: A GRE for Literature Study Tool|publisher=Duke|access-date=8 December 2012|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131002191458/http://people.duke.edu/~tmw15/graveyard%20poets.html|archive-date=2 October 2013}}</ref> were a number of pre-Romantic poets of the 18th century characterised by their gloomy meditations on [[death|mortality]], "skulls and coffins, epitaphs and worms"<ref>Blair: ''The Grave'' 23</ref> elicited by the presence of the graveyard. Moving beyond the [[elegy]] lamenting a single death, their purpose was rarely sensationalist. As the century progressed, "graveyard" poetry increasingly expressed a feeling for the "[[Sublime (philosophy)|sublime]]" and uncanny, and an [[Antiquarianism|antiquarian]] interest in ancient English poetic forms and folk poetry. The "graveyard poets" are often recognized as precursors of the [[Gothic fiction|Gothic literary genre]], as well as the [[Romanticism|Romantic]] movement. |

||

==Overview== |

==Overview== |

||

The Graveyard School is an indefinite literary grouping that binds together a wide variety of authors; what makes a poem a "graveyard" poem remains open to critical dispute. At its narrowest the term "Graveyard School" refers to four poems: Thomas Gray's [[Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard]], Thomas Parnell's "Night-Piece |

The Graveyard School is an indefinite literary grouping that binds together a wide variety of authors; what makes a poem a "graveyard" poem remains open to critical dispute. At its narrowest, the term "Graveyard School" refers to four poems: [[Thomas Gray|Thomas Gray's]] "[[Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard]]", Thomas Parnell's "Night-Piece on Death", Robert Blair's ''[[The Grave (poem)|The Grave]]'' and [[Edward Young|Edward Young's]] ''[[Night-Thoughts]]''. At its broadest, it can describe a host of poetry and prose works popular in the early and mid-eighteenth century. The term itself was not used as a brand for the poets and their poetry until William Macneile Dixon did so in 1898.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title = Graveyard Poetry: Religion, Aesthetics, and the Mid-Eighteenth-Century Poetic Condition|last = Parisot|first = Eric|publisher = Ashgate|year = 2013|isbn = 1409434737}}</ref> |

||

Some literary critics have emphasized Milton's minor poetry as the main influence of the meditative verse written by the Graveyard Poets. W. L. Phelps, for example, said |

Some literary critics have emphasized [[John Milton|Milton]]'s minor poetry as the main influence of the meditative verse written by the Graveyard Poets. W. L. Phelps, for example, said: "It was not so much in form as in thought that Milton affected the Romantic movement; and although ''[[Paradise Lost]]'' was always reverentially considered his greatest work, it was not at this time nearly so effective as his minor poetry; and in the latter it was ''[[Il Penseroso]]'' — the love of meditative comfortable melancholy — that penetrated most deeply into the Romantic soul".<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|title = The graveyard school of poets|last = Huff|first = James|publisher = Thesis (M.A.) University of Illinois|year = 1912|location = Illinois|pages = 65}}</ref> However, other critics like Raymond D. Havens, Harko de Maar and [[Eric Partridge]] have challenged the direct influence of Milton's poem, claiming rather that graveyard poetry came from a culmination of literary precedents.<ref name=":0" /> As a result of the religious revival, the early eighteenth century was a time of both spiritual unrest and regeneration; therefore, meditation and melancholy, death and life, ghosts and graveyards, were attractive subjects to poets at that time. These subjects were, however, interesting to earlier poets as well. The Graveyard School's melancholy was not new to English poetry, but rather a continuation of that of previous centuries; there is even an elegiac quality to the poems almost reminiscent of Anglo-Saxon literature.<ref name=":1" /> The characteristics and style of Graveyard poetry is not unique to them, and the same themes and tone are found in [[ballad]]s and [[ode]]s. |

||

Many of the Graveyard School poets were, like Thomas Parnell, Christian clergymen, and as such they often wrote didactic poetry, combining aesthetics with religious and moral instruction.<ref name=":0" /> They were also inclined toward contemplating subjects related to life after death,<ref name=":1" /> which is reflected in how their writings focus on human mortality and |

Many of the Graveyard School poets were, like [[Thomas Parnell]], Christian clergymen, and as such they often wrote didactic poetry, combining aesthetics with religious and moral instruction.<ref name=":0" /> They were also inclined toward contemplating subjects related to life after death,<ref name=":1" /> which is reflected in how their writings focus on human mortality and man's relation to the divine. The religious culture of the mid-eighteenth century included an emphasis on private devotion, as well as the end of printed funeral sermons. Each of these conditions demanded a new kind of text with which people could meditate on life and death in a personal setting. The Graveyard School met that need, and the poems were thus quite popular, especially with the middle class.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|jstor=2765949|volume=35| doi=10.1086/215156|title = Review of "The Funeral Elegy, and the Rise of English Romanticism" by John W. Draper|last = Clark|first = Carroll|date = Jan 1930|journal = American Journal of Sociology }}</ref> For instance [[Elizabeth Singer Rowe|Elizabeth Singer Rowe's]] ''Friendship in Death: In Twenty Letters from the Dead to the Living'', published in 1728, had 27 editions printed by 1760. This popularity, as Parisot says, "confirms the fashionable mid-century taste for mournful piety."<ref name=":0" /> Thomas Gray, who found inspiration in a churchyard, claimed to have a naturally melancholy spirit, writing in a letter that "low spirits are my true and faithful companions; they get up with me, go to bed with me; make journeys and returns as I do; nay, and pay visits, and will even affect to be jocose, and force a feeble laugh with me; but most commonly we sit alone together, and are the prettiest insipid company in the world".<ref name=":1" /> |

||

The works of the Graveyard School continued to be popular into the early 19th century and were instrumental in the development of the [[Gothic fiction|Gothic novel]], contributing to the dark, mysterious mood and story lines that characterize the |

The works of the Graveyard School continued to be popular into the early 19th century and were instrumental in the development of the [[Gothic fiction|Gothic novel]], contributing to the dark, mysterious mood and story lines that characterize the genre — Graveyard School writers focused their writings on the lives of ordinary and unidentified characters. They are also considered pre-Romanticists, ushering in the [[Romantic poetry|Romantic]] literary movement<ref name=":2" /> by their reflection on emotional states. This emotional reflection is seen in Coleridge's "[[Dejection: An Ode]]" and Keats' "[[Ode on Melancholy]]". The early works of Southey, Byron and Shelley also show the influence of the Graveyard School. |

||

== |

==Partial list of Graveyard Poets== |

||

{{Unreferenced section|date=June 2022}} |

|||

* [[Thomas Parnell]] |

* [[Thomas Parnell]] |

||

* [[John Keats]] |

|||

* [[Thomas Warton]] |

* [[Thomas Warton]] |

||

* [[Thomas Percy ( |

* [[Thomas Percy (bishop of Dromore)|Thomas Percy]] |

||

* [[Thomas Gray]] |

* [[Thomas Gray]] |

||

* [[Oliver Goldsmith]] |

* [[Oliver Goldsmith]] |

||

* [[William Cowper]] |

* [[William Cowper]] |

||

* [[Christopher Smart]] |

* [[Christopher Smart]] |

||

* [[James Macpherson |

* [[James Macpherson]] |

||

* [[Robert Blair (poet)|Robert Blair]] |

* [[Robert Blair (poet)|Robert Blair]] |

||

* [[William Collins (poet)|William Collins]] |

* [[William Collins (poet)|William Collins]] |

||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

* [[Joseph Warton]] |

* [[Joseph Warton]] |

||

* [[Henry Kirke White]] |

* [[Henry Kirke White]] |

||

* [[Edward Young]] |

* [[Edward Young]] |

||

* [[David Mallet (writer)|David Mallet]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[William Mason (poet)|William Mason]] |

|||

* [[James Beattie (poet)|James Beattie]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

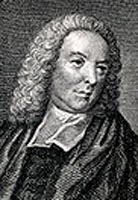

[[File:Edward Young Poet.jpeg|thumbnail|Edward Young]] |

[[File:Edward Young Poet.jpeg|thumbnail|Edward Young]] |

||

==Criticism== |

==Criticism== |

||

Many critics of Graveyard poetry had very little positive feedback for the poets and their work. |

Many critics of Graveyard poetry had very little positive feedback for the poets and their work. Critic Amy Louise Reed called Graveyard poetry a disease,<ref>{{cite journal|last=Reed|first=Amy Louise|title=The Revolt Against Melancholy|journal=The Background of Gray's Elegy|year=1924|pages=80–139}}</ref> while other critics called many poems unoriginal, and said that the poets were better than their poetry.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Johnson|first=Samuel|title=Gray|journal=In Lives of the English Poets|year=1905|volume=3|pages=421–25}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Johnson|first=Samuel|title=Parnell|journal=In Lives of the English Poets|year=1905|volume=2|pages=49–56}}</ref> Although the majority of criticism about Graveyard poetry is negative, other critics thought differently, especially about poet [[Edward Young]]. Critic Isabell St. John Bliss also celebrates [[Edward Young]]’s ability to write his poetry in the style of the Graveyard School and at the same time include [[Christianity|Christian]] themes,<ref>{{cite journal|last=St. John Bliss|first=Isabel|title=Young's Night Thoughts in Relation to Contemporary Christian Apologetics|journal=PMLA|date=March 1934|pages=49}}</ref> and Cecil V. Wicker called Young a forerunner in the Romantic movement and described his work as original.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Wicker|first=Cecil V.|title=Young as a Romanticist|journal=Edward Young and the Fear of Death: A Study of Romantic Melancholy|year=1952|pages=11–22; 23–27}}</ref> Eric Parisot claimed that fear is created as a spur to faith and that in Graveyard poetry, "...it is only when we restore religion — to examine the various ways graveyard poetry exploited fear and melancholy — that we can fully grasp its enduring contribution to the Gothic..."<ref>{{Cite book|last=Parisot|first=Eric|chapter=Gothic and Graveyard Poetry: Imagining the Dead (of Night)|title=The Edinburgh Companion to Gothic and the Arts |editor=David Punter |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |location=Edinburgh |year=2019 |pages=245–258|jstor=10.3366/j.ctvrs9173.21}}</ref> |

||

== |

==Poem samples== |

||

[[File:Young-Night-Thoughts-Blake.jpg|thumb|An illustration for Young's [[Night |

[[File:Young-Night-Thoughts-Blake.jpg|thumb|An illustration for Young's ''[[Night-Thoughts]]'' by [[William Blake]].]] |

||

The earliest poem attributed to the Graveyard |

The earliest poem attributed to the Graveyard School was Thomas Parnell's ''A Night-Piece on Death'' ([[1721 in poetry|1721]]),<ref>{{cite book |last=Kendrick |first=Walter |author-link= |date=1991 |title=The Thrill of Fear: 250 Years of Scary Entertainment |url= |location=New York |publisher=Grove Weidenfeld |page=10-11 |isbn=0-8021-1162-9}}</ref> in which King Death himself gives an address from his kingdom of bones: |

||

:"When men my scythe and darts supply |

:"When men my scythe and darts supply |

||

:How great a King of Fears am I!" (61–62) |

:How great a King of Fears am I!" (61–62) |

||

Characteristic later poems include |

Characteristic later poems include Edward Young's ''[[Night-Thoughts]]'' ([[1742 in poetry|1742]]), in which a lonely traveller in a graveyard reflects lugubriously on: |

||

:The vale funereal, the sad cypress gloom; |

:The vale funereal, the sad cypress gloom; |

||

| Line 53: | Line 57: | ||

:And the great bell has tolled, unrung and untouched. (51–53) |

:And the great bell has tolled, unrung and untouched. (51–53) |

||

However a more contemplative |

However, a more contemplative mood is achieved in the celebrated opening verse of Gray's ''[[Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard]]'' ([[1751 in poetry|1751]]<ref name=cocel>"Published on 15 February 1751 in a quarto pamphlet, according to Cox, Michael, editor, ''The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2004, {{ISBN|0-19-860634-6}}</ref>): |

||

:The curfew tolls the knell of parting day. |

:The curfew tolls the knell of parting day. |

||

| Line 60: | Line 64: | ||

:And leaves the world to darkness and to me. (1–4) |

:And leaves the world to darkness and to me. (1–4) |

||

==See also== |

|||

The Graveyard Poets were notable and influential figures, who created a stir in the public mind, and marked a shift in mood and form in English poetry, in the second half of the 18th century, which eventually led to [[Romanticism]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Schools of poetry}} |

{{Schools of poetry}} |

||

| Line 72: | Line 76: | ||

[[Category:Poetry movements]]<!--closest category for genre or type--> |

[[Category:Poetry movements]]<!--closest category for genre or type--> |

||

[[Category:18th century in England]] |

[[Category:18th century in England]] |

||

[[Category:English poets]] |

[[Category:English male poets]] |

||

[[Category:British poetry]] |

[[Category:British poetry]] |

||

[[Category:18th-century British literature]] |

[[Category:18th-century British literature]] |

||

Latest revision as of 00:23, 15 November 2023

The "Graveyard Poets", also termed "Churchyard Poets",[1] were a number of pre-Romantic poets of the 18th century characterised by their gloomy meditations on mortality, "skulls and coffins, epitaphs and worms"[2] elicited by the presence of the graveyard. Moving beyond the elegy lamenting a single death, their purpose was rarely sensationalist. As the century progressed, "graveyard" poetry increasingly expressed a feeling for the "sublime" and uncanny, and an antiquarian interest in ancient English poetic forms and folk poetry. The "graveyard poets" are often recognized as precursors of the Gothic literary genre, as well as the Romantic movement.

Overview[edit]

The Graveyard School is an indefinite literary grouping that binds together a wide variety of authors; what makes a poem a "graveyard" poem remains open to critical dispute. At its narrowest, the term "Graveyard School" refers to four poems: Thomas Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard", Thomas Parnell's "Night-Piece on Death", Robert Blair's The Grave and Edward Young's Night-Thoughts. At its broadest, it can describe a host of poetry and prose works popular in the early and mid-eighteenth century. The term itself was not used as a brand for the poets and their poetry until William Macneile Dixon did so in 1898.[3]

Some literary critics have emphasized Milton's minor poetry as the main influence of the meditative verse written by the Graveyard Poets. W. L. Phelps, for example, said: "It was not so much in form as in thought that Milton affected the Romantic movement; and although Paradise Lost was always reverentially considered his greatest work, it was not at this time nearly so effective as his minor poetry; and in the latter it was Il Penseroso — the love of meditative comfortable melancholy — that penetrated most deeply into the Romantic soul".[4] However, other critics like Raymond D. Havens, Harko de Maar and Eric Partridge have challenged the direct influence of Milton's poem, claiming rather that graveyard poetry came from a culmination of literary precedents.[3] As a result of the religious revival, the early eighteenth century was a time of both spiritual unrest and regeneration; therefore, meditation and melancholy, death and life, ghosts and graveyards, were attractive subjects to poets at that time. These subjects were, however, interesting to earlier poets as well. The Graveyard School's melancholy was not new to English poetry, but rather a continuation of that of previous centuries; there is even an elegiac quality to the poems almost reminiscent of Anglo-Saxon literature.[4] The characteristics and style of Graveyard poetry is not unique to them, and the same themes and tone are found in ballads and odes.

Many of the Graveyard School poets were, like Thomas Parnell, Christian clergymen, and as such they often wrote didactic poetry, combining aesthetics with religious and moral instruction.[3] They were also inclined toward contemplating subjects related to life after death,[4] which is reflected in how their writings focus on human mortality and man's relation to the divine. The religious culture of the mid-eighteenth century included an emphasis on private devotion, as well as the end of printed funeral sermons. Each of these conditions demanded a new kind of text with which people could meditate on life and death in a personal setting. The Graveyard School met that need, and the poems were thus quite popular, especially with the middle class.[5] For instance Elizabeth Singer Rowe's Friendship in Death: In Twenty Letters from the Dead to the Living, published in 1728, had 27 editions printed by 1760. This popularity, as Parisot says, "confirms the fashionable mid-century taste for mournful piety."[3] Thomas Gray, who found inspiration in a churchyard, claimed to have a naturally melancholy spirit, writing in a letter that "low spirits are my true and faithful companions; they get up with me, go to bed with me; make journeys and returns as I do; nay, and pay visits, and will even affect to be jocose, and force a feeble laugh with me; but most commonly we sit alone together, and are the prettiest insipid company in the world".[4]

The works of the Graveyard School continued to be popular into the early 19th century and were instrumental in the development of the Gothic novel, contributing to the dark, mysterious mood and story lines that characterize the genre — Graveyard School writers focused their writings on the lives of ordinary and unidentified characters. They are also considered pre-Romanticists, ushering in the Romantic literary movement[5] by their reflection on emotional states. This emotional reflection is seen in Coleridge's "Dejection: An Ode" and Keats' "Ode on Melancholy". The early works of Southey, Byron and Shelley also show the influence of the Graveyard School.

Partial list of Graveyard Poets[edit]

- Thomas Parnell

- John Keats

- Thomas Warton

- Thomas Percy

- Thomas Gray

- Oliver Goldsmith

- William Cowper

- Christopher Smart

- James Macpherson

- Robert Blair

- William Collins

- Thomas Chatterton

- Mark Akenside

- Joseph Warton

- Henry Kirke White

- Edward Young

- David Mallet

- William Mason

- James Beattie

- James Thomson is also sometimes included as a Graveyard Poet.

Criticism[edit]

Many critics of Graveyard poetry had very little positive feedback for the poets and their work. Critic Amy Louise Reed called Graveyard poetry a disease,[6] while other critics called many poems unoriginal, and said that the poets were better than their poetry.[7][8] Although the majority of criticism about Graveyard poetry is negative, other critics thought differently, especially about poet Edward Young. Critic Isabell St. John Bliss also celebrates Edward Young’s ability to write his poetry in the style of the Graveyard School and at the same time include Christian themes,[9] and Cecil V. Wicker called Young a forerunner in the Romantic movement and described his work as original.[10] Eric Parisot claimed that fear is created as a spur to faith and that in Graveyard poetry, "...it is only when we restore religion — to examine the various ways graveyard poetry exploited fear and melancholy — that we can fully grasp its enduring contribution to the Gothic..."[11]

Poem samples[edit]

The earliest poem attributed to the Graveyard School was Thomas Parnell's A Night-Piece on Death (1721),[12] in which King Death himself gives an address from his kingdom of bones:

- "When men my scythe and darts supply

- How great a King of Fears am I!" (61–62)

Characteristic later poems include Edward Young's Night-Thoughts (1742), in which a lonely traveller in a graveyard reflects lugubriously on:

- The vale funereal, the sad cypress gloom;

- The land of apparitions, empty shades! (117–18)

Blair's The Grave (1743) proves to be no more cheerful as it relates with grim relish how:

- Wild shrieks have issued from the hollow tombs;

- Dead men have come again, and walked about;

- And the great bell has tolled, unrung and untouched. (51–53)

However, a more contemplative mood is achieved in the celebrated opening verse of Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751[13]):

- The curfew tolls the knell of parting day.

- The lowing herd winds slowly o'er the lea,

- The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

- And leaves the world to darkness and to me. (1–4)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Graveyard Poets". Vade Mecum: A GRE for Literature Study Tool. Duke. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Blair: The Grave 23

- ^ a b c d Parisot, Eric (2013). Graveyard Poetry: Religion, Aesthetics, and the Mid-Eighteenth-Century Poetic Condition. Ashgate. ISBN 1409434737.

- ^ a b c d Huff, James (1912). The graveyard school of poets. Illinois: Thesis (M.A.) University of Illinois. p. 65.

- ^ a b Clark, Carroll (Jan 1930). "Review of "The Funeral Elegy, and the Rise of English Romanticism" by John W. Draper". American Journal of Sociology. 35. doi:10.1086/215156. JSTOR 2765949.

- ^ Reed, Amy Louise (1924). "The Revolt Against Melancholy". The Background of Gray's Elegy: 80–139.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel (1905). "Gray". In Lives of the English Poets. 3: 421–25.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel (1905). "Parnell". In Lives of the English Poets. 2: 49–56.

- ^ St. John Bliss, Isabel (March 1934). "Young's Night Thoughts in Relation to Contemporary Christian Apologetics". PMLA: 49.

- ^ Wicker, Cecil V. (1952). "Young as a Romanticist". Edward Young and the Fear of Death: A Study of Romantic Melancholy: 11–22, 23–27.

- ^ Parisot, Eric (2019). "Gothic and Graveyard Poetry: Imagining the Dead (of Night)". In David Punter (ed.). The Edinburgh Companion to Gothic and the Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 245–258. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctvrs9173.21.

- ^ Kendrick, Walter (1991). The Thrill of Fear: 250 Years of Scary Entertainment. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. p. 10-11. ISBN 0-8021-1162-9.

- ^ "Published on 15 February 1751 in a quarto pamphlet, according to Cox, Michael, editor, The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-860634-6

- Noyes, Russell (Ed.) (1956). English Romantic Poetry and Prose. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-501007-8