Gabriello Chiabrera: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Removing from Category:Italian poets Diffusing per WP:DIFFUSE and/or WP:ALLINCLUDED using Cat-a-lot |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by 17 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Italian poet and playwright, 1552–1638}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Infobox writer |

|||

| ⚫ | '''Gabriello Chiabrera''' ({{IPA-it|ɡabriˈɛllo kjaˈbrɛːra}}; 18 June 1552{{snd}}14 October 1638) was an |

||

|name = Gabriello Chiabrera |

|||

|image = Ottavio Leoni, Gabriello Chiabrera, 1625, NGA 159736.jpg |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1552|06|18}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[Savona]], [[Republic of Genoa]] |

|||

|death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1638|10|14|1552|06|18}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Savona]], [[Republic of Genoa]] |

|||

|resting_place = |

|||

|occupation = Poet |

|||

|nationality = [[Italy|Italian]] |

|||

|movement = [[Baroque]] |

|||

|period = [[Late Middle Ages]] |

|||

|notableworks = ''Canzonette''<br />''[[Il rapimento di Cefalo]]''<br/>''[[Orfeo dolente]]'' |

|||

|language = [[Italian language|Italian]] |

|||

|spouse = Lelia Pavese |

|||

|children = |

|||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ | '''Gabriello Chiabrera''' ({{IPA-it|ɡabriˈɛllo kjaˈbrɛːra}}; 18 June 1552{{snd}}14 October 1638) was an Italian [[poet]], sometimes called the Italian [[Pindar]].<ref name="EB1911">{{EB1911|inline=1|wstitle=Chiabrera, Gabriello|volume=6|page=117}} Endnote: The best editions of Chiabrera are those of Rome (1718, 3 vols. 8vo); of Venice (1731, 4 vols. 8vo); of Leghorn (1781, 5 vols., 12mo); and of Milan (1807, 3 vols. 8vo). These only contain his lyric work; all the rest he wrote has been long forgotten.</ref> His "new metres and a Hellenic style enlarged the range of lyric forms available to later Italian poets."<ref>Jarndyce Catalogue No. CCLI, London, Autumn 2021, Item 134.</ref> |

||

==Biography== |

|||

Chiabrera was of [[Patrician (post-Roman Europe)|patrician]] descent |

Chiabrera was of [[Patrician (post-Roman Europe)|patrician]] descent and born at [[Savona]], a little town in the domain of the [[Republic of Genoa|Genoese]] republic, 28 years after the birth of [[Pierre de Ronsard]], with whom he has more in common than with the great Greek whose echo he sought to make himself. As he states in a pleasant fragment of autobiography prefixed to his works, where like [[Julius Caesar]] he speaks of himself in the third person, he was a posthumous child; he went to [[Rome]] at the age of nine, under the care of his uncle Giovanni. There he read with a private tutor, suffered severely from two fevers in succession, and was sent at last, for the sake of society, to the [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit]] College, where he remained till his 20th year, studying philosophy, as he says, "rather for occupation than for learning's sake".<ref name="EB1911"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Losing his uncle about this time, Chiabrera returned to Savona, "again to see his own and be seen by them." |

||

| ⚫ | Losing his uncle about this time, Chiabrera returned to Savona, "again to see his own and be seen by them." A little while later he returned to Rome and entered the household of a [[cardinal (Catholicism)|cardinal]], where he remained for several years, frequenting the society of [[Paulus Manutius]] and of [[Sperone Speroni]], the dramatist and critic of [[Torquato Tasso|Tasso]], and attending the lectures and hearing the conversation of [[Muretus]]. His revenge of an insult offered him obliged him to betake himself once more to Savona, where, to amuse himself, he read poetry, and particularly [[Greek language|Greek]].<ref name="EB1911"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Poets of his choice were Pindar and [[Anacreon (poet)|Anacreon]]. These he studied until it became his ambition to reproduce in his own tongue their rhythms and structures and to enrich his country with a new form of verse, and "like his country-man, [[Christopher Columbus|Columbus]], to find a new world or drown." His reputation was made at once; but he seldom quit Savona, though often invited to do so, saving for journeys of pleasure, in which he greatly delighted, and for occasional visits to the courts of princes where he was often summoned for his verse's sake and in his capacity as a dramatist. At the age of 50 he took a wife, Lelia Pavese, by whom he had no children. After a simple, blameless life, in which he produced a vast quantity of verse — epic, tragic, pastoral, lyrical and satirical — he died in Savona on 14 October 1638. An elegant Latin epitaph was written for him by [[Pope Urban VIII]],<ref>Siste Hospes./Gabrielem Chiabreram vides;/Thebanos modos fidibus Hetruscis/adaptare primus docuit:/Cycnum Dircaeum/Audacibus, sed non deciduis pennis sequutus/Ligustico Mari/Nomen aeternum dedit:/Metas, quas Vetustas Ingeniis/circumscripserat,/Magni Concivis aemulus ausus transilire,/Novos Orbes Poeticos invenit./Principibus charus/Gloria, quae sera post cineres venit,/Vivens frui potuit./Nihil enim aeque amorem conciliat/quam summae virtuti/juncta summa modestia.</ref> but his tombstone bears two quaint Italian [[hexameter]]s of his own, warning the gazer from the poet's example not to prefer [[Mount Parnassus|Parnassus]] to [[Calvary]].<ref name="EB1911"/> |

||

| ⚫ | A maker of odes in |

||

==Works== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | A maker of odes in their elaborate pomp of [[strophe]] and [[antistrophe]], a master of new, complex [[meter (poetry)|rhythms]], a coiner of ambitious words and composite [[epithet]]s, an employer of audacious transpositions and inversions, and the inventor of a new system of poetic diction, Chiabrera was compared with Ronsard. Both were destined to suffer eclipse as great and sudden as their glory. Ronsard was succeeded by [[François de Malherbe|Malherbe]] and by French literature, properly so-called; Chiabrera was the last of the great Italians, after whom literature languished till a second renaissance under [[Alessandro Manzoni|Manzoni]]. Chiabrera, however, was a man of merit, not just an innovator. Setting aside his epics and dramas (one of the latter was honoured with a translation by [[Nicolas Chrétien]], a sort of scenic [[du Bartas]]), much of his work remains readable and pleasant. His grand [[Pindarics]] are dull, but some of his Canzonette, like the anacreontics of Ronsard, are elegant and graceful. His autobiographical sketch is also interesting. The simple poet, with his adoration of Greek (when a thing pleased him greatly he was wont to talk of it as "Greek Verse"), delight in journeys and sightseeing, dislike of literary talk save with intimates and equals, vanities and vengeances, pride in remembered favours bestowed on him by popes and princes, ''infinita maraviglia'' over [[Virgil]]'s versification and metaphor, fondness for [[masculine rhyme]]s and [[blank verse]], and quiet [[Christianity]]: all this may deserve more study than is likely to be spent on that "new world" of art which it was his glory to fancy his own, by discovery and by conquest.<ref name="EB1911"/> |

||

Giambattista Marino was a contemporary of Chiabrera whose verses provide a comparison.<ref>{{Cite book |title=A History of the Oratorio: Vol. 1: The Oratorio in the Baroque Era: Italy, Vienna, Paris Centuries |author=Smither, Howard E. |date=September 2012 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=am-kgHq_gUC&q=%22giovan%2Bbattista%2Bmarino%22%2B%22gabriello%2Bchiabrera%22%2B%22for%2Ba%2Bbrief%2Bsurvey%2Bin%2Bitalian%2Bof%2Bthese%2Btwo%2Bstyles%22&pg=PA155 |page=155 |isbn=9780807837733 |access-date=2016-07-31}}</ref> |

|||

Giambattista Marino was a contemporary of Chiabrera whose verses provide a comparison.<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|title=A History of the Oratorio: Vol. 1: The Oratorio in the Baroque Era: Italy, Vienna, Paris Centuries |

|||

|author=Smither, Howard E. |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=am-hkgHq_gUC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155&dq=Marino+contemporary+of+Chiabrera&source=bl&ots=tcxXLQc8LI&sig=ElD80o4P3OHEqK8hoM4NXwJxwfQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjQqtWywpzOAhXIn5QKHWmKAUcQ6AEIJzAC#v=onepage&q=Marino%20contemporary%20of%20Chiabrera&f=false |

|||

|page=155 |

|||

|accessdate=2016-07-31}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 23: | Line 38: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

* {{cite journal|last=Rossi|first=P.|year=2002|title=Chiabrera, Gabriello|journal=The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|access-date=7 June 2023|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198183327.001.0001/acref-9780198183327-e-762}} |

|||

* {{Gutenberg author |id= |

* {{Gutenberg author |id=5875|name=Gabriello Chiabrera}} |

||

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Gabriello Chiabrera}} |

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Gabriello Chiabrera}} |

||

* {{treccani|gabriello-chiabrera|Gabriello Chiabrera||1931}} |

* {{treccani|gabriello-chiabrera|Gabriello Chiabrera||1931}} |

||

* {{DBI |title= CHIABRERA, Gabriello |url=http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/gabriello-chiabrera_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/|last= Merola|first= Nicola|volume= 24}} |

* {{DBI |title= CHIABRERA, Gabriello |url=http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/gabriello-chiabrera_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/|last= Merola|first= Nicola|volume= 24}} |

||

* {{cite book |title= The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature |url=https://archive.org/details/classicaltraditi00high |url-access= registration |last= Highet|first= Gilbert |author-link=Gilbert Highet |publisher= [[Oxford University Press, USA]] |year=1949 |isbn=9780198020066 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/classicaltraditi00high/page/235 235]-236, 245-246}} |

* {{cite book |title= The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature |url=https://archive.org/details/classicaltraditi00high |url-access= registration |last= Highet|first= Gilbert |author-link=Gilbert Highet |publisher= [[Oxford University Press, USA]] |year=1949 |isbn=9780198020066 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/classicaltraditi00high/page/235 235]-236, 245-246}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Giordano|first=Paolo A.|title=Gabriello Chiabrera|editor1=Gaetana Marrone|editor2=Paolo Puppa|journal=Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies|url=https://books.google. |

* {{cite journal |last=Giordano|first=Paolo A.|title=Gabriello Chiabrera|editor1=Gaetana Marrone|editor2=Paolo Puppa|journal=Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d9NcAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA455|pages=455–458|publisher=[[Routledge]]|isbn=9781135455309|year=2006}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 37: | Line 53: | ||

[[Category:1552 births]] |

[[Category:1552 births]] |

||

[[Category:1638 deaths]] |

[[Category:1638 deaths]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Italian male poets]] |

[[Category:Italian male poets]] |

||

[[Category:People from Savona]] |

[[Category:People from Savona]] |

||

[[Category:17th-century Italian dramatists and playwrights]] |

[[Category:17th-century Italian dramatists and playwrights]] |

||

[[Category:17th-century Italian male writers]] |

|||

[[Category:Italian male dramatists and playwrights]] |

|||

[[Category:Italian-language poets]] |

[[Category:Italian-language poets]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Baroque writers]] |

|||

[[Category:Italian Baroque people]] |

|||

Revision as of 03:16, 20 March 2024

Gabriello Chiabrera | |

|---|---|

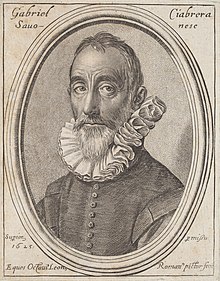

Ottavio Leoni, Gabriello Chiabrera, 1625, engraving and stipple in laid paper, Washington, National Gallery of Art | |

| Born | 18 June 1552 Savona, Republic of Genoa |

| Died | 14 October 1638 (aged 86) Savona, Republic of Genoa |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | Italian |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Period | Late Middle Ages |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Notable works | Canzonette Il rapimento di Cefalo Orfeo dolente |

| Spouse | Lelia Pavese |

Gabriello Chiabrera (Italian pronunciation: [ɡabriˈɛllo kjaˈbrɛːra]; 18 June 1552 – 14 October 1638) was an Italian poet, sometimes called the Italian Pindar.[1] His "new metres and a Hellenic style enlarged the range of lyric forms available to later Italian poets."[2]

Biography

Chiabrera was of patrician descent and born at Savona, a little town in the domain of the Genoese republic, 28 years after the birth of Pierre de Ronsard, with whom he has more in common than with the great Greek whose echo he sought to make himself. As he states in a pleasant fragment of autobiography prefixed to his works, where like Julius Caesar he speaks of himself in the third person, he was a posthumous child; he went to Rome at the age of nine, under the care of his uncle Giovanni. There he read with a private tutor, suffered severely from two fevers in succession, and was sent at last, for the sake of society, to the Jesuit College, where he remained till his 20th year, studying philosophy, as he says, "rather for occupation than for learning's sake".[1]

Losing his uncle about this time, Chiabrera returned to Savona, "again to see his own and be seen by them." A little while later he returned to Rome and entered the household of a cardinal, where he remained for several years, frequenting the society of Paulus Manutius and of Sperone Speroni, the dramatist and critic of Tasso, and attending the lectures and hearing the conversation of Muretus. His revenge of an insult offered him obliged him to betake himself once more to Savona, where, to amuse himself, he read poetry, and particularly Greek.[1]

Poets of his choice were Pindar and Anacreon. These he studied until it became his ambition to reproduce in his own tongue their rhythms and structures and to enrich his country with a new form of verse, and "like his country-man, Columbus, to find a new world or drown." His reputation was made at once; but he seldom quit Savona, though often invited to do so, saving for journeys of pleasure, in which he greatly delighted, and for occasional visits to the courts of princes where he was often summoned for his verse's sake and in his capacity as a dramatist. At the age of 50 he took a wife, Lelia Pavese, by whom he had no children. After a simple, blameless life, in which he produced a vast quantity of verse — epic, tragic, pastoral, lyrical and satirical — he died in Savona on 14 October 1638. An elegant Latin epitaph was written for him by Pope Urban VIII,[3] but his tombstone bears two quaint Italian hexameters of his own, warning the gazer from the poet's example not to prefer Parnassus to Calvary.[1]

Works

A maker of odes in their elaborate pomp of strophe and antistrophe, a master of new, complex rhythms, a coiner of ambitious words and composite epithets, an employer of audacious transpositions and inversions, and the inventor of a new system of poetic diction, Chiabrera was compared with Ronsard. Both were destined to suffer eclipse as great and sudden as their glory. Ronsard was succeeded by Malherbe and by French literature, properly so-called; Chiabrera was the last of the great Italians, after whom literature languished till a second renaissance under Manzoni. Chiabrera, however, was a man of merit, not just an innovator. Setting aside his epics and dramas (one of the latter was honoured with a translation by Nicolas Chrétien, a sort of scenic du Bartas), much of his work remains readable and pleasant. His grand Pindarics are dull, but some of his Canzonette, like the anacreontics of Ronsard, are elegant and graceful. His autobiographical sketch is also interesting. The simple poet, with his adoration of Greek (when a thing pleased him greatly he was wont to talk of it as "Greek Verse"), delight in journeys and sightseeing, dislike of literary talk save with intimates and equals, vanities and vengeances, pride in remembered favours bestowed on him by popes and princes, infinita maraviglia over Virgil's versification and metaphor, fondness for masculine rhymes and blank verse, and quiet Christianity: all this may deserve more study than is likely to be spent on that "new world" of art which it was his glory to fancy his own, by discovery and by conquest.[1]

Giambattista Marino was a contemporary of Chiabrera whose verses provide a comparison.[4]

References

- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chiabrera, Gabriello". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 117. Endnote: The best editions of Chiabrera are those of Rome (1718, 3 vols. 8vo); of Venice (1731, 4 vols. 8vo); of Leghorn (1781, 5 vols., 12mo); and of Milan (1807, 3 vols. 8vo). These only contain his lyric work; all the rest he wrote has been long forgotten.

- ^ Jarndyce Catalogue No. CCLI, London, Autumn 2021, Item 134.

- ^ Siste Hospes./Gabrielem Chiabreram vides;/Thebanos modos fidibus Hetruscis/adaptare primus docuit:/Cycnum Dircaeum/Audacibus, sed non deciduis pennis sequutus/Ligustico Mari/Nomen aeternum dedit:/Metas, quas Vetustas Ingeniis/circumscripserat,/Magni Concivis aemulus ausus transilire,/Novos Orbes Poeticos invenit./Principibus charus/Gloria, quae sera post cineres venit,/Vivens frui potuit./Nihil enim aeque amorem conciliat/quam summae virtuti/juncta summa modestia.

- ^ Smither, Howard E. (September 2012). A History of the Oratorio: Vol. 1: The Oratorio in the Baroque Era: Italy, Vienna, Paris Centuries. p. 155. ISBN 9780807837733. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Gabriello Chiabrera". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Gabriello Chiabrera". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- Rossi, P. (2002). "Chiabrera, Gabriello". The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- Works by Gabriello Chiabrera at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Gabriello Chiabrera at Internet Archive

- Gabriello Chiabrera entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia italiana, 1931

- Merola, Nicola (1980). "CHIABRERA, Gabriello". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 24: Cerreto–Chini (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Highet, Gilbert (1949). The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 235-236, 245–246. ISBN 9780198020066.

- Giordano, Paolo A. (2006). Gaetana Marrone; Paolo Puppa (eds.). "Gabriello Chiabrera". Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies. Routledge: 455–458. ISBN 9781135455309.