ʿAin Ghazal

Coordinates: 31 ° 35 ′ 0 ″ N , 36 ° 20 ′ 0 ″ E

ʿAin Ghazal ( Arabic عين غزال) is an early Neolithic settlement at the source of the Nahr ez-Zarqa river near Amman in Jordan . The settlement was around from 7300 BC. Until 5000 BC Inhabited and is one of the earliest sites of an agricultural society. With an area of around 15 hectares, ʿAin Ghazal is one of the largest prehistoric settlements in the Middle East . Due to extensive finds of house floor plans, graves, devices, botanical remains, animal bones and the like, it is possible to reconstruct the everyday life of the people of ʿAin Ghazal. Since the place remained populated for over 2000 years due to larger water resources, changes in the way of life of these people can also be observed over 100 generations.

Research history

The remains of ʿAin Ghazal have remained intact for around 7,000 years since the settlement was abandoned until the site was cut in 1974 when a motorway was built. The importance of the site was only recognized in 1981, when bulldozers uncovered architectural remains and graves. In 1982 the Jordanian Antiquities Authority began a rescue excavation when the new motorway was already 600 meters through the site. Students from the Jordanian universities and numerous volunteers from business and diplomacy took part in this rescue excavation. When the enormous spatial extent of ʿAin Ghazal became known in this way, plans arose for a multi-year excavation program, for which the Yarmuk University in Irbid initially assumed responsibility in 1983 . The Desert Research Institute in Reno ( Nevada ) and the National Geographic Society in the USA provided generous financial support for a period of five years .

During the 1983 campaign, the excavation area was expanded, uncovering architectural remains and the landfill of four male skulls bearing remains of over-modeling. In the summer of the same year, the first of two hoards so far that contained anthropomorphic circular images made of limestone was discovered. This made ʿAin Ghazal internationally famous. The statues were recovered together with the earth as a coherent block and conserved by the Institute of Archeology in London . Five of the 26 figures could also be restored .

In the following year, the excavation areas were expanded in order to gain new knowledge about the settlement history of ʿAin Ghazal. Here it was possible to prove that the size of the settlement was inhabited for over two millennia and that many other villages in the southern Levant survived. A second hoard with figures was also discovered, which, however, had been severely damaged by the construction work on the motorway. In 1985 this was also recovered as a block of earth and sent to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC for conservation . There it was possible to restore three two-headed statues.

In 1988/89 the later settlement history moved into the center of the efforts, whereby it was established that from about 5500 BC onwards. The previously common two-story apartment buildings were replaced by single family houses, which suggests a decline in the population. Further excavations from 1992 to 1998 concentrated more on the peripheral areas of the settlement, which again demonstrated its enormous extent. In addition to the remains of an extension of the place east of the Zarqa, stone settlements were uncovered that suggest very long walls. Such long walls have not yet been found in the western main settlement. In 1993 the existence of two-story buildings was clearly established. In addition, smaller buildings were found that are interpreted as shrines. In 1995, a sanctuary was also uncovered, which had a 20 meter long protective wall and an altar and a fireplace inside. A similar building was discovered the following year in the eastern part of the settlement.

Settlement history

Settlement periods

- 7250-6500 BC Chr .: middle pre-ceramic Neolithic B (mPPNB)

- 6500-6000 BC Chr .: late pre-ceramic Neolithic B (sPPNB)

- 6000-5500 BC Chr .: pre-ceramic Neolithic C (PPNC)

- 5500-5000 BC Chr .: ceramic Neolithic (PN)

art

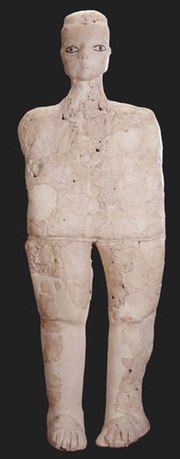

In the past few decades, numerous spectacular examples of art have been discovered on the fringes of the fertile crescent . These include over 30 sculptures from ʿAin Ghazal, which were made in the early 7th millennium BC. Were made. Some of the statues are on display in the Jordan Museum in Amman .

Face masks

The oldest sculptures in ʿAin Ghazal date from the 8th millennium BC. BC and are thus the oldest known, round, life-size sculptures. These are three face masks that are considered the forerunners of the full-body statues. It is now believed that the majority of the dead were buried outside of settlements, with very few buried under the floors of residential buildings. In ʿAin Ghazal, the graves of the latter were probably reopened and their skulls removed. According to Michelle Bonigofsky, scratches on a skull could result from an intentional roughening of the surface, which should promote better adhesion of the plaster of paris. These skulls were then over-modeled with masks, the facial features of the deceased presumably not being reproduced. The missing lower jaw resulted in a widened face shape. The eyes are shown closed, but accentuated by bitumen inlays.

Statues

The statues themselves were made around 6700 BC. Disordered (Hort 1; 1983) or 6500 BC. Chr. (Hort 2; 1984) deposited in uninhabited houses. Their size ranges from small formats to almost life-size plastic. The older figures are characterized by particularly emphasized body shapes and colored painting; they were equipped with an eyeball made of white lime and a bitumen insert for the eyelids and the iris. The later figures have a somewhat clumsier and undecorated body. These have almond-shaped pupils. In addition, among them were also three double-headed busts with flat, board-like bodies and finely worked faces. Presumably, the figures served some kind of ancestral cult and were erected before they were buried face down in pits after a while. The statues are made entirely of a mixture of burnt lime and clay. The mastery of the technique of lime burning led to the classification of ʿAin Ghazal in the akeramischen Neolithic B; at this time the technique of lime burning was known. Pottery , on the other hand, was only used from around 5500 BC Manufactured. This mixture was modeled around an inner skeleton made of bundles of reeds that protruded through the feet from the legs and indicated that the figure was attached to a surface.

literature

- Gary O. Rollefson, Zeidan Kafafi: A farming village is developing: The archaeological treasures of the Neolithic settlement ʿAin Ghazal. In: Beate Salje, Nadine Riedl, Günther Schauerte (eds.): Faces of the Orient: 10,000 years of art and culture from Jordan. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2004, pp. 37–43, ISBN 978-3-8053-3375-7

- Beate Salje: The statues from ʿAin Ghazal - encounter with figures from a bygone world. In: Beate Salje, Nadine Riedl, Günther Schauerte (eds.): Faces of the Orient: 10,000 years of art and culture from Jordan. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2004, pp. 30-36, ISBN 978-3-8053-3375-7

- Reena Perschke: Head and Body - The "Skull Cult" in the Near Eastern Neolithic. In: Nils Müller-Scheeßel (Ed.): "Irregular" burials in prehistory: norm, ritual, punishment ...? Files from the international conference in Frankfurt a. M. from February 3 to 5, 2012 (Bonn 2013) 95–110.

Web links

- Gary O. Rollefson, Allan H. Simmons, Zeidan Kafafi: Neolithic Cultures at ʿAin Ghazal, Jordan. (PDF; 5.6 MB) Journal of Field Archeology 19/4, 1992, pp. 443-470.