Alexandre de Rieux, Marquis de Sourdéac

Alexandre, sieur de Rieux, Prince de la Maison de Bretagne, marquis de Sourdéac, Neufbourg, Ouestant et Coëtmeur (* 1619 , † May 7, 1695 in Amsterdam ) was a Breton nobleman , well-known set designer and theater machinist who helped found the Parisians Opera was involved.

Life

Voltaire wrote of him that he loved the arts too much, died impoverished and ruined after launching opera in French . In an obituary, the Gazette d'Amsterdam claimed that he was the first to receive a theater patent for Paris from Louis XIV , which is not the case - in fact, the patent went to Pierre Perrin . Some people also believed that this was just a cover name that Rieux chose to avoid associating his family with this kind of business.

Alexandre was the eldest son of Gui de Rieux and Louise de Vieux-Pont. He was characterized by craftsmanship and an interest in mechanics. The stage machinery, which was developing rapidly at the time, offered him an ideal field of activity. In 1660 he produced Pierre Corneilles La Toison d'or (The Golden Fleece) at his castle in Neubourg . He then bequeathed the stage technology he manufactured to the committed Parisian company Théâtre du Marais. In 1662 in the largest theater of the time, the Théâtre des Tuileries , he handled the theater machines for the performance of Francesco Cavalli's opera Ercole amante . Sourdéac left his wife in the country with 13 children, lived in Paris from 1667 and soon made the acquaintance of Laurent Bersac.

On June 28, 1669, Pierre Perrin received a privilege from King Louis XIV to found the “Académie d'Opéra”, to which he chose Alexandre de Rieux and his steadfast companion Laurent Bersac, son of a simple sergeant, who was “ Fondant de Champeron “and had previously worked as an informant and bailiff. Rieux was of genuine, old Breton nobility, but had a reputation as a murderer and pirate on the local coast, as a usurer, counterfeiter and thief. What made him useful to Perrin was his ability to operate stage machinery and the means to set up a theater.

Already at the beginning of the project Perrin had problems with a creditor, the Parliamentary Councilor Gabriel Bizet de La Barroire, could not contribute anything to the financing of a theater facility, but had the idea that the society in which he was artistic director together with Robert Cambert should bring him should refurbish financially. This worked for three months, until the balance of power was rearranged by Rieux and Bersac: Cambert became a simple employee and the not particularly business-minded Perrin no longer played a role - only his name counted as the holder of the privilege. The fact that their opera Pomone was an incredible success and each of the 146 performances brought in 1,000 to 4,000 livres was of little use to the artistic directors. Perrin filed a complaint against his business partners on May 9, 1671, but was imprisoned in the Conciergerie on June 15 at the instigation of de La Barroire . The effect of his own complaint against Rieux and Bersac was then apparently misjudged by him: He said that he could now proceed with his privilege at his own discretion and sell it. The buyer was the composer Jean de Granouilhet, écuyer sieur de Sablières, "intendant de la musique de Monsieur ". In December 1671, Sablières teamed up with Henri Guichard to exploit the privilege , to whom he sold half of his rights.

The privilege granted by the king, which was supposed to enjoy a certain reputation, was now lost in the rights-dealing of people who were sometimes in prison or who had already had relevant experience. So it came about that the privilege granted by Louis XIV was withdrawn and Jean-Baptiste Lully , who had previously visited Perrin in the Conciergerie, bought the privilege and helped him to freedom, became the new director of the Opera Academy.

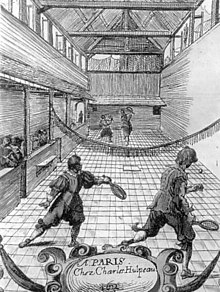

Sourdéac is often portrayed as someone who liked to hang out in pubs and brothels, who, despite his wife and daughters, took prostitutes into his house and was incessantly gossiping and swearing. In 1672 he always had reason for this. The theater he set up for Pomone in the Jeu de paume de Béquet was closed by the police before the premiere - Perrin had forgotten to apply for a permit. The second opera house in the Jeu de paume de la Bouteille, Petite-rue de Nesle (or 42, rue Mazarine) soon felt the same after Pomone when Lully was unwilling to pay the excessive price that Sourdéac and Champeron were asking for it . Sourdeác wanted 30,000 livres for the hall, 14,000 of them immediately. The ballroom, which was converted into a theater in 1670, was finally rented by La Grange for Molière's orphaned troupe and thus became the cradle for the Comédie-Française . La Grange borrowed the money from Molière's brother-in-law, André Boudet. The house was given a different name and, reinforced by the best people at the Théâtre du Marais, it was now called “La Troupe du roi à l'Hôtel Guénégaud”. The first play was the Tartuffe , the Mercure gallant did not skimp on praise, even for the builder of the theater - probably not without ulterior motives from the editors Donneau de Visé and Thomas Corneille . The latter saw his Circé performed from the stage in 1674 with Sourdéac as a theater machinist. Alexandre de Rieux, Marquis de Sourdéac died impoverished.

literature

- Armand Jardillier: La Vie originale de Monsieur de Sourdéac , A. & J. Picard, Paris 1961

Web links

- Literature by and about Alexandre de Rieux, Marquis de Sourdéac in the bibliographic database WorldCat

Individual evidence

- ↑ Louis E. Auld: The Lyric Art of Pierre Perrin, Founder of French Opera. Part 1. Birth of French Opera , Henryville – Ottawa – Binningen 1986, ISBN 0-931902-28-2 , p. 45.

- ^ A b Louis E. Auld: The Lyric Art of Pierre Perrin, Founder of French Opera. Part 1. Birth of French Opera , Henryville et al. 1986, p. 46.

- ↑ Jean-Claude Brenac: Perrin et Cie: drôle d'associés! , Website “operabaroque.fr”, July 2005

- ^ Johannes Hösle: Molière. His life, his work, his time , Piper Verlag, Munich 1987, p. 301.

- ↑ Jérôme de La Gorce: L'Opéra à Paris au temps de Louis XIV. Histoire d'un théâtre , Paris 1992, p. 18 u. 30th

- ↑ Jérôme de La Gorce: L'Opéra à Paris au temps de Louis XIV.Histoire d'un théâtre , Paris 1992, p. 20.

- ↑ Jérôme de La Gorce: L'Opéra à Paris au temps de Louis XIV.Histoire d'un théâtre , Paris 1992, p. 18.

- ↑ Jérôme de La Gorce: L'Opéra à Paris au temps de Louis XIV.Histoire d'un théâtre , Paris 1992, p. 21.

- ↑ Jérôme de La Gorce: L'Opéra à Paris au temps de Louis XIV.Histoire d'un théâtre , Paris 1992, p. 26.

- ↑ Jérôme de La Gorce: L'Opéra à Paris au temps de Louis XIV.Histoire d'un théâtre , Paris 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Johannes Hösle: Molière. His life, his work, his time , Piper Verlag, Munich 1987, p. 302.

- ↑ a b c d Emmanuel Haymann: Lulli , Flammarion, Paris 1991, p. 157 f.

- ^ Johannes Hösle: Molière. His life, his work, his time , Piper Verlag, Munich 1987, p. 338.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rieux, Alexandre de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sourdéac |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French set designer, contributor to the founding of the Paris Opera |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1619 |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 7, 1695 |

| Place of death | Amsterdam |