Anamorphic procedure

The anamorphic method is a way of recording films with specially designed camera optics, the anamorphic ones . Its purpose is to create a particularly wide image that is closer to human perception than, say, the 4: 3 film format. Instead of cropping the image above and below and thereby losing resolution, the anamorphic lenses distort towards the edge. Corresponding equalization then takes place during playback.

The process has become the standard for cinema films under the protected brand name “ CinemaScope ” of the 20th Century Fox Film Corporation, which stands for the special camera and projection lenses , the actual process and the films and video projections made with it. In technical jargon , “CS” or “Scope” for short has also become established. However, there are also other names used by other film companies or manufacturers with similar or similar processes . The process has been experiencing a revival since around 2016 due to the increasingly better quality of smartphone cameras. No anamorphic projector rectifies the compressed image, but an app on the device.

functionality

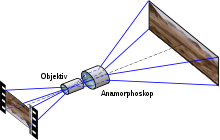

With the help of an anamorphic lens or prism construction ( anamorphic or anamorphoscope) in front of the camera lens, the horizontal image is additionally reduced by the anamorphic factor compared to the vertical (usually by a factor of 2). This creates a picture that is "compressed" in width. When projecting in the cinema, the film projector is given a similar anamorphic lens , which "pulls apart" the width of the image by the same factor. This gives the image the original, undistorted proportions of the filmed object.

However, it is not always necessary to use similar anamorphic anamorphic lenses in front of the camera for distortion and for projection to correct the distortion; a distinction must be made between the production format (negative when recording with the camera) and the distribution format (screening copy). For example, in the Techniscope process, an undistorted full wide image is recorded on the negative with the camera. The anamorphic distortion is only made when copying onto the demonstration positive. Conversely, in modern digital film production with an anamorphic lens in front of the camera lens, a compressed widescreen image can be recorded on a normal-format chip with an aspect ratio of 1.33: 1 and the rectification can be carried out in the course of digital image processing or only at the end through the widescreen screen without the Reproduction an anamorphic is necessary.

An advantage of the anamorphic method is that a wide image can be projected with inexpensive standard material (for example 35 mm film ). There are also non-anamorphic alternatives, such as 70 mm film or the Cinerama process, which, however, have significantly higher material costs and also require special projectors.

Another advantage is that the light from the projector lamp is better used. Cinema projectors are equipped with rotationally symmetrical ellipsoidal mirrors, which thus also illuminate a circular area on the film window. Optimal use of the light would therefore be obtained with a square image (aspect ratio 1: 1) on the film strip. The anamorphic compressed format 1.175: 1 comes closer to the theoretical optimum than the rectified widescreen aspect ratio of 2.35: 1. In fact, the Superscope and now IMAX methods use square image windows.

The disadvantage of the anamorphic method consists in the more complicated recording and projection optics. Inadequate adjustment of the recording or playback lenses can result in display errors. Larger film screens also had to be set up for widescreen projection.

history

The idea of anamorphism did not originate in the film industry, but was used as early as the Middle Ages to encode fonts or, especially in the 17th century, for the corrected perception of paintings on vaults (see the articles on anamorphosis and anamorphic ).

The anamorphic process found its way into the film and cinema world in the 1950s. From the second half of the 1940s, this was preceded by the fact that 3D films were very popular in the cinema. However, these methods were very inconvenient for the viewer to wear glasses and also very expensive to produce, and attempts were made to replace the impression of three-dimensional representation with a projection with a very wide aspect ratio on a curved screen ( Cinerama ). However, it was falsely advertised that it was a new 3D process. But this too was always very expensive and, above all, incompatible with the established projection technology in cinemas.

In this competitive situation, 20th Century Fox remembered the anamorphic process invented by Henri Chrétien around 1927, acquired technology and optical know-how from him in 1952 and launched it in 1953 under the CinemaScope brand. The monumental Bible film Das Gewand (The Robe) premiered on September 16, 1953 in New York as the first full-length feature film to be produced using this technology. It was advertised as a film "that can be seen vividly without glasses". Again, as with Cinerama, the viewer was suggested that he would see a 3D film, even though it was a fairly wide, but actually two-dimensional projection.

The production and projection of films with hi-fi multichannel sound for widescreen presentation using the anamorphic process was relatively inexpensive, and by 1955 more than 60% of all cinemas in the United States were technically capable of showing anamorphic widescreen films. The anamorphic process had established itself on a broad front in just a few years, and the three-dimensional process had been pushed into a niche existence. In addition to 20th Century Fox, other large film companies soon also produced anamorphic films, initially often taking over camera technology and the CinemaScope brand under license from 20th Century Fox, which contributed to the widespread use of the brand as a name for the process as such. In the late 1950s in particular, the film companies began to close their own camera technology departments and use cameras with optics from manufacturers such as Arnold & Richter (ARRI) or Panavision , thereby changing their licensing policy. Subsequently, films made anamorphically with an aspect ratio of 2.35: 1 (or 2.4: 1) have appeared under other brand names or occasionally simply with the reference to “lens by Panavision”, which from 1957 onwards high-quality anamorphic camera optics posed.

In Europe, the terms “ Ultrascope ” and “Totalvision” were also used for anamorphic films .

The first real 3D film in CinemaScope was The Treasure of the Balearic Islands by director Byron Haskin . The first anamorphic animated cartoon was the Walt Disney production Die Musikstunde ( Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom ), premiered on November 1, 1953.

Formats for 35mm film

Assuming an aspect ratio of the Academy film image of 1.375: 1, the usual anamorphic factor of 2 should result in an aspect ratio of 2.75: 1. In practice, however, this is not the case because anamorphic cinema films use a different image format on the film. On the one hand, the image window is slightly larger than the normal format, which benefits the sharpness of the projected image. The image area of the film strip is thus used to the maximum and part of the film material does not remain unused - as is the case with non-anamorphic wide-screen processes with lamination, for example. However, this also makes the image line narrower, which sometimes makes unclean negative glue areas visible.

Furthermore, the image field is narrowed in width by the sound track, so that when recording with optical sound on the film, an aspect ratio of 1.175: 1 is created. This in turn results in the anamorphic factor 2 on the screen, the well-known aspect ratio of 2.35: 1. With the earlier four-channel magnetic sound (COMMAG), the aspect ratio was 2.55: 1 on the screen due to the lack of space required for the optical sound track (films up to 1957).

However, confusion often remains about the exact width of the anamorphic aspect ratio, which is given as either 2.35, 2.39 or 2.4 to 1, although the anamorphic factor of the optics used is almost always exactly 2. The deviations are due to differences in the camera and projection masks. This is further complicated by the SMPTE standards for the film format, which have changed over time.

The original definition of the SMPTE for anamorphic projection with an optical sound track on one side (PH22.106-1957), issued in December 1957, standardized the projector mask with 0.839 × 0.715 inches (aspect ratio 1.17: 1). The aspect ratio for this mask, after the 2 × distortion, is 2.3468 ...: 1, which has normally been rounded to the common value of 2.35: 1 . A new definition from October 1970 (PH22.106-1971), which specifies a slightly flatter 0.7 inch mask for the projector, should help to make the splices less visible. Anamorphic film copies use more of the film surface than all other formats and leave very little space for the splices, which can lead to bright flashes of light during the presentation. For this reason, demonstrators had already reduced the projection vertically before the release of PH22.106-1971. This new projection mask measuring 0.838 × 0.7 inches (21.3 × 17.8 mm), aspect ratio 1.1971 ...: 1, resulted in an aspect ratio of 2.39: 1, which was often rounded to 2.4: 1 . The latest version, from August 1993 (SMPTE 195-1993), changed these dimensions slightly again so that the mask width for anamorphic 2.39: 1 and non-anamorphic 1.85: 1 together was 0.825 inches (21 mm) . The projector mask was also reduced by 0.01 inches, and is now 0.825 × 0.69 inches (21 × 17.5 mm), aspect ratio 1.1956 ...: 1 (often rounded to 1.2: 1) Maintain aspect ratio of 2.39: 1.

Anamorphic copies are still often referred to as “2.35” by projectionists, cameramen and others in the film industry. Unless they are about films from 1958 to 1970, they describe films with an actual aspect ratio of 2.39: 1. With the exception of a few specialists and archivists, they often mean the same thing, regardless of whether they speak of 2.35 or 2.39 or 2.40.

Anamorphic processes in cine film

The anamorphic process is also rarely used in cine films, mostly for the production of cine film copies of anamorphic 35 mm movie originals. Only in exceptional cases, however, are narrow films shot directly using the anamorphic method.

With 8 mm films , anamorphic lenses are used, which - unlike 35 mm film - have an anamorphic factor of 1.5. Above all, this lower value results in smaller dimensions and, as a result, a lower weight of the lens attachments to be used, which is of great importance for the very mobile, lightweight 8 mm cine film cameras. As a result, however, these films are not compatible with other films produced using the anamorphic process and cannot easily be copied to another format.

For the recording of 16 mm films , on the other hand, converted anamorphic lenses from the 35 mm range are mainly used, which work with the factor 2 that is customary there. Since the same image windows are used on the film for both normal-format and anamorphic recordings, this results in an aspect ratio of 2.66: 1 in the projection.

Terms and related procedures

After the successful introduction of the anamorphic process by 20th Century Fox, other film companies endeavored to use it as well without having to pay license fees. As a result, a number of brand names emerged, which, however, technically stood for the same process on 35 mm film. The anamorphic lenses were constructed differently, but had the same anamorphic factor 2 and the films produced were compatible:

- Cinemascope , the original process

- Ultrascope

- Total vision

- Cinépanoramic / Camerascope / Naturama / Franscope

- Vistarama

- Hammerscope / Byronscope

The systems of:

In these, an undistorted image was recorded with the camera without an anamorphic lens. The anamorphic widescreen image was only created when copying onto the projection positive. At Superscope the negative was in normal format and was trimmed in height during anamorphic copying, at Techniscope the negative was already a wide image. The anamorphic screening copies of these two processes were compatible with those of the aforementioned in the projection.

However, the films under the names required their own projection technology

because they were partly based on broader film material and had fewer anamorphic factors.

Of the above, the wide-screen processes with the designations

completely different. These are not anamorphic processes, as the widescreen image is already present undistorted on both the negative and the screening copy and therefore an anamorphic image is not necessary either on the camera or on the projector.

See also

literature

- CinemaScope. The third revolution in the field of film. Everything you need to know about the new process for recording and playing back plastic films . Published by the central press and advertising department of Centfox-Film-Inc., Frankfurt / Main, Kirchnerstrasse 2, undated; 1953, paperback, 32 p. Without cover

- CinemaScope. The color film on a large picture with a three-dimensional effect - without the use of glasses . Published by the central press and advertising department of Centfox-Film-Inc., Frankfurt / Main, Kirchnerstraße 2, undated (1953), paperback, 24 pp.

- Helga Belach, Wolfgang Jacobsen (Hrsg.): CinemaScope - On the history of wide screen films . Deutsche Kinemathek / Spiess Foundation , 1993, ISBN 3-89166-646-2

Web links

- American Widescreen Museum (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Official trademark register of the German Patent and Trademark Office ( https://register.dpma.de/DPMAregister/Uebersicht )

- ↑ a b WideScreen Format War Begins. American WideScreen Museum, accessed April 30, 2014 .

- ↑ a b Cornelis Hähnel: Films with the divine ether of the poet. On: dradio.de on September 16, 2013

- ^ The CinemaScope Wing 8th American WideScreen Museum, accessed May 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Is there any advantages of going with a 2.40: 1 screen over a 2.35: 1 screen? AVS Forum, accessed on April 11, 2014 (English).

- ^ History of Scope Aspect Ratios. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 11, 2012 ; accessed on April 11, 2014 (English).

- ↑ Facts On The Aspect Ratio. American WideScreen Museum, accessed April 11, 2014 .

- ↑ Of Apertures and Aspect Ratios. American WideScreen Museum, accessed April 11, 2014 .

- ↑ who's in charge. Cinematography.com, accessed April 11, 2014 .