Anarchism in Japan

The anarchism in Japan dates back to the late 19th and early 20th century. The anarchist movement was influenced by the First and Second World Wars , in which Japan played an important role. This movement can be divided into three phases in Japan: from 1898 to 1911, from 1912 to 1936 and from 1945 to today.

history

1898-1911

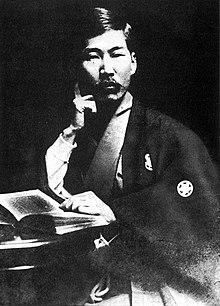

Anarchist ideas were first made known in Japan by the radical journalist Kōtoku Shūsui . After moving to Tokyo as a teenager, Kōtoku became a journalist and from 1898 he wrote for the radical daily Yorozu Chōhō (English: Every Morning News ). His liberalism led him to social democracy and Kōtoku tried in May 1901 to form the first Japanese social democratic party.

His fledgling Social Democratic Party was immediately banned and Yorozu Chōhō shifted his political views away from the left, so that Kōtoku founded his own radical weekly Heimin Shinbun ( Common People's Newspaper ). The first edition appeared in November 1903 and the last in January 1905. His position brought Kōtoku a brief prison sentence from February to July 1905.

In prison he read Peter Kropotkin's Agriculture, Industry and Crafts , and after his release emigrated to the United States , where he joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Kōtoku claimed, “ had gone [to jail] as a Marxian Socialist and returned as a radical anarchist. ”(German:“ to have gone to prison as a Marxist socialist and returned as a radical anarchist. ”) In the USA, more than 50 Japanese immigrants met in Oakland and founded the Social Revolutionary Party . The party began publishing a magazine entitled Kakumei ( German Revolution ) and a leaflet called Ansatsushugi ( German Terrorism ), news of which reached Japan and angered officials there.

Kōtoku returned to Japan in 1906 and spoke at a large public meeting that took place in Tokyo on June 28, 1906, about the ideas he had developed during his stay in the United States (mainly California). These were largely a mix of anarchist communism , syndicalism and terrorism , which developed from reading books such as Kropotkin's Memoirs of a Revolutionary and The Conquest of Bread , among other things . At the meeting, Kōtoku spoke about The Tide of the World Revolutionary Movement and soon began writing numerous articles.

While Kōtoku was in the US, a second social democratic party called the Socialist Party of Japan was formed. In February 1907, that party held a meeting to discuss Kōtoku's views, which eventually led the party to abolish the party rule that required working within the boundaries of the country's law . Five days later, the Japanese Socialist Party was banned.

In 1910 Akaba Hajime wrote a brochure entitled Nômin no Fukuin ( German Gospel of the Peasants ), which spoke of the creation of an anarchist paradise through anarchist communism. His criticism of the Kaiser in the pamphlet causes him to go into hiding, but ultimately he was caught and imprisoned. He died in Chiba Prison on March 1, 1912 .

In the year The Peasants' Gospel was published , four Japanese anarchists were arrested after bomb-making equipment was discovered. This sparked a government crackdown on anarchists, which resulted in 26 anarchists being charged with conspiracy to kill the emperor. The trial was closed to the public and everyone was found guilty. The death penalty provided for this was converted into life imprisonment for twelve convicts.

1912-1936

In 1912 Itō Noe joined the blue stocking company and soon took over the production of the feminist magazine Seito ( German blue stocking ). Itō soon also translated works by the anarchists Peter Kropotkins and Emma Goldman . Itō met and fell in love with Ōsugi Sakae , another Japanese anarchist who had served a number of prison sentences for his activism . Ōsugi began translating and publishing Japanese editions of Kropotkin's Mutual Aid in the Animal and Human Worlds and Memories of a Revolutionary , while he is more personally influenced by the work of Mikhail Bakunin .

Inspired by the 1918 rice riots , Ōsugi began publishing and republishing more of his own writings, such as: B. Studies on Bakunin and Studies on Kropotkin .

The Girochinsha ( German Guillotine Society ) was a Japanese anarchist group from Osaka. This was involved in revenge killings against Japanese leaders in the mid-1920s. Nakahama Tetsu, an anarchist poet and member of the Girochinsha, was executed for his activities.

In 1923 Japan was hit by the great Kanto earthquake . With over 100,000 dead, the state used the riots as an excuse to round up Itō and Ōsugi. According to writer and activist Harumi Setouchi, Itō, Ōsugi and his six-year-old nephew were arrested, beaten to death, and thrown into an abandoned well by a group of military policemen led by Lieutenant Amakasu Masahiko . According to literary scholar Patricia Morley, Itō and Ōsugi were strangled in their cells. This was called the Amakasu Incident and it caused a lot of anger. In 1924 two attacks were made on the life of Fukuda Masatarô, the general in command of the military district in which Itō and Ōsugi were murdered. Wada Kyutaro, an old friend of the deceased, made the first attempt to shoot General Fukuda, but only injured. The second attempt was to bomb Fukuda's house, but the general was not home at the time.

In 1926, two national anarchist associations were formed, the Black Youth League and the All-Japan Libertarian Federation of Labor Unions . In 1927 both groups fought against the death penalty for the Italian-born anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti . In the years that followed, the anarchist movement was marked by an intense debate between anarcho-communists and anarcho-syndicalists . Considered the greatest theoretician of anarchist communism in Japan , Hatta Shūzō began to speak for anarchist communism, claiming that anarchist syndicalism, being a result of the capitalist workplace, would reflect the same division of labor as capitalism. Arguments like those of Shūzō and that of another anarchist named Iwasa Sakutaro convinced the Black Youth League and the All-Japan Libertarian Federation of Labor Unions to move towards anarcho-communism, with anarchist syndicalists leaving both organizations.

These divisions weakened the anarchist movement in Japan, and soon afterwards the Mukden incident caused the state to solidify and silence internal opposition. At the beginning of World War II , all anarchist organizations in Japan were forced to cease their activities.

1945 until today

Shortly after the end of World War II, Ishikawa Sanshirō , who was an anarchist before the war, wrote Gojunen-go-no-Nihon ( German Japan 50 years later ). This work described an anarchist rebuilding of Japanese society after a peaceful revolution. In May 1946 the Japanese Anarchist Federation was established. She published the newspaper Heimin , named after Kōtoku's diary. During this time, Japan was rocked by a wave of workers' demonstrations demanding food and a popular front democratic government . The Federation, however, failed to gain a foothold in the left . Socialists and communists were able to oust the anarchists in social struggles and Heimin became increasingly academic and idealistic. While the anarchists were initially divided in their relations with the Communist Party , Heimin became openly hostile to the party in late 1946. The anarchists opposed a strike prepared by communists, socialists and trade unions for higher pay for government workers. They denounced bureaucrats as agents of authoritarianism and even exposed the strike to the Allied occupation forces, who put an end to this initiative. Eventually the federation split between supporters and opponents of anarcho-syndicalism. In October 1950 she held her 5th conference in Kyôto. Shortly thereafter, the anarcho-syndicalist group ( Anaruko Sanjikarisuto Gurûpu ) split off and the federation de facto ceased to exist, although it was reconstituted in 1951 as an anarcho-syndicalist association. For their part, the anarcho-communists founded the Japanese Anarchist Club ( Nihon Anakisuto Kurabu ). This was a time of crisis for the Japanese left in general. The Communist Party had been banned by the Allies a few months earlier, while many right-wing wartime leaders were able to regain their powerful positions. During the Zenkyõtõ movement in 1968 , which led to student unrest and large anarchist reading and action groups at universities, the Anarchist Federation saw itself as no longer needed and dissolved. In 1988 it was re-established and published the journal Freier Wille ( Jiyû Ishi ). The anarcho-syndicalists have been organized since 1989 in the workers' solidarity movement ( Rôdôsha Rentai Undô ), which is affiliated with the ILO and publishes the magazine Zettai Jiyû Kyôsanshugi (Libertarian Communism).

Japanese anarchists and Korean anarchism

Japanese anarchists collaborated with and supported Korean anarchists. Ōsugi Sakae had a strong influence on the Korean radicals. The Korean anarchist group Heukdo hoe ( German Black Wave Society ) was founded in 1921 with the support of Japanese anarchists. Their newspaper was the Black Wave , whose editor-in-chief was the Korean anarchist Bak Yeol.

Movies

In 2017 the biopic Anarchist from Colony about the anarchist Bak Yeol (also Park Yeol) was published. Director Lee Jun-ik focused on the period from 1923 to 1926, when after the Great Kanto earthquake there were attacks on Koreans in Japan and Park Yeol and Kaneko Fumiko were then imprisoned and charged as scapegoats. Both used the trial to draw attention to the massacre in which around 6,000 Koreans are believed to have been murdered.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Steven: 1868-2000: Anarchism in Japan. In: libcom.org. September 13, 2006, accessed November 13, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac John Crump: The Anarchist Movement in Japan, 1906–1996 . Pirate Press, 1996.

- ↑ Frederick George grade helpers: Shūsui Kōtoku: Portrait of a Japanese Radical . Chapter 4: Pacifist opposition to the Russo-Japanese War, 1903-1905. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1971, LCCN 76-134620 , OCLC 142930 , pp. 106-107 ( google.com ).

- ↑ Shôbee Shiota: Kôtoku Shûsui no Nikki to Shokan . Tokyo 1965, p. 433 .

- ↑ a b A Brief History of Japanese Anarchism. In: ne.jp. Retrieved November 13, 2018 .

- ^ A b Steven: Noe, Ito, 1895-1923. In: libcom.org. February 19, 2006, accessed November 13, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d e Mike Harman: Sakae, Osugi, 1885-1923. In: libcom.org. July 20, 2007, accessed November 13, 2018 .

- ^ John Crump: Hatta Shūzō and Pure Anarchism in Interwar Japan . S. 42 .

- ↑ Helene Bowen Raddeker: Treacherous Women of Imperial Japan: Patriarchal Fictions, Patricidal Fantasies . Routledge , 1997, ISBN 0-415-17112-1 , pp. 131 .

- ↑ Leith Morton: Modernism in Practice: An Introduction to Postwar Japanese Poetry . S. 45-46 .

- ↑ Harumi Setouchi: Beauty in Disarray . Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993, ISBN 0-8048-1866-5 , pp. 18-19 .

- ↑ Patricia Morley: The Mountain is Moving: Japanese Women's Lives . University of British Columbia Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-7748-0675-6 , pp. 19 .

- ↑ Chushichi Tsuzuki: Anarchism . 1970, p. 505-507 .

- ↑ Steven Hirsch, Lucien van der Walt: Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870-1940: The Praxis of National Liberation, Internationalism, and Social Revolution . 2010, p. 102-110 .