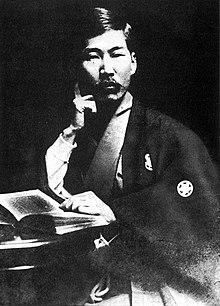

Kōtoku Shūsui

Kōtoku Shūsui ( Japanese 幸 徳 秋水 ; actually 幸 徳 傳 次郎 , Kōtoku Denjirō ; born November 5 or September 23, 1871 in Nakamura ; † January 24, 1911 ) was a socialist and anarchist and played a leading role in the spread of anarchism in Japan in the early 20th century. He translated the works of contemporary European and Russian anarchists such as Kropotkin into Japanese. He was a radical journalist and is often referred to as an anarchist martyr as he was executed by the Japanese government for treason .

Life

Socialist years and imprisonment

Kōtoku went in his middle teenage years from his birthplace Nakamura (now Shimanto ) in Kōchi Prefecture to Tokyo , where he became a journalist in 1893. From 1898 he was a columnist for the Yorozu Chōhō ( 萬 朝 報 ), one of the more radical daily newspapers of that time.

In 1901 he was next to Abe Isoo , Sen Katayama , Kawakami Kiyoshi , Kinoshita Naoe and Nishikawa Kōjirō co-founders of the Shakai Minshutō (Socialist People's Party), which was quickly banned again .

When the Yorozu Chōhō took a supportive position in the Russo-Japanese War in 1903 , he gave up his position. In the following month, together with his colleague Sakai Toshihiko , he founded the “citizens' newspaper” ( “新聞 , Heimin Shimbun ) from the“ civil society ”( 平民 社 , heiminsha ). The anti-war stance repeatedly brought the editors into trouble with the government, and Kōtoku served a five-month prison sentence from February to July 1905 on the pretext of disregarding state press laws.

America and Anarchist Influence

In 1901, when Kōtoku tried to found the Japanese Social Democratic Party with Sakai , he was not an anarchist, but a pacifist social democrat and supported democratic elections. Sakai and Kōtoku translated the Communist Manifesto in the “Bürgerzeitung” and were the first to translate a Marxian work into Japanese. His political attitudes only began to change in a libertarian direction after reading Kropotkin's Agriculture, Industry and Crafts in Prison. In his own words "he went [to prison] as a Marxist socialist and came back as a radical anarchist".

In November 1905, Kōtoku traveled to the United States to openly criticize the Emperor of Japan, whom he saw as the fulcrum of capitalism in Japan. During his time in the United States, Kōtoku became more familiar with the philosophy of anarchist communism and European syndicalism . He had taken Kropotkin's memoirs of a revolutionary with him as reading material for his Pacific trip; after arriving in California, he began correspondence with the Russian anarchist and in 1909 had translated The Conquest of Bread from English into Japanese. A thousand copies of his translation were made in Japan this March and distributed to students and workers.

Return to Japan

When Kōtoku returned to Japan on June 28, 1906, a public meeting was held to welcome him. At this meeting he spoke about "the tides of the revolutionary movement of the world" flowing against the politics of parliamentarism , by which he also meant the party politics of Marxism , and highlighted the general strike as "the means of the future revolution". This was an anarcho-syndicalist point of view and clearly showed American influence, as anarcho-syndicalism was spreading in the US at that time, with the establishment of the Industrial Workers of the World .

He wrote several articles, the most famous of which was "The Change in My Thinking (On Universal Suffrage)". In these articles, Kōtoku propagated direct action rather than political goals such as universal suffrage , which came as a shock to many of his comrades and caused a split between anarcho-communists and social democrats in the Japanese labor movement. The split became clear when he brought out the "Bürgerzeitung" again in 1907, which was replaced two months later by two newspapers: the social democratic newspaper "Soziale Nachrichten" and the "Bürgerzeitung Ōsaka" ( 大阪 平民 新聞 , Ōsaka heimin shimbun ), which from pleaded for direct action from an anarchist perspective.

Although most anarchists preferred nonviolent means such as spreading propaganda, many in this period turned theoretically to terrorism as a means to achieve revolution and anarchist communism, or at least to weaken state and authority. State repression against publications and organizations such as the Socialist Party and the "Public Peace Policy Act," which effectively prevented the formation of trade unions , were two factors that fueled this trend. The only incident involved the arrest of four anarchists who had materials to make bombs. Although no attack was carried out and only four people were involved in the planning, 26 anarchists were convicted by a secret court on January 18, 1911, as members of a conspiracy to murder Emperor Meiji . Kōtoku was hanged on January 24, 1911 with ten others . The only woman Kōtokus mistress Kanno Suga was, the next day put to death , as it was dark. This incident came to be known as the treason affair - also known as the Kōtoku affair.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Frederick George grade assistant: Chapter 4: Pacifist opposition to the Russo-Japanese War, 1903-5 . In: Kōtoku Shūsui: Portrait of a Japanese Radical . Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1971, ISBN 978-0521079891 , pp. 106-107, OCLC 142930 , LCCN 76-134620 .

- ↑ The Anarchist Movement in Japan spunk.org

literature

- Maik Hendrik Sprotte : Conflicts in authoritarian systems of rule. A historical case study of the early socialist movement in Japan during the Meiji period . Marburg 2001, ISBN 3-8288-8323-0

Web links

- The Anarchist Movement in Japan , a script by John Crump

- e-texts of Kōtoku's work on Aozora Bunko (Japanese)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kōtoku, Shūsui |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 幸 徳 秋水 (Japanese); Kōtoku, Denjirō (real name); 幸 徳 傳 次郎 (Japanese, real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Japanese anarchist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 23, 1871 or November 5, 1871 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nakamura , Japan (today: Shimanto , Kōchi Prefecture , Japan ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 24, 1911 |