Arslan Hane

Arslan Hane or Arslanhane (dt. Lion House ) was a Byzantine church in Constantinople that was profaned during the time of the Ottoman Empire . The church was consecrated to Christ Chalkites ( Greek Χριστός τῆς Χαλκῆς ), whose image had been painted above the nearby Chalke gate since Justinian II . The gate, whose name probably derives from the doors or tiles made of bronze (Greek chálkeos ), was a reception building of the Great Palace of Constantinople. The upper floor of the secular church was badly damaged in a severe fire and demolished in 1804.

location

The building stood in the Sultanahmet district in the Istanbul district of Fatih, around 200 meters south of Hagia Sophia and not far from Justinian's Column and north of the Chalke Gate.

history

Byzantine Empire

According to the Patria Konstantinoupoleos , Emperor Romanos I had a chapel built in the 10th century, which was dedicated to "Christ Chalkites", the name of the image that was venerated at the entrance to the entrance hall of the Great Palace, the Chalke Gate. This image, one of the most important religious symbols of the city, played an important role in the Byzanintean icon controversy . The chapel was so small, however, that it could not accommodate more than fifteen people and was difficult to reach via a spiral staircase, which suggests that the chapel must have been on the upper floor of another building, possibly the Chalke itself. In 971, Emperor Johannes Tzimiskes expanded the chapel, built a two-story church to celebrate his victory against the Kievan Rus , and equipped the monastery with 50 clergymen. The new building, which was built partly from the material of the nearby, already dilapidated palace baths tou oikonomíou , was lavishly decorated. John I was buried in the church's crypt in 976. In 1183 Andronikos I was proclaimed co-emperor of the young Alexios II , who was killed immediately afterwards. According to a Russian pilgrim, the church was still in use in the second quarter of the fifteenth century.

Ottoman Empire

After Constantinople was conquered by the Ottomans in 1453, an artisanal barracks was built near the church and the church was abandoned. After that, the secular church, like the nearby church of St. Johannes am Dihippion , was used as a menagerie on the ground floor . The building housed wild animals such as lions, tigers, and elephants, which belonged to the nearby Topkapı Palace.

At the same time the windows on the upper floor were bricked up and the painters and Ottoman miniaturists working in the sultan's palace lived and worked here ( Turkish: Nakkaş hane ). In 1741 a fire in the area around Hagia Sophia damaged the building and the nearby Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamamı .

In 1802 the upper floor burned down and in 1804 the building was demolished. In the years that followed, there were a number of fires in the new buildings on the site, until the Swiss architect Gaspare Fossati built the headquarters of the new Istanbul University here between 1846 and 1848.

description

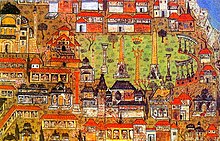

All that is known about the first chapel is that two marble columns used for its construction were brought from Thessaloniki . A depiction of the city in Schedel's world chronicle from 1493, another from 1532, painted by Matrakçı Nasuh , and an engraving in the geography book Géographie des quatre parties du monde , published in 1804 by the monastery of San Lazzaro degli Armeni in Venice, show the only three existing pictures of the church, although in the latter the building is already shown in ruins. It seems to have been built from ashlar and bricks and to have been designed as a central building with two floors, which was surmounted by a dome. The upper floor was flanked by two semi-domes and bordered by a terrace. Both floors were illuminated by windows. Inside, the church was adorned with precious vases and icons (such as the famous icon of Christ from Beirut ) and richly decorated with paintings and mosaics. The remains of this equipment as well as inscriptions in Greek were visible inside until the 18th century. Emperor Johannes Tzimiskes furnished the church with several relics, among them the alleged sandals of Jesus and hair of John the Baptist. His grave, adorned with gold and enamel, stood in the crypt or in front of the upper entrance.

literature

- Semavi Eyice: "Arslanhane" ve çevresinin arkeolojisi. Sur l'archéologie de l'édifice dit "Arslanhane" et de ses environs . In: İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri yıllığı , XI – XII, November 1964, pp. 23–33, 141–146

- Semavi Eyice: Arslanhane . In: Tekeli et al. (Ed.): Dünden Bugüne Istanbul Ansiklopedisi , Volume I, p. 325 f.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Raymond Janin : Les Églises et les Monastères . ( La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin , Part 1: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique , Volume 3), Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines, Paris 1953, p. 544

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wolfgang Müller-Wiener : Pictorial dictionary on the topography of Istanbul: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul up to the beginning of the 17th century . Wasmuth, Tübingen 1977, ISBN 978-3803010223 , p. 81

- ↑ a b Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger, Arne Effenberger: to church on a copper engraving by Gugas İnciciyan and the location of the Chalke Church . In: Byzantine Journal . Volume 97, Issue 1, pages 51-94, here p. 54

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Grèlois: Note sur la disparition de Saint-Jean au Dihippion . In: Revue des études byzantines . Volume 64, No. 64/65 (2006) p. 369–372 ( online )

- ↑ Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger, Arne Effenberger: To the church on an engraving by Gugas İnciciyan and to the location of the Chalke Church . In: Byzantine Journal . Volume 97, Issue 1, pages 51-94, here p. 81

- ^ Silvia Ronchey, Tommaso Braccini: Il romanzo di Costantinopoli. Guida letteraria alla Roma d'Oriente . Einaudi, Turin 2010, ISBN 978-88-06-18921-1 , p. 299

- ↑ Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger, Arne Effenberger: To the church on an engraving by Gugas İnciciyan and to the location of the Chalke Church . In: Byzantine Journal . Volume 97, Issue 1, pages 51-94, here p. 57 f.

- ^ Ernest Mamboury : The Tourists' Istanbul . Çituri Biraderler Basımevi, Istanbul 1953, p. 329

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller-Wiener : Picture dictionary on the topography of Istanbul: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul up to the beginning of the 17th century . Wasmuth, Tübingen 1977, ISBN 978-3803010223 , p. 329

- ^ A b Raymond Janin : Constantinople Byzantine . Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines, Paris 1964, p. 111

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller-Wiener : Picture dictionary on the topography of Istanbul: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul up to the beginning of the 17th century . Wasmuth, Tübingen 1977, ISBN 978-3803010223 , p. 71

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller-Wiener : Picture dictionary on the topography of Istanbul: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul up to the beginning of the 17th century . Wasmuth, Tübingen 1977, ISBN 978-3803010223 , p. 81

- ^ Adriano Balbi : Compendio di Geografia universale . Glauco Masi, Venice 1824, p. 4

- ↑ Alice Mary Talbot, Denis F. Sullivan: The History of Leo the Deacon . Washington 2005, p. 209