Except

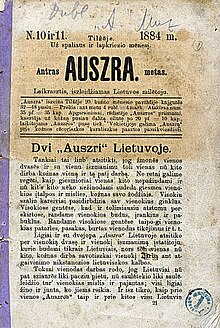

Aušra (also Auszra , English: Dawn ) was the first Lithuanian people's newspaper. The first edition appeared in 1883 in Ragnit , in Russian Neman , in Lithuania Minor . It was later published monthly in Tilsit , now Sovietsk . Although only 40 issues appeared and the circulation did not exceed 1000 copies, this publication is regarded by many scholars as an important event for Lithuania and as the beginning of the national revival that ultimately resulted in Lithuania's independence after the end of the First World War . The time between the first appearance of Aušra in 1883 and the lifting of the publication ban in 1904 is also called Aušros gadynė (time of dawn) in Lithuania .

history

After the Russian authorities refused permission to publish a Lithuanian newspaper in Vilnius , Jonas Šliūpas suggested that it be published in East Prussia . However, he himself was considered too radical for the task, and the printer Jurgis Mikšas asked Jonas Basanavičius to be the first editor. During its three-year publication, Aušra had no fewer than five editors. When Mikšas had to take a break for personal reasons, Šliūpas was entrusted with the printing process. However , there was a quick dispute between him and Basanavičius, who lived in Bulgaria , which was ignited by Šliūpa's unsolicited and insulting comments on the articles of other authors. Šliūpas also had difficulties with the German police because of his involvement in nationalist movements and had to leave Prussia in 1894. The other editors, Martynas Jankus and Jonas Andziulaitis, held back with polemical texts, and the disputes calmed down. However, Mikšas soon got into debt and could no longer support the newspaper. In 1886 the newspaper had to stop publishing.

The newspaper appeared outside of Lithuania. The authorities of the Russian Empire put a publication ban in force after the January uprising in 1863. It was forbidden to publish any literature in the Lithuanian language and using the Latin alphabet ; the government wanted to enforce the Grahdanka, a Lithuanian written in Cyrillic letters . That is why printing with Latin letters was relocated abroad, mainly to Lithuania Minor, and Knygnešiai ( book bearers ) smuggled the printing works across the German-Russian border. This was one of the ways in which Aušra reached her readers; it was also sent in sealed envelopes.

content

More than 70 people contributed to Aušra . The authors, also known as Aušrininkai , came from wealthy farming families, who gained importance after the abolition of serfdom in 1863. Many of the authors had trained at Russian universities and were fluent in Polish. Because of the frequent changes in the editorial team, the newspaper did not have a clear and consistent orientation. Basanavičius, for example, did not see Aušra as a political publication; in the first edition he announced that it would deal exclusively with cultural topics. Soon, however, the newspaper took a nationalist stand. Aušra helped crystallize many ideas about the Lithuanian people and their self-view. Plans to restore the Polish-Lithuanian Union have been rejected. The authors began to think about an independent Lithuanian nation-state.

Aušra published many articles on a variety of subjects such as agriculture or reports from Lithuanian communities in the United States , but the most popular were history subjects . The foreword of the first edition was introduced with a Latin saying: Homines historiarum ignari semper sunt pueri ( Whoever ignores history remains a child forever ). The history articles were based on the works of Simonas Daukantas , the first Lithuanian historian, and painted a glorified picture of the mighty Lithuanian Grand Duchy . Aušra maintained an anti-Polish position, especially one directed against the Polish nobility, but tried to avoid confrontation with Tsarist Russia in the hope of lifting the ban on the press.

The newspaper was aimed at the intellectual upper class and therefore had only a limited readership. The common people in the country did not approve of the secular orientation of the Aušra and their distance from Catholic traditions.

Follow-up publications

Soon after Aušra ceased publication, new magazines appeared in Lithuanian: Varpas ( The Bell ) was a secular newspaper, while Šviesa was more conservative and clergy.

literature

- Virgil Krapauskas: The Historiography of Auszra and the Aušrininkai. In: The Case of Nineteenth-Century Lithuanian Historicism . Columbia University Press, New York 2000, ISBN 0-88033-457-6 , pp. 107-118

- Except . In: Encyclopedia Lituanica , Volume 1. Boston MA 1970-1978