Baghdad battery

The Baghdad Battery , also known as the Battery of the Parthians or Battery of Khu-jut Rabuah , is a clay vessel that was found in 1936 during excavations of a Parthian settlement on the site of the Khujut Rabuah hill near Baghdad . The painter Wilhelm König , who was just visiting Iraq, speculated that, since it contains a copper cylinder and an iron rod, it - connected in a row with similar objects - could have served as a battery 2000 years ago , and actually still as electricity according to current knowledge was unknown.

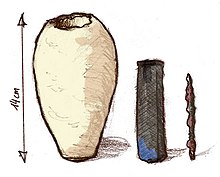

The container

The Baghdad battery is a vase-shaped clay vessel about 14 centimeters high, the largest diameter of which is around 8 centimeters. It contains a closed, approximately 9 centimeter long copper cylinder with a diameter of 26 millimeters. In this was held by a kind of plug made of asphalt (bitumen mass), a strongly oxidized iron rod. Its upper end protruded about 1 centimeter above the stopper and was covered by a yellow-gray oxidation layer. There is no conductive contact between the two metals.

In 1978 the vessel was shown in Geneva and then in the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim with the name "Apparat" and described in the catalog. The Hildesheim presentation in particular led to a flood of conjectures about the object, now known as the Parthian Battery , of which none have yet been verified.

Whereabouts

Shortly after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Iraqi National Museum , which housed the Baghdad battery, was ransacked. She has since disappeared.

Finds

In 1936 only one object was found with exactly this arrangement of the two metals. It was found on the hill of Khujut Rabuah near Baghdad, as part of the uncovering of a historical Parthian settlement from 250 BC. Chr. To 225 AD. The first traces of the settlement were discovered by chance through heavy rain.

Wilhelm König, who worked for the Iraqi National Museum in Baghdad at the time , documented this clay container found under a building outside the town center. Similar vessels, which can be distinguished mainly according to their content, had already been found and examined in more detail:

- Under the archaeological direction of Leroy Waterman , University of Michigan , four locked clay pots were excavated near Seleukia in 1930 . Three of these finds, dated to the late Sassanid period (5th to 6th centuries AD), were sealed with bitumen. These vessels contained a bronze cylinder, sealed again, in which was a pressed papyrus wrap. Although no characters could be detected on any of these largely disintegrated fiber rolls, but on the other hand these clay containers were staked with up to four metal rods made of bronze and iron sunk into the ground, it is concluded that they were ritual and used. The fourth vessel, also sealed, contained broken glass.

- A German-American excavation expedition led by Ernst Kühnel found six further clay vessels in the immediately adjacent ctesiphon , including three sealed objects with one, three and ten wrapped and sealed bronze rolls each. Within these bronze wraps there were already severely decomposed cellulose fibers. Another clay vessel contained three sealed bronze cylinders. In the other two vessels, which were also sealed, there were platelets made of originally pure lead, coated with lead carbonate; in the other ten heavily corroded iron nails, on which traces of a wrapped organic fiber material could be detected. Although a round roll of metal foil and paper is reminiscent of the typical design feature of a z. B. built up with soaked paper electrolytic capacitor , but there is no directly tangible electrophysical functional basis for this as well as the finds unearthed at Seleukia due to the obviously missing counter electrode.

Wilhelm König has been of the opinion since 1938 that the clay container without handles found in Khujut Rabua can only be a galvanic element or a battery. A number of controversial treatises refer to this point of view to date.

Batteries hypothesis

Wilhelm König's information on the structure and suitability of the Parthian battery as a galvanic cell was confirmed in 1962 by Walter Winton, historian at the Science Museum London. At that time Winton had reorganized the Iraqi National Museum and examined an exhibit there. Accordingly, the type of find described by König is a closed arrangement, fixed and sealed with a bitumen-like mass, which is perceived by several scientific as well as media-popular contributions as the electrode unit of a battery. If one follows their interpretation as the main component of a galvanic cell, the closed structure described by König was able to protect a partially filled electrolyte (including citric acid or diluted acetic acid) from drying out as well as contamination even under unfavorable ambient conditions.

As can be deduced from the electrochemical voltage series of the elements , there is a potential difference of at most approx. 0.79 volts for copper and also pure iron as a galvanic electrode pair. However, a cell voltage that is generally dependent on the electrolytic properties and therefore also lower, cannot be represented for the specimen recorded by König and other find variants, because a reliable conclusion about any reaction carrier worked into their metal surfaces is not available or possible.

Application hypotheses

The physicist George Gamow and the ancient historian Christopher Kelly ( University of Cambridge ) are among the scientists who refer to the electrochemical metal refinement favored by Wilhelm König . The antiquity researcher Paul Craddock, who works for the British Museum , points out, however, that there are no records or findings that can be clearly interpreted to prove such a procedure practiced in the Parthian Empire . Nevertheless leads Craddock, who worked as an expert for metallurgical Fund analyzes the Middle East, with an applied in Parthian electrotherapy stimulation another hypothetical application example. König already postulated electrotherapeutic treatments, also without any substantiated historical knowledge. It remains to be seen whether the apparatus was used for the galvanic surface gold plating of silver coins.

Arne Eggebrecht , the director of the Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim , carried out an experiment in 1987 with a model of the Baghdad battery. A voltage of 0.5 volts could be generated, which was sufficient to carry out subsequent electroplating.

In 1985, Emmerich Paszthory came to the conclusion that the copper cylinder finds were more likely to be protective containers for papyri with cursing and incantation formulas than power sources. The current flow is low when the vessel is closed, since no oxygen as an oxidizing agent can maintain the redox reaction. The magical metals copper and iron, as well as the organic remains in the vessels, which were found by other expeditions, suggest a rather mystical occult meaning of the vessels.

literature

- Wilhelm König: A galvanic element from the Parthian era? In: Research and Progress , 1938, 14, pp. 8–9.

- G. Dubpernell: Evidence of the use of primitive batteries in antiquity . Selected Topics in the History of Electrochemistry. The Electrochemical Society, I-22, Princeton NJ, 1978.

- G. Eggert: The Enigma of the 'Battery of Baghdad' . Proceedings 7th European Skeptics Conference. 1995.

- G. Eggert: On the Origin of a Gliding Method of the Baghdad Silversmiths . In: Gold Bulletin, 1995, 28 (1); link.springer.com (PDF).

- G. Eggert: The enigmatic “battery of Baghdad” . In: Skeptical Inquirer , May-June 1996 V20 N3 PG31 (4).

- JC MacKechnie: An Early Electric cell? In: Journal of the Institute of Electrical Engineers , 6, 1960, pp. 356-357.

- Markus Pössel: Fantastic Science. About Erich von Däniken and Johannes von Buttlar . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-499-60259-8 , p. 17th ff .

- Wilhelm König: Nine Years of Iraq . Rudolf M. Rohrer, Brno / Munich / Vienna 1940, p. 165 ff .

- Karin Adhal (ed.): Sumer Assur Babylon, 7000 years of art and culture between the Euphrates and Tigris. von Zabern, Mainz 1978, ISBN 3-8053-0350-5 (= Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum, June 23 - September 24, 1978, exhibition catalog, cat. no. 182).

- Gottfried Kirchner (Ed.): Reports from the Old World. New methods and findings in archeology. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-596-23511-1 , pp. 99-103.

Web links

- Replica of the Baghdad battery. (No longer available online.) Technisches Museum Wien , archived from the original on March 4, 2016 .

- Frank Dörnenburg: The light of the pharaohs - energy sources

- Walter Hain: Electricity in Antiquity? Did the Parthians have electric batteries, the Egyptians incandescent lamps, and the Maya electric motors? (via the Baghdad Battery and Dendera Relief )

- Parthian Battery (Iran Chamber Society, English)

- Graphic of the Baghdad battery on Ampère et l'histoire de l'électricité (French)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Wilhelm König (1938): A galvanic element from the Parthian era? In: Research and Progress , 14: 8–9 .; Walter Winton: Baghdad Batteries BC In: SUMER. Vol. XVIII, 1962, p. 87.

- ^ A. Al-Haik: The Rabbou'a Galvanic Cell. In: SUMER. Vol. XX, 1964, pp. 103-104.

- ↑ Shivani Yadav: The Curious Disappearance of the Baghdad Battery: A Parthian Period Relic, An Oopart . In: STSTW Media - Stories That Shocked the World, January 11, 2019, accessed on March 16, 2019 (English); ICSSI Baghdad: Who Stole the Mysterious Baghdad Battery? , 2016-01-12, (iraqicivilsociety.org, accessed 2019-03-16).

- ^ Leroy Waterman: Preliminary Report upon the Excavations at Tel Umar, Iraq. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1931.

- ^ From the earliest publications by JM Upton: The Expedition to Ctesiphon, 1931–1932. In: Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 27, pp. 188-197; Emmerich Paszthory: power generation or magic. In: Ancient World. 16, 1985.

- ^ Ernst Kühnel: The results of the second Ctesiphon expedition. In: Researches and Advances. No. 8, 1932; Ernst Kühnel: The excavations of the second Ctesiphon expedition. ed. Islamic Art Department of the State Museums in Berlin. 1933.

- ↑ To the synoptic overview u. a. Nasser Kanani: The Parthian Battery - Electric Current 2,000 Years Ago? Eugen G. Leuze Verlag, Saulgau 2004.

- ^ Walter Winton: Baghdad Batteries BC In: SUMER. Vol. XVIII, 1962 edition, pp. 87-88. (English)

- ^ Nasser Kanani: The Parthian Battery: Electric Current 2,000 Years Ago? ( Memento from April 1, 2010 on the Internet Archive ) In: Gahname - VINI trade journal. No. 7, 2004, list of sources pp. 201–203. Crackling sparks . In: Der Spiegel . No. 40 , 1978 ( online ).

-

↑ George Gamow: Birth and Death of the Sun. Verlag Birkhäuser, Basel 1947.

Kelly's lecture with Ali McGrath, Stuart Clarke: Ancient Inventions. Ancient Discoveries DVD and TV film series . Title of the German version: Hightech der Antike. Inventions between the Tiber and the Tigris. TV report (ZDF and Phoenix). - ↑ BBC News: Riddle of 'Baghdad's batteries' , February 27, 2004, accessed March 16, 2019.

- ^ Wilhelm König: Nine Years of Iraq . Rudolf M. Rohrer, Brno / Munich / Vienna 1940, p. 155-184 .

- ↑ Roland M. Horn: Mankind riddle : From Atlantis to Sirius , ISBN 978-3-7418-3767-8 ( partial preview online )

- ↑ Emmerich Paszthory: Power generation or magic. The analysis of an unusual group of finds from Mesopotamia . Ed .: E. Paszthory. Ancient World, 1985, p. 3-12 .