Illustration of the traffic signs in the German Reich from 1910 to 1923

The illustration of the traffic signs in the German Reich from 1910 to 1923 shows the traffic signs in the German Empire during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic , as laid down in the International Agreement on Motor Vehicle Traffic of October 11, 1909 . The conference held in Paris at the time brought about the first significant union of states that reacted to the internationalizing automobile traffic with unified standards.

The member states undertook to ensure that dangerous road spots are secured with the warning signs prescribed by the conference. Deviations from these signs were only possible through mutual questioning of the member states. The contract emphasized that, in particular, signs for customs offices, toll booths and tax levers are freely permitted. The ratification took place on March 1st, 1910. The automobile clubs and associations were to take care of the list.

The symbols decided on at the time were groundbreaking and some of them are still in use today. The symbol for curve was only replaced by a new graphic in West Germany from 1971 and the symbol for level crossing was not removed from the road traffic regulations until 2013.

Officially prescribed boards

Warning signs in accordance with Annex D to Section 8 of the International Transport Agreement of 1909

International warning signs

Other state-decreed boards

With the first amendment to the Automobile Traffic Ordinance on February 3, 1910, three new boards measuring 0.50 × 0.50 meters were introduced throughout the Reich: motor vehicles 15 km , ban on motor vehicles and motorcycles , ban on motor vehicles, open to motorcycles . In 1910 it was regulated by law that motor vehicles no longer had to reduce their driving speed to less than 15 km / h within built-up areas. Local police authorities were only able to prescribe lower inner-city speeds for vehicles over 5.5 tons. The blue and yellow tones and the typography of the characters were not standardized and sometimes differed significantly from one another. The texts on the boards could also be designed differently despite official requirements.

Panels added later

On the basis of the tablets prescribed in the novella of 1910, the following symbols appeared shortly afterwards. In 1919 it was determined that rubber-tyred trucks with internal combustion engines should not exceed a maximum speed of 15 to 16 km / h. For trucks as towing vehicles , 12 to 14 km / h were to be aimed for. For rubber-tyred trucks with electric drive , practice in the same year had shown that a top speed of 18 km / h was realistic. The truck speed limit shown below was a locally used variant of the official black and blue speed signs.

Other tables, some of which are regionally distributed

Many early road signs were put up on private or commercial initiative. So in 1912 the ADAC and in this phase also the AvD began to set up place-name signs and signposts. The companies Dunlop and the Continental-Caoutchouc- and Gutta-Percha Compagnie were won over to participate in the financing of these signs . Continental's signposts consisted of two-part boards that were attached to house walls around five meters above street level, either side by side or one below the other. Each of the panels was about half a meter high and about a meter wide. The actual signpost was red in color. The letters with the destination and the arrow underneath were white. The border of the signpost was made in yellow. The second board that went with it was intended as a direct advertisement for Continental. It was labeled the company and was blue and white. In addition to these clubs that are active throughout Germany, regional connections such as the Bavarian Automobile Club also set up warning signs.

Many areas, including traffic safety as well as environmental and health pollution, which are now regulated by appropriate signs, were topics in Reichstag sessions even before the First World War . In March 1912, for example, the central politician Michael Krings made an inquiry about the harmful dust nuisance caused by rail and car traffic. The then director of the Reich Office of the Interior, Theodor Lewald, replied to the question that the main cause was the poor German road conditions and that an improvement could be achieved through construction work. He also wants to initiate a discussion at one of the next international transport congresses in order to discuss this topic. Lewald was convinced of the very positive results of tarred roads during a visit to England in September 1912: “That is something that is absolutely not known in Germany.” In February 1914 Lewald therefore referred to England that tarred roads the streets provide full remedy to the issue of dust development. An expert report on dust pollution, commissioned by the government in 1912 and prepared by the Imperial Biological Institute for Agriculture and Forestry , dealt with the issue of whether taring the country roads would cause direct damage to the adjacent natural and agricultural areas such as tree avenues and fields could cause. The results published in 1913 showed that no additional pollution from the tar dust for trees and agriculture would be expected. The beginning of the First World War prevented any further progress in road construction. Local police authorities responded to this issue by putting up speed limit signs by 1914.

Curbstones

In 1914, curbstones were described as follows: The rectangular workpieces are 1.20 meters high and have a square plan of 0.20 x 0.20 meters. The stones are to be painted white and their heads tarred black so that they remain visible in winter.

Warning signs for crossings

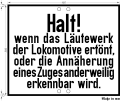

In Prussia and Hesse, three warning signs were required before the First World War, which the Prussian-Hessian Railway Association had to put up at crossings with and without barriers. The writing was to be executed sublime. These panels were retained in their original dimensions after 1918. After the establishment of the Deutsche Reichseisenbahnen on April 1, 1920, the tables became valid throughout the Reich.

literature

- Dietmar Fack: Automobiles, traffic and education. Motorization and socialization between acceleration and adaptation 1885–1945. Leske + Budrich, Opladen 2000, ISBN 3-81002386-8 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Federal Council Ordinance on the Use of Motor Vehicles of February 3, 1910 . In: Reichsgesetzblatt No. 5, 1910, p. 389 ff.

- ^ Ordinance on traffic with motor vehicles In: Reichsgesetzblatt 5, issued in Berlin on February 10, 1910, p. 389 ff.

- ↑ Weitz: The regulation on the traffic with motor vehicles of February 3, 1910 (Reichsgesetzblatt p. 389 ff.). Automobil-Rundschau des Mitteleuropean Motorwagen-Verein 5 (1910), p. 103 ff .; here: p. 110.

- ↑ The abolition of the rubber economy . In: Allgemeine Automobil-Zeitung 39, September 27, 1919, pp. 17-18; here: p. 18.

- ^ Electrical engineering and mechanical engineering 31, 37th year, 1919 p. 349.

- ↑ Freiherr von Löw: The driver's guide . In: Automobil-Rundschau. Journal of the Central European Motor Vehicle Association, issue 15/16, 1918, pp. 114–115: here: p. 115.

- ↑ Alfred Schau: The railway construction. Guide for teaching in the civil engineering departments of building trade schools and related technical schools . Teubner, Leipzig / Berlin 1914. p. 189.

- ↑ Ferdinand Loewe, Hermann Zimmermann (ed.): Handbuch der Ingenieurwissenschaften in five volumes , Vol. 4, Der Eisenbahnbau., Engelmann, Leipzig 1913, p. 85.

- ^ W. Cauer: Safety systems in the railway company . In: Reference library for civil engineers. Part 2, Railways and Urban Development, Vol. 7, Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 1922, p. 422.