Clave

The clave ( Spanish for “key”) is a rhythmic element in Latin American music , which is influenced by Africa , which is played on the claves , two round wooden sticks one to three centimeters in diameter and about 20 cm in length.

Types of clave

All variations of the clave are repetitive two-bar rhythm patterns that can be played in the form of 3-2 or 2-3 . 3-2 means that three beats are played in the first measure and two in the second measure, with 2-3 it is exactly the other way around.

Basically one can differentiate between the types of claves

- the underlying time signature, 4/4 or 6/8.

- according to whether the three beats falling in the first bar are equidistant from one another or whether the third beat has been shifted an eighth note back (and can thus also be heard as an early one of the second bar).

One differentiates u. a. the Son Clave , the Rumba Clave and the Bossa Nova Clave (although the terminology is inconsistent and ambiguous; the "Rumba Clave" as used below, for example, only exists in the most common form of Afro-Cuban rumba , the guaguancó ).

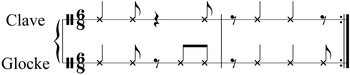

6/8 clave

The 6/8 clave is believed to be the original clave brought to Latin America by slaves from Africa, particularly those from Congo to Cuba. It is still used today in the music of various peoples in Africa as a bell figure and also as a concept. In Afro-Cuban folklore it is played in the ritual music of the Santería and in the rumba variant of Columbia . The bottom line is a common variant that is often heard as a 6/8 bell (in Cuban Columbia, parallel to the clave played on tonewoods). The similarity to the rumba clave is striking. It is assumed that the rumba clave originally developed from the 6/8 clave.

4/4 claves: son and rumba

The Rumba-Clave and the Son-Clave are played in 4/4 time. On them, d. H. mostly, but not always on the son-clave, a large part of Cuban popular music and Latin American music developed from it is based, e.g. B. Son (short for Son Cubano), Bolero , Salsa , Timba .

In the area of rumba, however, the terminology is a bit confusing; three different types of claves are used here:

- The Columbia is based on a 6/8 rhythm and accordingly uses the 6/8 clave.

- The Yambú can be notated in 4/4 time and uses the son clave.

- Only the Guaguancó (4/4) uses the so-called rumba clave.

This usage could be explained by the fact that the guaguancó is the most popular variant of the rumba.

A different linguistic usage describes each clave - whether 4/4 or 6/8, the third beat of which falls on the last eighth note before the second bar and can thus also be heard as the early one of the second bar - as a rumba or afro clave both the 6/8 clave and the 4/4 clave called the Rumba clave.

Like the 6/8 clave, the 4/4 clave also has five beats that are spread over two bars. If you play the first three beats in the first measure, it is called a 3-2 clave; by interchanging both measures one obtains the so-called 2-3-clave. Here first the Son-Clave:

The only difference between the Rumba-Clave and the Son-Clave is that the beat is shifted from the 4 to the 4+ in time.

Transition from 6/8 to 4/4 claves

In the 6/8 clave, the time interval between the 3rd and 4th beat is as long as the time interval between the 4th and 5th beat. This fundamentally distinguishes them from the 4/4 claves. Nevertheless, one perceives the 6/8 clave and the 4/4 clave as "the same" if the time signature in pieces of music changes immediately from 4/4 to 6/8 (and / or vice versa). This is a kind of "acoustic illusion".

Clave for odd meters

The Clave was further developed in the 90s. Especially representatives of the New York Latin jazz scene expanded the clave for odd meters. This is how the clave was created in 7/4 or 10/4 time. The most prominent representatives of this direction were Danilo Pérez (CD “Central Avenue”), David Sánchez (CD “Melaza”), Sebastian Schunke (CD “Symbiosis”), Antonio Sánchez and the bassist John Benitez .

Clave in Brazil

The traditional Afro-Brazilian musical styles like the music of the Candomblé are also structured by a clave, which is usually played on a cowbell called Gã or Gonguê . In the more modern popular Brazilian music, which also includes samba or samba reggae , there is no real clave. Instead, a linha rítmica (guideline) such as the Partido Alto or the so-called "Bossa-Clave" is played by the agogôs or accented by the caixas or repiques in samba . The main difference to a clave is that the linha rítmica is played around in a variety of ways .

Clave in pop music

The 3-2 clave in particular also runs through a large part of western pop music. It often appears as an accompanying pattern - whether only hinted at or clearly played out, as in the Bo Diddley Beat played on the guitar (something like the signature rhythm of rock'n'roll pioneer Bo Diddley ). Examples of the latter are the Bo Diddley composition Mona, recorded by the Rolling Stones , or George Michael's piece Faith .

meaning

According to the literal translation, the clave can be seen as the key to Latin American music. It is not just a rhythmic structure, but rather represents a complex and fundamental concept, especially in the African music of Latin America. The two-bar clave pattern is decisive. The 3-way side of the clave builds up tension, which is released again on the 2-way side. This tension determines the arrangement of the entire piece. All intros, outros and breaks (cierres) as well as melodies and accompaniment patterns and the musicians themselves are based on the “direction” of the clave. The clave usually runs through the whole piece and does not change in the process. The interesting thing is that the actual clave pattern often doesn't have to be played. It pulsates with the music, can be heard from the percussion rhythms as well as from the montunos that are played by the piano . Experienced musicians know intuitively which side of the clave they are currently on (2 or 3 side), so that they never lose their rhythmic orientation with variations or improvisation. If a musician plays in the wrong or twisted clave, then one says he is playing “cruzado” ( Spanish for “over the cross”). This describes an effect that every musician can feel and check for himself when he plays the clave figure against each other with both hands. The secret lies in the 2nd beat of the 3-man figure and in the first beat of the 2-man figure. The 2nd beat of the 3-way figure is syncope , the first beat of the 2-way figure is on the beat. At these two points the beats cross and trigger a braking effect that disrupts the rhythm (beat immediately followed by syncope or vice versa).

Apparent "turning" of the clave

Although the clave (and with it the entire rhythmic orientation, see above) usually goes through unchanged in a piece, the impression often arises that it would suddenly change within the piece, i.e. from 2-3 to 3-2, or vice versa. This occurs when the individual parts of the piece have odd bar numbers and so when changing to the next part, the perceived "beginning" of a musical unit is shifted compared to the clave.

The "classic" case of this "turning" of the clave takes place in the son at the transition from the "narrative" part to the call-and-response pattern between solo singer and choral singing (also called the Montuno part). Most of the time, one measure is "missing" in the last pass of the 4 (8, 16) "measure" pattern. The clave continues unchanged, with the effect that the rhythmic focus shifts to the "2" part. This shift makes the rhythm appear more driving. This effect is supported

- by switching to the already mentioned, repetitive call-and-response pattern,

- by the "acceleration" by the "missing" beat, often reinforced by an accentuation of the last two clave beats by the whole band or a prelude by an instrumental soloist (usually trumpet),

- by changing the bongo player to the bell (but usually only after the first call-and-response round),

- possibly by changing the timbales player (if available; timbales do not belong to the classic Son line-up; this is more relevant in salsa) from the cáscara to the louder, more aggressive-sounding timbales bell

- often by a gradual increase in speed

In this traditional structure, the transition takes place only once.

| "Twisted Clave" | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| part | Intro | verse | refrain | etc. | |||||||||||

| Tact | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4th | 5 | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14th | etc. |

| Clave | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | etc. |

In salsa, the traditional structure is partly replaced by the stanza-chorus pattern adopted from pop music, in this case the change between verse and chorus can take place several times in the piece. A piece can e.g. B. start in 3-2 and after 4 bars of the intro transition into the first verse, which is also played in 3-2. If this verse then has 5 bars, i.e. an odd number, the following chorus begins on the 2nd side of the clave, and the listener has the feeling that the clave has turned.

literature

- Ed Uribe: The Essence of Afro-Cuban Percussion and Drum Set. Warner Bros., Miami 1996