Compte rendu

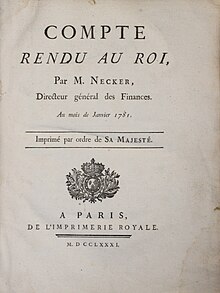

The Compte rendu (full name: Compte rendu au Roi ; German: Accountability report / financial report to the King ) is a document that was published on February 19, 1781 by the then French Finance Minister Jacques Necker . In it Necker gives an account of his previous reform policy and explains the current state of the royal state finances.

This compte rendu became famous because it was the first in the history of the Kingdom of France to publish figures on public finances. In addition, it gave rise to great discussions because it found a good surplus for the current year 1781. Many contemporaries and historians did not believe this excess because the France of the Ancien Régime had to contend with constant financial problems and, in 1781, had been participating in the American War of Independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain for three years .

Context: Necker's first ministry 1776–1781

On October 22, 1776, Jacques Necker was the first finance minister of France , initially with the title of Director General of the Royal Treasury ( Directeur général du trésor royal ), from June 29, 1777 as Director General of Finance ( Directeur général des finances ). Its most important task was to finance the American Revolutionary War , in which France actively intervened in 1778. To do this, he had to take out extensive loans and government bonds. In order to be able to bear the associated interest, he implemented numerous reforms and savings.

In order to be able to raise enough loans, Necker not only had to release sufficient funds to cover the interest costs, but he also had to be able to convince investors and financiers that their money was in safe hands with the French state. Over the course of the 18th century it had gone bankrupt several times (for example in 1715, 1721, 1726, 1759 and 1770) and the creditors of the state had to accept great losses each time. In addition, the monarchy's finances were state secret and had never been published, which also undermined its creditworthiness. Now Necker wanted to woo the creditors for trust and show that the finances of the state were healthy, even though it had been involved in an expensive war for several years. Therefore, with the consent of King Louis XVI. on February 19, 1781 his Compte rendu . It was the first time in French history that the public had seen figures on government finances.

content

The compte rendu contains an article in which Necker gives an account of his previous reform policy, and the actual financial report that follows with the figures for the year 1781.

Essay

The essay itself consists of a short foreword and three subsequent parts. The preface explains why the publication of public finances is advantageous. Ministers and other decision-makers in government need to know the state of finances so that they can shape their policies accordingly. In addition, the example of England shows that the state gets much more credit if it ends secrecy and plays with open cards. In England, the financial budget is presented annually to Parliament and then published and is therefore known at all times. Therefore England found much more credit, although it was smaller in population and area than France.

The first part sets out the state of finances and public credit. Here is the key part of the compte rendu , in which Necker assures that despite a structural deficit that still existed in 1776 and despite the large war expenditures, the state finances are healthy and there is now a good surplus of 10.2 million livres :

“Je me had dans ce moment d'annoncer à VM [Votre Majesté] que, tant par l'effet de mes soins et des diverse réformes qu'elle a permises, que par l'amélioration de ses revenus, ou par leur augmentation naturelle , et enfin par l'extinction de quelques rentes et de quelques remboursemens, l'état actuel de ses finances est tel que, malgré le déficit en 1776, malgré les dépenses immenses de la guerre, et malgré les intérêts des emprunts faits pour y subvenir , les revenus ordinaires de VM excèdent, dans ce moment, ses dépenses ordinaires de dix millions deux cent mille livres. »

"I now hasten to report to Your Majesty that, both as a result of my efforts and various reforms that you have allowed, as well as the increase in your income, or its natural increase, and finally through the cancellation of some pensions and school repayments The current state of your finances is such that, in spite of the deficit of 1776, in spite of the immense war expenses, and in spite of the interest on the bonds that were taken out for its maintenance, Your Majesty's ordinary income is currently your ordinary expenses of 10,200,000 Exceed Livre. "

In contrast to the last war ( Seven Years War ), in which the French state plunged into bankruptcy after three years of struggle (October 1759), the public credit remained stable this time. The French government finds enough money to finance its military involvement in the American War of Independence. Necker then turns to the anticipations (short-term advances) which, in his opinion, should not be too high because this type of loan only ran for a few months and therefore had to be renewed again and again, which could be difficult if the capital market dried up temporarily. Then the state bookkeeping ( comptabilité ) and the discount bank ( caisse d'escompte ) are briefly addressed.

The second part explains the various reforms within the financial management. First of all, pensions, bonuses and other pecuniary benefits are addressed ( dons, croupes et pensions ), an expense item that was an important debt factor in the ancien régime . Necker then describes how he limited the profits of the financiers, which must be seen in connection with the development of the state apparatus of the time. This was marked by a large deficit in bureaucracy. Through the institution of the sale of offices, important tasks and offices within the financial administration (tax collection, money management, billing, etc.) were sold to private entrepreneurs ( Ferme générale ), which, however, earned large sums for their services and made the management of the state cumbersome and complicated. Necker sought to reduce the profits of these private financiers and to control them better. The Compte rendu discusses the cashiers ( trésoriers ) , the main tax farmers for direct taxes ( Receveurs généraux ), the main tax farmers for the royal lands and forests ( Receveurs généraux des domaines et bois ), the payers of the royal pensions ( Payeurs des rentes de l'Hôtel de Ville ) and the great tax reform of 1780, which divided the collection of a large part of the indirect taxes between three large companies ( Division de la Perception de tous les droits entre trois compagnies ). Other issues addressed are the expenditure of the royal household ( Dépenses de la maison du roi ), which, according to Necker, have been greatly reduced, then the administration of the crown domains ( domaines du roi ) and royal forests ( forêts ) and the minting of coins ( monnaies ) . According to Necker, all of these reforms have not only led to major savings, but also to more order and clarity in the administration.

In the third, largest part of the essay, more general political issues and reforms come up, which, although not directly related to state finances, are nevertheless described as important for the general prosperity of the country (« dispositions générales, qui n'ont eu pour but que le plus grand bonheur de ses peuples et la prospérité de l'état »). Fiscal policy discussions take up a large part of this. The system of indirect taxes in France at that time was very complicated, unpredictable and also very unevenly distributed, which on the one hand meant constant uncertainty for taxpayers and on the other hand was detrimental to the economic climate in the country. Necker tried to make improvements here, but had to admit that some projects had to be postponed due to the war, especially those that caused a certain loss of earnings. Because in order to ensure the debt service he was anxious to the income of the king, Louis XVI. No matter how useful the associated reforms may not be belittled. So the reform of the capitation } (a kind of poll tax) had to be postponed, also that of the salt tax ( gabelles ). This was a particularly impressive example of how complicated the tax system was at the time. With regard to the salt tax, France was divided into several large main tax brackets, in which the salt price was very different. This range of prices led to large-scale salt smuggling, which in turn had to be fought using large resources. There were also great price differences within these main tax brackets, so that there was a permanent smuggling war practically throughout the country. In order to counteract this, Necker proposes two alternative measures in the Compte rendu : Either you abolish the salt tax completely, which is not possible in view of its large income of 54 million livres, or you at least ensure a fairly uniform salt price to prevent smuggling the basis will be withdrawn. But such complicated reforms could only be tackled after the war was over. Other issues raised by Necker tax types were the Twentieth on income ( vingtièmes ), the main income tax ( taille et capitation taillables ), the tax on official documents ( droits de contrôle ), border taxes and road tolls ( droits de traites et péages ), the local goods taxes ( aides ), taxes on office ownership ( centième denier , for the parties casuelle section ) and the fron ( corvée ).

In addition to these fiscal policy discussions, he also addresses issues of an institutional and socio-political nature. The provincial administrations in particular occupy a large area. This project, started by Necker, provided for the establishment of regional parliaments, which were supposed to seek solutions to regional political problems in the limited area of a province . In particular, the fair distribution of taxes, the handling of lawsuits from taxpayers, road maintenance and increasing general prosperity were among their central tasks. Although any decisions made by these administrations were tied to the royal approval and their full authority was not restricted, Necker recognized that it was neither necessary nor sensible if solutions were only ever based on Versailles . The people living in the region themselves often had much greater knowledge of local conditions and were therefore able to react to them much more precisely and sensitively than the distant royal government in Versailles.

Two further points concern the intendants des finances, which Necker abolished in 1777, as well as the Comité contentieux , a body for handling disputes and lawsuits, which is supposed to relieve the finance minister in his daily work. At the end of the essay, Necker deals with some economic and socio-political issues. One of these concerns the Mont-de-Piété ( Mont-de-piété et consignations ) , a state pawnshop that was supposed to allow young people who had moved to Paris from the provinces to take out small loans without paying the usurious interest often demanded by private lenders have to. In the following points about manufactures , weights and measures ( poids et mesures ) and the grain trade ( grains ) Necker speaks out in favor of a decidedly liberal economic policy. The factories should not be too regulated by the state, but the state should try to promote them and attract talented craftsmen from abroad. The various weights and measures should be standardized, but according to Necker this would be a huge job, because then many contracts and documents would have to be rewritten. The grain trade should in principle be free, but one should not go to extremes. In times of poor harvests it must also be possible to restrict it. Then the Maintmorte comes up , an old feudal law, which kept the serfs and their possessions under the control of the master. The king had exempted serfs from this right in his own lands, and Necker notes with satisfaction that several other liege lords had followed the royal example.

This is followed by explanations of the hospitals and prisons ( Hôpitaux et prisons ), which were often poorly organized and tended to worsen the condition of the patients or inmates. Necker and especially his wife, the Salonière Suzanne Necker , initiated some reforms here in the spirit of the Enlightenment . In 1778 Madame Necker had built a hospital in the Paris parish of Saint-Sulpice, which was organized according to modern medical principles and was to serve as a model for all other hospitals in the country. Necker then describes how he succeeded in building a new, larger prison, in which the inmates could be separated according to gender, age and type of offense.

In the end, Necker assures that he devoted himself to the important task that the king had given him with devotion and full commitment. He not only renounced private pleasure, but also served his friends with offices and gifts.

“Je ne sais si l'on trouvera que s'ai suivi la bonne route, mais certainement je l'ai cherchée, et ma vie entière, sans aucun mélange de distractions, a été consacrée à l'exercice des importantes fonctions que VM m 'a confiées; je n'ai sacrifié ni au crédit ni à la puissance, et j'ai dédaigné les jouissances de la vanité. J'ai renoncé même à la plus douce des satisfactions privées, celle de servir mes amis, ou d'obtenir la reconnoissance de ceux qui m'entourent. Si quelqu'un doit à ma simple faveur une pension, une place, un emploi, qu'on le nomme. »

“I do not know whether the path I have chosen will be considered the right one, but in any case I have looked for it, and my whole life, without any distraction, is devoted to the important tasks which Your Majesty has entrusted me with; I have sacrificed nothing for credit and nothing for the pleasures of life. I have renounced even the most beautiful of all private rewards, namely serving my friends or gaining recognition from those around me. If anyone owes a pension, an office, a job to my sole favor, they should be named. "

Financial report

The financial report presents the income and expenses of the royal treasury, which were expected to be incurred in 1781, as well as a list of the planned debt repayments.

First, there are two tables with a detailed listing of the income and expenditure which, according to the heading, flowed into the treasury for a “normal year” (“ portés aux trésor royal pour l'année ordinaire ”) or were made by them (“ payées au trésor royal pour l'année ordinaire »). The list for income includes 31 items and the list for expenses includes 49 items. All figures are rounded to the nearest 1000 livre and explanatory notes are added to some of the articles, such as: B. in Article 23 of Revenue, that the royal share of the revenues of the three largest tax leasing companies is likely to be greater than stated; or, in the case of Article 1 of the expenditure, that the pensions should from now on be paid centrally via the treasury and that the corresponding fund of the Navy has therefore been reduced by 8 million livres, etc.

The two detailed lists are followed by a short résumé in which the same numbers are repeated in the same order. Necker then draws the following conclusion:

| Total revenue | 264 154 000 |

| Total expenses | 253 954 000 |

| Revenue surplus | 10 200 000 |

Total income of 264 154,000 livre compared to total expenditure of 253,954,000 livre , which results in an income surplus of 10,200,000 livre . A final comment shows that this surplus is independent of the planned debt repayments of 17,326,666 livre , the list of which forms the end of the compte rendu .

Considering the purchasing power of a historical currency is difficult, here's an attempt: 1 Louis d'or was equivalent to 24 livres , 1 sou was one twentieth livre, 1 liard was equivalent to a quarter of a sou. An average table d'hôte or lunch menu was 1 livre; the price of a bread ranged from 2 sous to 12 sous. A cup of café au lait in a street café cost 2 sous. The usual seat in the Comédie française was available for 1 livre and in the Opéra for 2 livres, 8 sous. The trip by stagecoach, carrosse from Bordeaux to Paris cost 72 livres.

To interpret the numbers

The compte rendu and especially the financial report is not easy to understand. This is partly due to the fact that Necker himself does not provide any detailed information on the correct interpretation of his numbers in the compte rendu . Only his later works, which he published in connection with his controversy with Calonne ( Mémoire of April 1787 and the Nouveaux Éclaircissemens of August 1788), brought greater clarity.

Gross income vs. Net income

First of all, one has to say goodbye to the idea that we are dealing here with the entirety of the king's proper finances. While the compte rendu recorded ordinary income of 264 million livres, the total ordinary income of the king in 1781 was in fact around 430 million livres. The big difference stems from the fact that the compte rendu only records the finances that flowed into the royal treasury ( trésor royal ). Despite its name, this royal treasury was by no means a central treasury through which all state financial flows would have flowed. The weak bureaucratization of the financial administration at that time meant that there were many other coffers, which also administered the king's money and made state expenses. As a rule, only the remaining net income from these coffers (after deduction of all expenses to be paid by them) was transferred to the royal treasury, and it was these ordinary net income which are listed in the compte rendu . The ordinary gross income is not visible in the compte rendu and is only briefly mentioned by Necker in one place. However, they can be viewed at Mathon de la Cour, who published a collection of various financial reports in 1788 (including the Compte rendu of 1781). Accordingly, it amounted to approximately 427 million Livre and the prints ( deductions ) to about 163 million Livre , which then in the Compte rendu contained ordinary net income of 264 million gives Livre.

Ordinary vs. extraordinary finances

It is also important to note the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary income and expenses.

Ordinary income includes all taxes and duties levied annually on the people by royal authority (“ On doit entendre par les revenus ordinaires d'un état, ceux qui proviennent des contributions annuelles, levées sur les peuples en vertu des lois émanées de l'autorité souveraine. »)

Necker comments on the regular editions: “ Quant aux dépenses ordinaires, les unes sont fixées par des édits ou des declarations, telles que les rentes, soit perpétuelles, soit viagéres, les intérêts des effets au porteur, les gages des offices, etc .; les autres sont déterminées par des arrêts du conseil, et quelques-unes ont été simplement autorisées par des décisions particulières du souverain. »(German:“ As far as the ordinary expenses are concerned, some are fixed by edicts or declarations, such as permanent pensions and annuities, the interest of holders of notes, the fees for the offices, etc .; the others are fixed by council decisions, and others were simply authorized by individual decisions of the king. ")

Ordinary income and expenses could therefore come about in different ways, but the decisive factor was that they were all constant and fixed to a certain extent. Necker himself admitted that it would have led to less confusion if they had been named "fix" rather than "neat".

It was an undisputed accounting maxim at the time that proper expenses should be covered by proper income, which in the end means nothing other than striving for structurally balanced finances. Expenses for unforeseen and temporary expenses such as B. for wars or for dealing with natural disasters could and even had to be covered with loans, because they often far exceeded the amount of the regular budget. The decisive factor in this accounting concept was that the interest on the debt was included in the ordinary expenses in any case. Because as long as the debt service could be borne by proper income, there was no over-indebtedness. However, if the ordinary, fixed expenses and debt servicing could no longer be covered by the ordinary, annual income, then it was to be feared that the state would have to take out more and more loans and that the debt spiral would begin to turn uncontrollably. Based on these considerations, Neckers Compte rendu only took ordinary income and expenditure into account, because balanced, ordinary finances were considered a good indicator of healthy public finances. All extraordinary finances, especially the war costs or the borrowing, were therefore not to be found in the compte rendu .

It can be assumed that the headings of the income and expenditure lists in the Compte rendu ( pour l'année ordinaire ) are to be understood in the sense of an ordinary financial year. The opinion has sometimes been taken that Necker meant an average year by this année ordinaire , which he clearly denied.

Period calculation vs. Time calculation

Sometimes it has been mistakenly assumed that the compte rendu is a balance sheet in the sense of an annual financial statement. However, this is not possible because the report was published on February 19, 1781, when less than two months of the year had passed. It cannot therefore be of a retrospective (retrospective) nature, but only prospective (foresighted).

On the other hand, it is also imprecise to describe the compte rendu as a budget. A budget in our current sense of the word compares all income and expenditure for a certain person or corporation and for a certain period of time (usually a year), so it tries to map the entire budget period as precisely as possible. If, for example, a state decides on an annual budget, it is basically with the intention that the income and expenditure contained therein correspond to the actual year-end result. A budget is therefore a period calculation.

It is different with Compte rendu . This is not a period calculation, but a point in time calculation. It was only valid for January 1781 (when it was presented to the king) and partially for February 1781 (when it was published), after that no more, because the income and expenditure structure was constantly changing. In the same February and then in March, two new war loans were taken out, which increased the interest burden and thus made the compte rendu published on February 19 obsolete. So it was not a budget that planned the income and expenditure for the year 1781, but only the current income and expenditure status at the time of publication. He was a kind of fixed star, which indicated to the finance minister what the current financial situation of his country was and whether it could afford new loans or whether savings had to be made first. A compte rendu was only a time calculation, and after every new borrowing, after every new reform step, after every new change in the income and / or expenditure side, it was logically out of date and had to be replaced by a new one. Necker's figures from February 1781 were not intended to indicate that a decent surplus would actually be realized at the end of the year, but merely that there was currently a planned surplus in February 1781 that could be used to take out new loans.

Summary

In summary, Necker's Compte rendu is "a list of the ordinary net income and expenditure of the royal treasury. They form the currently (January 1781) valid income-expenditure plan for the year 1781."

Further Comptes rendus

Necker's Compte rendu is by no means the only one of the time. Other finance ministers have also prepared their own financial reports and submitted them to the king. The word “ compte rendu ” is therefore not specifically reserved for Necker's report of February 1781, but is simply the French word for accountability or financial report in general and also designates the reports of other finance ministers. Also worth mentioning are, for example:

- Compte rendu by Abbé Terray for 1774

- C. r. of Turgot for 1776

- C. r. by Bernard de Clugny for 1776

- Situation des finances by Joly de Fleury for 1783

- C. r. by Calonne for 1787

- C. r. by Loménie de Brienne for 1788

A collection of such Comptes rendus was published in 1788 by Mathon de la Cour (1738–1793). However, since Necker's report from 1781 is the best known, if there are no further additions, it is usually referred to as “ Compte rendu ”.

criticism

The compte rendu , especially the figures in the financial report, have been criticized by contemporaries and historians as incorrect.

Soon after the publication in February 1781 a pamphlet campaign was started, which questioned the correctness of the figures and in particular the established surplus of 10.2 million livres. Among them is one of the later Finance Minister Calonne with the title Les Comments ("The How's").

The controversy between Necker and Calonne 1787/1788

In November 1783, Alexandre de Calonne was appointed the new finance minister of France. Because he could not get the financial situation under control, he had to convene a meeting of notables for February 1787 . There he announced to the notables that Necker's Compte rendu had erred by at least 56 million livres and that the alleged surplus of 10.2 million livres was in fact a deficit of at least 46 million livres. Necker heard these remarks by the finance minister, and a journalistic feud developed between the two that lasted over a year and a half until the summer of 1788.

Necker first tried to get the king to have an opportunity to defend his numbers either publicly or in front of the notables. When he was denied this, he published a reply entitled Mémoire (German: memorandum) in April 1787, despite the royal ban . In it Necker goes into detail on the development of the state finances and rejects the figures presented by Calonne in front of the notables. During his first ministry from 1776 to 1781, according to Necker, he took out a total of around 530 million livres in loans for the state, which resulted in annual interest costs of around 45 million livres. In addition, according to the financial report of his predecessor Bernard de Clugny, there was still a decent deficit of 24 million in 1776 , which Neckers estimated at 27 million. But at the same time he also relieved the state accounts, both through increased income and reduced expenditure (which Necker subsumes under the keyword améliorations ). These reliefs, which Necker lists point by point in the Mémoire, would come to around 84 million livres annually - more than enough to cover both the additional annual interest of 45 million and the 24 million deficit of 1776 wear.

Necker then describes the further course that, in his opinion, the finances have taken from his resignation in 1781 to the present from 1787. According to Necker, it was in this epoch in which the financial sins occurred and the proper financial budget got out of hand.

Calonne responded to the Mémoire in January 1788 with his " Réponse de M. de Calonne à l'écrit de M. Necker " (German: "Answer from Monsieur de Calonne to the writing of Monsieur Necker"). Once again he affirms that in 1781 the actual financial course was different from the one claimed in Necker's Compte rendu . Calonne also gives many figures and goes through every single article in the compte rendu that he thinks was incorrect. The bottom line was that Necker had entered the income by 27 million livre too high and the expenditure by 29 million too low, which in total resulted in the deficit of 56 million livre he had put forward. With all these figures, Calonne refers to the so-called compte effectifs , which were probably a kind of year-end result of the income and expenditure actually realized. These are the only reliable documents when it comes to reconstructing the financial year. But they cannot be found and therefore remain mysterious. In the appendix to his response , Calonne presents 20 so-called pièces justificatives , which were a kind of confirmation letter and were intended to certify the authenticity of Calonne's figures, but they do not correspond to the comptes effectifs and their evidential value is therefore doubtful.

Necker responded to this letter from Calonne in August 1788, a few days before his renewed appointment to the head of the Ministry of Finance, with the letter " Nouveaux Éclaircissemens sur le compte rendu au roi " (German: "Repeated explanations on the king's accountability report"). This pamphlet is quite extensive, and Necker goes through all of Calonne's allegations point by point. In one chapter he frankly admits that at the end of the year not all of the figures were realized as assumed in the compte rendu , but that this is inevitable in a prospective report. Besides, the shortfall does not speak in favor of Calonne, but in favor of his own, because the ascertained surplus is even higher than assumed in the compte rendu . In any case, Necker confirms once again that Calonne's allegations are completely untenable, that he constantly confuses ordinary and extraordinary finances and also disregards other accounting principles.

Then the controversy between Calonne and Necker ended. Calonne, who had been dismissed as finance minister during the meeting of notables in April 1787, fled to London soon afterwards because the Paris parliament had an arrest warrant against him on suspicion of disloyal management. After the publication of Necker's Nouveaux Éclaircissemens in the summer of 1788, Calonne announced another reply for the following year, but this never appeared.

The judgments of historians

Many historians have endorsed Calonnes' judgment and questioned the correctness of the compte rendu . This judgment seemed to be borne out by the fact that old France had almost constantly struggled with financial problems since the Middle Ages. In addition, it was particularly armed conflicts that put a strain on the state finances, and state bankruptcies often occurred during or at the end of a war (e.g. at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in the 1710s or in 1759 during the Seven Years' War). Hence the surplus recorded by Necker in his compte rendu seemed implausible. Numerous financial historians, especially of the 19th and early 20th centuries, have therefore described the compte rendu as misleading to completely wrong (a brief summary of this can be found in Harris in the Journal of Modern History .) René Stourm (1885), for example, said it had in France at that time there was no proper bookkeeping at all and therefore neither Necker's figures nor those of Calonne were unbelievable. Marcel Marion (1914) described the savings claimed by Necker as fictitious (" ces calculs fantaisistes ") and as half-measures and therefore there could not have been a proper surplus in 1781. But even more recent historians have mostly cut in the same direction. For example, in 1988 the economic historian Wolfgang Oppenheimer said in the only German-language Necker biography to date that Necker had glossed over his computer and presented it in a friendly light.

The American historian Robert D. Harris has contradicted this judgment. In 1979 and 1986 he published two books in which he dealt in detail with Necker's political career (“ Necker, Reform statesman of the Ancien Régime ” and “ Necker and the Revolution of 1789 ”). His point of view is that Necker's structural and institutional reforms have not been sufficiently appreciated by earlier financial historians and that the compte rendu should claim more credibility than Marion or Stourm allow it. In particular, he points to the point that both Calonne and later historians are barely able to cite credible documents or circumstantial evidence to support their figures, while Necker has archived credentials for all of his figures, most of which in his retirement home in Coppet, Switzerland (near Geneva) are still visible today. In addition, the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary finances is also quite sensible from an accounting point of view, and the fact that Necker did not include war expenses in his compte rendu was not a misleading, but general accounting practice at the time.

No historian has dealt in depth with the compte rendu since Harris and therefore the whole matter must be regarded as open from a scientific point of view.

swell

- Charles-Alexandre de Calonne: Réponse de M. de Calonne à l'écrit de M. Necker. London 1788.

- Charles-Joseph Mathon de la Cour: Collection de comptes-rendus, pièces authentiques, états et tableaux, concernant les finances de France, depuis 1758 jusqu'en 1787 . Lausanne 1788.

- Jacques Necker: Œuvres complètes. 15 volumes. Aalen 1970.

literature

- Françoise Bayard et al .: Dictionnaire des surintendants et contrôleurs généraux des finances du XVI e siècle à la Révolution française de 1789 , Paris 2000.

- Lucien Bély (ed.): Dictionnaire de l'Ancien Régime . Paris 2003.

- John Francis Bosher: French Finances 1770–1795, From Business to Bureaucracy . London 1970.

- Joel Felix, 'The problem with Necker's Compte-rendu au Roi (1781)'. In: Swann, J. and Felix, J. (eds.) The crisis of the absolute monarchy . Proceedings of the British Academy (184). British Academy / Oxford University Press, pp. 107-125.

- Robert D. Harris: Necker's Compte Rendu: A Reconsideration . In: The Journal of Modern History. Volume 42, No. 2 (June 1970), pp. 161-183.

- Robert D. Harris: French Finances and the American War, 1777-1783 . In: The Journal of Modern History. Volume 48, No. 2 (June 1976), pp. 233-258.

- Robert D. Harris: Necker, Reform Statesman of the Ancien Régime . London 1979.

- Marcel Marion: Histoire financière de la France , 6 volumes. Paris 1914.

- Wolfgang Oppenheimer: The king's banker . Munich 2006.

- René Stourm: Les finances de L'Ancien Régime et de la Révolution , 2 volumes. Paris 1885.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 2.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 2 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 12 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 23 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 26-28.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 35-39.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 43-46.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 49-51.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 51 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 52-58.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 58-61.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 61-66.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 66-71.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 71-74.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 34.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 6.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 92 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 109-118.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 82-86.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 86-91.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 107-109.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 118-121.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 121 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 122 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 93-96.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 96-107.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 81 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 78-81.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 124.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 125-129.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 129 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 130 f.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 132.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 133-138.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 138.

- ↑ Philip Nicholas Furbank: Diderot. A critical biography Secker & Warburg, London 1992, ISBN 0-436-16853-7 , p. 474.

- ^ Bosher: French finances , 67.

- ↑ Necker: Compte rendu. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 15.

- ^ Mathon de la Cour: Collection , 180.

- ↑ Necker: Nouveaux Éclaircissemens. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 271.

- ↑ Necker: Nouveaux Éclaircissemens. In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 272.

- ↑ Necker: Nouveaux Éclaircissemens . In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 269 f.

- ↑ Necker: Nouveaux Éclaircissemens . In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, p. 270 f.

- ^ Harris: Necker's Compte Rendu of 1781: A Reconsideration. In: The Journal of Modern History. Volume 42, No. 2, June 1970, p. 166.

- ↑ Harris: Necker and the Revolution of 1789. pp. 155-157.

- ^ Necker: Mémoire . In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 182-184.

- ^ Necker: Mémoire . In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 185-197.

- ↑ Calonne: Réponse , 26-60.

- ↑ Calonne: Réponse , 22.

- ^ Harris: Necker's Compte Rendu of 1781: A Reconsideration. In: The Journal of Modern History. Volume 42, No. 2, June 1970, pp. 173 f.

- ↑ Necker: Nouveaux Éclaircissemens . In: Œuvres complètes. Volume II, pp. 418-430.

- ^ Harris: Necker, Reform statesman of the Ancien Régime. 234.

- ^ Harris: Necker's Compte Rendu of 1781: A Reconsideration . In: The Journal of Modern History. Volume 42, No. 2, June 1970, pp. 161 f.

- ↑ Stourm: Les finances de l'Ancien Régime et de la Révolution. II, pp. 182-203.

- ^ Marion: Histoire financière. I, 321 FN 1.

- ^ Marion: Histoire financière , I, 294/326.

- ^ Oppenheimer: The king's banker. 142.

- ^ Robert D. Harris: Necker and the Revolution of 1789. University Press of America, 1986, ISBN 0-8191-5602-7 .

- ^ Harris: Necker, Reform statesman of the Ancien Régime. 220-222 / 229.

- ^ Harris: Necker, Reform statesman of the Ancien Régime. Pp. 222-225.