The cold light

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The cold light |

| Genus: | Drama in three acts |

| Original language: | German |

| Author: | Carl Zuckmayer |

| Premiere: | 3rd September 1955 |

| Place of premiere: | German theater |

| Place and time of the action: | 1939 to 1950 in Great Britain, the USA and on a British transport ship in the Atlantic |

| people | |

|

|

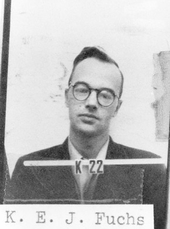

The cold light is a play by Carl Zuckmayer from 1955 about nuclear espionage. The plot is based on some data and facts on the case of the nuclear researcher Klaus Fuchs , who passed on important research results to the Soviet Union .

The first performance was on September 3, 1955 at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg (Director: Gustaf Gründgens )

content

The action takes place from 1939 to 1950 in Great Britain, the USA and on a British transport ship in the Atlantic. The play is divided into three acts and fourteen scenes.

first act

The first scene takes place in London's Green Park in September 1939: the young mathematician Kristof Wolters , who had to emigrate from Germany as a communist, is approached by Buschmann , a former comrade from the KPD . Buschmann tries to get Wolters, who has been granted a scholarship as a foreigner, as informants for the Soviet Union. At the beginning of the second scene, at the end of May 1940, Wolters and Buschmann find themselves after the outbreak of war as "deportation prisoners", ie enemy foreigners, on a British transport ship on their way to a Canadian camp. They share the cabin with Friedländer , an elderly, seriously ill Jew who has little chance of surviving the journey. The machines are shut down at night so as not to be a target for submarines. Wolters changes his mind and is recruited by Buschmann. The scene ends with an alarm and the request to put on the life jackets.

The third scene begins in London's Grosvenor House in the late summer of 1941. Wolters has returned after spending fifteen months in a camp and begins working in a secret laboratory for atomic research. His boss there is seventy-year-old Sir Elwin Ketterick . Here Wolters meets the young physicist Hjördis Lundburg from Norway again, with whom he was in love when he was first in London and who is now Ketterick's wife. Wolters owes his call to London to her advocacy. Fourth scene in Green Park, May 1943: Wolters, who is now a British citizen, meets with his contact Buschmann and gives them copies of his research and calculations. Both are about to leave: Buschmann to the Soviet Union, where he is supposed to be responsible for propaganda in a pioneer battalion, Wolters to the USA to a nuclear research facility.

Second act

The fifth scene takes place in Central Park West, New York City , in the middle of summer 1943 : Wolters is waiting for his new contact, Jurew. Before it even appears, however, he is approached by a local who describes himself as a bum (bum) and wants to make friends with him. After Jurew has come and has given the agreed secret signals for the second time, Wolters loses his nerve and falls away.

The sixth scene in the early summer of 1945 begins in a new building in Las Mesas, a nuclear city in New Mexico . Wolters is part of the British commission, whose task it is to check the results of the Manhattan District , where research is being carried out on the construction of the atomic bomb, and then to confirm them experimentally. Wolters met Hjördis again there. The head of the department is Nikolas Löwenschild , a man in his sixties. He informs Wolters that the bomb will probably be built soon, that it will only be about minor technical details. Wolters expresses his hope that it will no longer be used after Germany's defeat. Löwenschild assumes that Wolters has a guilty conscience about having participated in the development of the atomic bomb and wants to reassure him, but has the opposite effect: “What you do according to the law of your heart is not to blame. Only those who break trust are rejected. ”The seventh scene begins with a tennis game in Las Mesas on the evening of August 6, 1945. A party is announced for the later evening. Löwenschild asks Wolters to get some bottles of whiskey and smuggle them into the "atomic city", where alcohol is prohibited. This is convenient for Wolters, since he has a meeting with his contact, Jurew, in Santa Fe that same evening at half past seven . Before that, he gets closer to Hjördis, who is unhappy with Ketterick. This ends with the fact that she comes across a note in which Wolters carelessly noted the date and meeting point in Santa Fé. Wolters admits to having a meeting, but of course can't say with whom. Hjördis now knows that the whiskey purchase is a pretext and withdraws. Soon after, she has a discussion with Ketterick, during which she declares that she will stay with him. She hides the liaison with Wolters and the suspicious note.

Eighth scene, August 7th early in the morning: Wolters comes back much later than he would have needed for his errands and justifies this with a car breakdown. When an aircraft is heard, it is identified as a B-29 long-range bomber by a test pilot named Roy . Inspired by this, Ketterick and Löwenschild engage in a verbal exchange of blows about the atomic bomb: While Löwenschild feels scruples, Ketterick would like to throw it off immediately via Tokyo and Moscow . After Hjördis and Ketterick left the party, Angus Fillebrown , Kettering's assistant who has strong sympathy for the Soviet Union, a little drunk, raises the question of whether the technical creators of the bomb might not at least be obliged to counteract the military, or possibly even the Soviet Union to inform about these plans. Löwenschild describes such a breach of trust not only as inexcusable, but even as "wicked". Fillebrown then asks how one can still trust someone in this torn world. Löwenschild's assistant, the black Frederik Schiller Lee (a speaking name from Friedrich Schiller and the Southern General Robert Edward Lee ), makes a plea for diversity and the coexistence of irreconcilable opposites. Löwenschild concludes that a person's decency, or 'loyalty' as Schiller called it, is something one can believe in. Then there is dancing and singing. After almost everyone has left the room in a kind of polonaise, the radio program is interrupted and a speaker reads out the news of the atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima .

In the ninth scene in autumn 1945, Wolters meets his contact Jurew again in London's Green Park. He is dissatisfied because Wolters did not show up for the last three meetings. Wolters is of the opinion that he can no longer communicate anything essential and wants to end the meeting. He finally learns from Jurew that his first contact, Bushman, was convicted of being a traitor.

Third act

The tenth scene in December 1949 in the administration building of a state test and research station: the secret service officer Thomas Northon informs Sir Elwin Ketterick of the suspicion of espionage against Kristof Wolters. Although there are circumstantial evidence, unfortunately there is nothing suitable for a court such as testimony or evidence. At the moment the only option would be a voluntary confession. The as yet unsuspecting Wolters is summoned and Northon begins questioning. At the beginning of the eleventh scene on a January evening in 1950, Wolters and Northon enter a country inn about an hour's drive from London. An alleged attack on the car shortly beforehand turns out to be stupid: the landlord's son had shot cats. Northon is still trying to get Wolters to confess. In the end, Wolters leaves the inn and rushes off alone.

Twelfth scene: Early the next day, Ketterick telephones Northon and reports suspicious activity: Wolters spent hours organizing documents in his office, as if everything were to be handed over to a successor. An attempt to escape is conceivable. Northon replies that Wolters is on his way to see him. Afterwards, Ketterick confronts his wife about the affair she had with Wolters. In the course of a violent exchange of words, the old note with the meeting point in Santa-Fé falls into his hands. Hjördis had always carried it with him, but had never been able to interpret it properly. Together with the other evidence, this means proof for Ketterick that Wolters had actually met with a Soviet secret service agent. He informs Northon and, while still in the dark, goes to see him.

In the thirteenth scene, around the same time, Wolters arrives at Northon and tells him that he wants to end his work for the institute, since he has become a burden as a suspect. After a brief discussion, Northon informs him that Ketterick is on his way here with evidence: the note about the meeting in Santa Fé. Wolters thinks that Hjördis betrayed him and is desperate. Shortly afterwards the news arrives that Ketterick has had a fatal accident. Northon explains that Ketterick's wife didn't know what the note was about. Although the evidence has now been destroyed, Wolters decides to make a confession. In the fourteenth and last scene on a January afternoon, Northon meets Hjördis in Green Park and tells her about the essentials. He also brings her Wolters' affirmation that he always told her the truth about their relationship. Hjördis accepts this and asks Northon Wolters to say that she trusts him.

interpretation

In the afterword to the first book edition in 1955, Zuckmayer explains that the actual topic of the play is not the fission of the atom, but the crisis of confidence. There is a modern conflict of conscience, which in its dimensions is at most comparable to that during the wars of religion. Instead of the old metaphysical and religious motifs, however, doctrines claiming totality and the predominant role of science prevailed today. The latter two are able to confuse and superimpose the sense of honor and justice. This leads to actions the consequences of which are neither predictable nor controllable.

The inspiration is the case of nuclear researcher Klaus Fuchs from whom Zuckmayer took over a number of data and facts, such as the protagonist's origins from a pastor's family, left-wing extremist activities in youth and the escape from the National Socialists to Great Britain. Like Wolters, he completed a degree in mathematics there and was taken to a camp in Canada as an "enemy alien", from where he returned and did research on the theoretical development of the atomic bomb. He acquired British citizenship but continued to provide information to the Soviet Union's intelligence services. He continued this when he was called to the United States and after his return to Great Britain. The second character that goes back to a real-life model is investigator Thomas Northon. Zuckmayer was only aware of the official acts in this case and no further data. The psychology of these characters and their conversations are completely made up, as are the rest of the characters in the play.

Thomas Northon's conversations with Wolters are not of a criminalistic but of a philosophical nature and are similar to Wolters' conversations with Bushman. Northon and Buschmann embody opposing conceptions of freedom and conscience: For Buschmann, freedom is a principle and conscience is not an individual but a collective matter, while Northon emphasizes free will and the need for an individual examination of conscience.

On the title page of the book edition, "cold light" is explained as a term from nuclear physics that describes a luminous phenomenon that is not caused by heating or combustion. Tsebaya , a native Indian woman from New Mexico , tells Hjördis in the second act that the sexually mature female members of her people get up at the beginning of dusk, since the light at that time is still cold and evil and, if they are not careful, their fertility endanger. This is an allusion to radioactivity, whose “cold light”, in contrast to that of the sun, is hostile to life. Wolters confesses, after he decided to confess: "All my life I have stood in the beam of a cold light that came from outside and filled me with an inner frost." This "cold light" can be used as a symbol for Wolters' inner one There is a split: his political convictions allow him to provide information to the Soviet Union, while at the same time he feels like a traitor to the country that gives him work and protection.

The mentioned atomic city of Las Mesas in New Mexico probably means (La) Mesa , a table mountain with the research facilities of Los Alamos .

Productions

The cold light was not premiered by Heinz Hilpert , like the other important post-war dramas by Zuckmayer , but by Gustaf Gründgens.

- The first performance was on September 3, 1955 at the Hamburg Deutsches Schauspielhaus under the direction of Gustaf Gründgens.

- The cold light , a radio play directed by Gert Westphal, dates from 1955.

- The cold light , a television play by Südwestfunk, directed by Leo Mittler, set by Hermann Soherr, 1955

expenditure

- Carl Zuckmayer: The cold light. Drama in three acts . S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1955

- Carl Zuckmayer: The cold light. Plays . Frankfurt am Main, Fischer Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2003, 2nd edition ISBN 3-596-12711-4

Individual evidence

- ↑ Carl Zuckmayer: The cold light. Frankfurt am Main, Fischer Taschbuch-Verlag, 2003, 2nd edition ISBN 3-596-12711-4

- ^ A b Carl Zuckmayer: Epilogue to 'Kalten Licht' in: Das kalte Licht . Frankfurt am Main, Fischer Taschbuch-Verlag, 2003, 2nd edition ISBN 3-596-12711-4 pp. 241–244

- ↑ Clemens Özelt: Literature in the century of physics: history and function of interactive genres 1900-1975 . Wallstein Verlag 2018 Chapter: The Fall of a Man , p. 373

- ↑ Carl Zuckmayer: The cold light . Frankfurt am Main, Fischer Taschbuch-Verlag, 2003, 2nd edition ISBN 3-596-12711-4 title page

- ↑ Julia von Dall'Armi: Poetics of the split. Nuclear energy in German literature 1906–2011 , JB Metzler 2018, ISBN 978-3-658-21810-2 , p. 170. See also the passage in Das Kalte Licht , Fischer Taschenbuch 2003. Eighth scene p. 94

- ↑ Das kalte Licht , Fischer Taschenbuch 2003. 13 Szene p. 150

- ↑ Julia von Dall'Armi: Poetics of the split. Nuclear energy in German literature 1906–2011 , JB Metzler 2018. ISBN 978-3-658-21810-2 p. 172 ff.

- ↑ Julia von Dall'Armi: Poetics of the split. Nuclear energy in German literature 1906–2011 , JB Metzler 2018. ISBN 978-3-658-21810-2, footnote 271 on p. 168

- ↑ Wolf Gerhard Schmidt: Between Antimodern and Postmodern: The German Drama and Theater of the Post-War Era in an International Context , Chapter: The Diversification of the German Stage Landscape . ISBN 978-3-476-02309-4 p. 93

- ↑ The cold light - Fischer Taschenbuch 2003 (editorial note)

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk Kultur: The cold light . Entry for a broadcast on August 7, 2005, accessed on September 8, 2019

- ↑ krimiserien.heimat.eu: The cold light , accessed on September 8, 2019