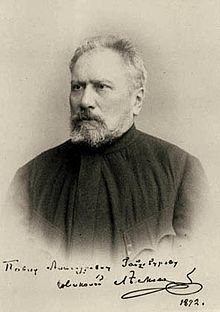

The clumsy (Nikolai Leskow)

The clumsy , also game with the phantom ( Russian Заячий ремиз , Sajatschi draw - Hasen remise ), is the last story by the Russian writer Nikolai Leskov , completed in 1894 and published posthumously in the Saint Petersburg magazine Niwa in September 1917 .

Edition history

This satire found no publisher in the tsarist empire of the 1890s. Vukol Lavrov of Russkaya Mysl wrote to Leskov: "It is absolutely impossible to print something like this these days ... The questions you raise will frenzy the censors, and you and we will get it." Mikhail Stasjulewitsch of Westnik Yevropy also refused.

Leskow then shelved this last manuscript.

content

The clumsy guy is the very strong, 60-year-old Onoprij Opanassowitsch Peregud. He had been a gendarme in his native Ukrainian village of Peregudy. He believed it was excessive love of fame that had brought him to a madhouse . No matter, he was recognized there as a lunatic and was knitting stockings for the other inmates.

His ancestor, Opanas, was a village elder and knight at the time of Catherine in Peregudy. The father, a nobleman, was Major a. D. The mother, also of noble origin, did not come from Peregudy.

The bishop, an old school friend of his father's, took Onoprij first as a choirboy and then as a novice. Inspector Vekovetschkin had taken the boy under his wing on behalf of the bishop.

When Onoprij is supposed to become a monk, he confesses to the bishop that he would rather get married. Onoprij fell in love with two at the same time; into the 14-year-old daughter of the lieutenant governor and into a very young, pretty maid.

Onoprij's father dies. As he had promised his father during his lifetime, the bishop used himself with the lieutenant governor for the apostate. Onoprij is registered as a state employee on the spot and from then on goes after horse thieves in Peregudy. He can't catch a thief. In his need he turns to Vekovetschkin. He hands him a booklet from the Moscow Synodal Printing House with the year 1864 and the title “Rules for illuminating the truth between two people who argue with one another”. Onoprij, following these instructions, scares the suspects with his talk so much that they finally confess. When Onoprij transferred all horse thieves to Peregudy according to the same recipe and neither the horse owner nor the superior authority thanked him, he wanted fame. Onoprij gets a hint from the governor himself about the new direction of work. The gendarme is supposed to report those who blaspheme, such as “Oh, how beautiful our life was when the ancestors didn't know how oppressive Moscow's yoke was.” Onoprij can use the “rules to illuminate the truth” when hunting to "shake", "make the thrones sway", do not help.

Onoprij leads the esteemed Julija Semyonovna on ice and writes a secret report. The staff officer cannot send the contents of the document to an address in a higher place because it is nothing more than quotations from the New Testament . In spite of all this, the officer praises the zeal, but it's not enough for a medal.

How now? Vekovechkin helps. The recipe for Onoprij: prescriptions are inappropriate. He has to act on his own. Onoprij researches his coachman Stetzko. And Stetzko should ask around; should listen carefully. The driver is soon fed up with the torture. Since he is neither a spy nor a rascal, Onoprij is supposed to drive his four-in-hand himself.

Onoprij all four horses are stolen. The injured party can be advised by Wekowetschkin about his upcoming appearance in court. The recommended motto: Talk puffy. This strategy angered the chairman increasingly.

Onoprij cannot find a coachman for his new horses. Out of necessity he takes a foreigner - Terenjka Naljotow from the Orjol governorate . When a leaflet appears in the Peregudy tavern with inadmissible sentences against the church, the nobility and the police, Onoprij promises the new coachman three rubles if he can teach the author of the pamphlet. It gets worse. Such a bad print product is found in the calash of the official Onoprij. It says "how ... the state collects taxes from morning to night".

Onoprij gets no rest. Now the district police chief is attacking him because he has caused unrest with the talk about the shockers. Onoprij continues anyway; accidentally arrests a government councilor while hunting down criminals.

During one of the next carriage rides, Terenjka Naljotow separates from Onoprij and disappears into the forest. Onoprij finds a bundle of leaflets from the criminal Terenjka under the seat. Onoprij wants to get rid of the leaflets, falls into a ravine with the whirling leaves and loses consciousness. Onoprij wakes up in the house of the aristocratic marshal and finds out that that councilor had hunted the criminal Terenika Nalyotov. The latter had been lured to Peregudy by Onoprij's talk of the shockers. The esteemed Julija Semyonovna mediates a conversation with the prince for Onoprij. He has Onoprij taken straight to the madhouse.

title

- Sajatschi draw - Hare draw means something like "senselessly chosen refuge of a hunted hare or madness as the last refuge of a failed person".

- According to Rudolf Marx, players speak of a draw when a straw man or a clumsy man is involved.

- See also: Sajatschi draw is a quarter of the city of Peterhof .

Self-testimony

- Leskow writes about his late work that the reader should be depressed and “... I don't want to please anymore. I want to scourge and torment it [the audience]. "

reception

- Müller-Kamp wrote in 1946 that Onoprij was "a simple, good person whom the authority mania of the autocratic state turns into a maniacal authority."

- Rudolf Marx wrote in 1972, “the little Ukrainian village nobleman” Onoprij hasche “in the era of the Pobedonoszews political opinion police ” according to an order.

- In 1973, Reissner wrote that Onoprij fell into his own trap while hunting down folk propagandists.

German-language editions

- Play with the phantom. Translated from Russian and provided with an afterword and notes by Erich Müller-Kamp . 125 pages. Herder library vol. 90, Freiburg im Breisgau 1961

- The clumsy. Observations, experiences and adventures of Onopri Peregud from Peregudy. German by Wilhelm Plackmeyer. P. 448–554 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The valley of tears. With a comment from the editor. 587 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1973 (1st edition)

Output used:

- Nikolaj Lesskow: The clumsy. Observations, experiences and adventures of Onoprij Peregud from Peregudy. Translation from Russian, epilogue and notes by Erich Müller-Kamp. 152 pages. Verlag Karl Alber , Munich 1946

Secondary literature

- Nikolai Leskov. His time and his life. From Rudolf Marx. P. 5–58 in Nikolai Leskow: The way out of the dark. Stories. 467 pages. Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1972 (Dieterich Collection, Vol. 142, 3rd edition)

Web links

- The text

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

- Entries in WorldCat

Remarks

- ↑ Viktor Golzew (Russian Гольцев, Виктор Александрович ), editor at Russkaya Mysl , was of the opinion of Vukol Lavrov. He had previously accused the author of a lack of harsh social criticism in the fairy tale Die Zeit nach Gottes Will , published in 1890 (Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 558, 20 Zvo).

- ↑ In this passage Leskov mocks the Russian judicial reform of 1864 (Eng. Judicial reform of Alexander II ): According to the new, more democratic law, the accused may no longer be accused of horse theft on the part of the injured Onoprij.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian Нива , The hallway

- ↑ Russian Лавров, Вукол Михайлович

- ↑ Russian Русская мысль (журнал)

- ↑ Russian Стасюлевич, Михаил Матвеевич

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 565, 10. Zvo

- ↑ Russian Перегуды

- ↑ Russian Вековечкин - Himmelsmann, Hammelmann (footnote edition used, p. 46), also: rare, unusual

- ↑ Edition used, p. 68, 4. Zvo

- ↑ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 566, 7th Zvu

- ↑ Rudolf Marx in 1972, p. 52, 10th Zvu

- ↑ Russian Заячий Ремиз

- ↑ Müller-Kamp quotes Leskow in the afterword of the edition used, p. 146

- ^ Müller-Kamp in the afterword of the edition used, p. 147

- ↑ Rudolf Marx in 1972, p. 52, 8th Zvu

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 566, 10. Zvo