Doomsday argument

The doomsday argument , German doomsday argument is a mathematical reasoning, which claimed a probability statement about the timing of the end of humanity to be able to meet on the basis of only an estimate of the total number of people been born.

It was first proposed by the astrophysicist Brandon Carter in the 1980s and subsequently advocated by the philosopher John Leslie . It was advanced independently by Richard Gott III and HB Nielsen . Similar theories that infer an end of the world from population statistics have been proposed earlier by Heinz von Foerster and others.

Formulation of the argument according to Richard Gott

Let us assume our position on the chronological list of all people who will ever be born, with the absolute position from the beginning of the list and the total number of people.

Assuming that we find ourselves in any position with equal probability (with other people) , we can deduce that our position follows a discrete uniform distribution on the interval before we find out our absolute position.

Let us also assume that our position is evenly distributed even when we experience our absolute position .

We can now say with a 95% probability that it is in the interval . In other words, we are 95% sure that we are in the last 95% of all people ever born.

Given our absolute position , that implies an upper bound for , by rearranging to .

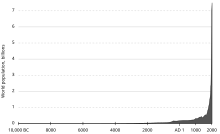

If we assume that up to now 60 billion people have been born (Leslie's assumption), then we can say with 95% probability that the total number of all people who will ever be born is below (billion).

From the assumptions that the world population will stabilize with 10 billion people living at the same time and that a life expectancy of 80 years will be reached, one can then calculate how long it will take until the remaining 1,140 billion people are born: with 95% probability it will survive humanity no more than another 9120 years. The result varies depending on the assumed future population development .

criticism

The validity of the doomsday argument is heavily disputed. At first sight, the Doomsday argument seems to be a simple calculation example, a mathematical calculation. However, it is overlooked that the calculation is based on a philosophical assumption, the so-called self-sampling assumption , which is extremely controversial. Since this is a philosophical assumption, like the entire Doomsday argument, it is controversially discussed not among mathematicians, but among philosophers.

The self-sampling assumption can be formulated as follows:

"Observers should reason as if they were a random sample from the set of all observers in their reference class."

"Observers should conclude as if they were a random sample from their reference class."

Even if one assumes this assumption to be valid, the question of the reference class still remains open: Take the class of all people who have ever lived (as in the calculation example above in the article), or at least the class of all living beings, all scientists, all People who were born in the year 2000 or later, etc. Depending on which class is used, the calculated probabilities change considerably.

The nature of the self-sampling assumption means that it can neither be proven nor refuted. However, numerous thought experiments have been constructed by critical researchers in which the application of the self-sampling assumption leads to intuitively implausible results.

Further remarks:

- A precise formulation of the argument requires a Bayesian interpretation of probability.

- The argument does not assume any prior knowledge of the distribution of . This is a reasonable assumption for reasoning in principle.

- The argument makes an implicit assumption that is limited. If one leaves physical arguments such as B. Aside the heat death of the universe, there could in principle be an infinite number of people. It is not clear how the argument would apply in this case.

- Even the correctness of the argument would not necessarily mean that humanity is extinct after 1,140 billion people have lived. There are other ways of interpretation, e.g. B. that humanity develops into posthuman beings through evolution (or specific self-development).

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Brandon Carter and William McCrea : The anthropic principle and its implications for biological evolution (= Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London . A310). 1983, p. 347-363 , doi : 10.1098 / rsta.1983.0096 .

- ↑ J. Richard Gott, III: Implications of the Copernican principle for our future prospects (= Nature . Volume 363 ). 1993, p. 315-319 , doi : 10.1038 / 363315a0 .

- ↑ Holger Bech Nielsen : Random dynamics and relations between the number of fermion generations and the fine structure constants (= Acta Physica Polonica . B20). 1989, p. 427-468 .

- ^ Paul Parsons: The Rough Guide to Surviving the End of the World . Rough Guides , 2012, pp. 6 ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Nick Bostrom , "The Doomsday Argument, Adam & Eve, UN ++, and Quantum Joe." Synthesis 127: 359-387, 2001 pdf file

- ↑ N. Bostrom: Anthropic Bias. Page 108 online

![{\ displaystyle (0; 1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/174351203b017beaeff8f72dd0848dbc594f3a62)

![{\ displaystyle (0.05; 1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/200dd2f3221acee3fa06717391cfa39984beaff7)