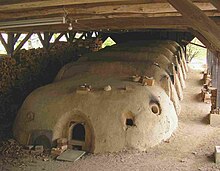

Dragon pottery furnace

A dragon pottery kiln , also called a climbing kiln , ( Chinese龍窯; Pinyin lóng yáo; Wade-Giles lung-yao) is a traditional Chinese form of pottery kiln for Chinese porcelain , especially in southern China. It is a long, narrow pottery kiln that is always built on a steep slope with a typically between 10 ° and 16 ° incline. The pottery kiln can reach very high temperatures, at times up to 1,400 ° C, which are required for high-fired ceramics, including stoneware and porcelain . This has long been a challenge for European potters. Some dragon pottery furnaces were very large and over sixty meters in length. This allowed you to burn over 25,000 pieces at the same time. Until the beginning of the 12th century , they could be over 135 m long. These pottery kilns could burn over 100,000 pieces.

history

According to recent excavations in the Shangyu District in northeast Zhejiang Province and elsewhere, the origins of the dragon pottery kiln can be traced back to the Shang Dynasty (around 1600-1046 BC) and coincide with the introduction of stoneware, where for the Burning 1,200 ° C and more were needed. These pottery kilns were much smaller than later examples, ranging from 5 to 12 meters in length, and the slope was less.

The dragon pottery furnace was further developed during the Warring States Period (from 475 to 221 BC) and the Wu Dynasty (from 200 to 280 AD). There were over 60 pottery kilns in Shangyu Province. The main design developed was then used in southern China until the Ming Dynasty . The pottery areas in southern China are mostly hilly, while those on the plains of northern China typically lack suitable slopes. Therefore the Mantou pottery kiln dominates there .

The Nanfeng Kiln in Guangdong Province is several centuries old and still working. The Shiwan and building ceramics were produced there. Today the Nanfeng kiln serves as a tourist attraction.

construction

The pottery kilns were usually built of bricks and are a type of moving flame kiln, where the flames move more or less horizontally, rather than up or down the floor. The firing time could be relatively short, that is, around 24 hours for a small pottery kiln. Earlier pottery kilns were ascending tunnels that were not divided into chambers. However, these pottery kilns had a staircase interval with a relatively flat floor level. Sometimes gravel or similar material was distributed on the floor so that the goods could be stacked vertically. From the Song Dynasty (from 1127 to 1279 AD), some pottery kilns were built as a series of chambers that gradually went up the slope. These had connecting doors to allow the pottery workers access during loading and unloading, but also for heating during the firing process. It could be up to 12 chambers. The chambered pottery kilns were normally used for the production of Longquan - Celadon pottery .

The main firebox was always at the bottom. There may also have been additional heating holes at intervals along the slope to allow additional fuel to be added and viewing holes to allow a view of the interior. There was usually a chimney at the top, but since a pottery kiln was built up the slope it didn't have to be big and could be left out entirely. The size and shape of the pottery kilns and chambers varied widely. The fire started at the bottom and moved up the slope. Wood or less often coal was used as fuel, which influenced the atmosphere of the burning process. Wood creates a reduced atmosphere, but coal creates an oxidizing atmosphere. The same mass of wood was always required to burn the same mass of pottery. Conventionally, Saggars - kiln furniture - used at least in the later periods. This enabled an innovation of the northern Ding pottery during the Song Dynasty.

The pottery kilns made it possible to burn large quantities of pottery at high temperatures, but the firing process was usually not constant over the entire length of the pottery kiln, which resulted in different quality and effects in the kilned pottery. Very often the high-chambered pottery furnaces produced better fired pottery because they heated up more slowly. An example of this is the wide range of colors in Chinese celadon ceramics, such as Yue and Longquan celadon ceramics, which can be explained by the fluctuations in the firing conditions. The variations in shades of white porcelain between and within the northern Ding ceramics and the southern Qingbai ceramics were also the result of the fuel used. Some of the most modern chamber furnaces were built to fire the Dehua porcelain , with precise control of the high temperatures being essential.

The dragon pottery furnace shape was imitated in Korea between 100 and 300 AD and much later in various types of anagama ovens in the Japanese Empire and elsewhere in East Asia . The huge quantities of Asian pottery produced were not unique. The large pottery kilns in the ancient Roman Empire , which had a completely different shape, could burn up to 40,000 pieces at the same time.

literature

- Clarence Eng: Colors and Contrast: Ceramic Traditions in Chinese Architecture, Brill, 2014, ISBN 978-9-0042-8528-6 .

- Rose Kerr, Joseph Needham and Nigel Wood: Science and Civilization in China : Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 12, Ceramic Technology , Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-521-83833-7 .

- Margaret Medley: The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, 3rd Edition, Phaidon, 1989, ISBN 0-7148-2593-X .

- Rawson, Jessica (ed.): The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2nd edition, British Museum Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7141-2446-9 .

- SJ Vainker: Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, British Museum Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-7141-1470-5 .

- Nigel Wood: Oxford Art Online , section "Dragon (long) kilns" in "China, §VIII, 2.2: Ceramics: Materials and techniques, Materials and techniques"

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d S. J. Vainker: Chinese Potter and Porcelain, 1991, p. 222

- ^ A b c Margaret Medley: The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, p. 14

- ^ A b Rose Kerr, Joseph Needham and Nigel Wood: Science and Civilization in China : Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 12, Ceramic Technology, 2004, p. 348.

- ^ Rose Kerr, Joseph Needham, and Nigel Wood: Science and Civilization in China : Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 12, Ceramic Technology, 2004, pp. 348-350.

- ↑ Vainker, SJ: Chinese Potter and Porcelain, 1991, p 50f.

- ↑ Rawson, Jessica: The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007, pp. 364f.

- ↑ Ancient Nanfeng Kiln , China Tour Advisors

- ^ Rawson, Jessica: The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007, p. 364.

- ^ A b Margaret: Medley: The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, pp. 147f.

- ↑ SJ Vainker: Chinese Potter and Porcelain, 1991, p 124th

- ^ Eng, Clarence: Colors and Contrast: Ceramic Traditions in Chinese Architecture, p. 18.

- ^ Margaret Medley: The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, p. 148.

- ↑ SJ Vainker: Chinese Potter and Porcelain, 1991, p 95th

- ↑ SJ Vainker: Chinese Potter and Porcelain, 1991, p 72nd

- ↑ SJ Vainker: Chinese Potter and Porcelain, 1991, p 95 and 124th

- Jump up ↑ Rose Kerr, Joseph Needham and Nigel Wood: Science and Civilization in China : Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 12, Ceramic Technology, 2004, pp. 350f.

- ↑ JP Hayes article from the Grove Dictionary of Art