1985 Mexico City earthquake

| 1985 Mexico City earthquake | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| date | September 19, 1985 | |

| Time | 13:17:50 UTC | |

| Magnitude | 8.0 M W | |

| depth | 21.18 km | |

| epicenter | 18 ° 32 ′ 18 ″ N , 102 ° 19 ′ 27 ″ W | |

| country | Mexico | |

| dead | more than 10,000 | |

The Mexico City earthquake (also known as the Michoacan earthquake ) on September 19, 1985 was the most devastating earthquake in Mexico's history, killing thousands . Tens of thousands were injured and a quarter of a million people were left homeless as a result of the destruction and damage to thousands of houses.

Geographical situation

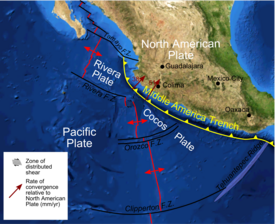

The epicenter was about 320 km west-southwest of Mexico City in the state of Michoacán . The region is close to the tectonic subduction zone of the Central America Trench , where the North American Plate and the Cocos Plate meet. Tensions had built up there since the two major earthquakes of 1911 (the Michoacán earthquake on June 7, 1911 and the Guerrero earthquake on December 16, 1911), which led to smaller earthquakes as early as the 1970s. On September 19, 1985 at 7:18 a.m. local time , these tensions erupted in a tremendous earthquake that lasted three minutes in the capital. The tremors could still be felt in Houston, 1200 km away . An aftershock almost as strong occurred on the evening of the following day a little further south-east. There were landslides , landslides , cracks in the ground and a tsunami with waves up to three meters high.

Damage and Consequences

Although much damage had occurred in the state of Jalisco , where more than 600 mud huts collapsed in the capital Ciudad Guzmán , the state capital Mexico City was hit hardest due to special geological factors. The city lies at the bottom of the dry Texcoco Lake and the loose sediments of the former body of water amplified the shock waves. More than 400 houses collapsed and thousands were damaged. The worst affected were 5 to 15-storey buildings, in which the vibration frequencies caused catastrophic resonance . Numerous buildings collapsed in the historic center, including the neoclassical Hotel Regis, churches, museums and hospitals. The economic damage has been estimated at three to four billion US dollars.

The failure of the electricity supply , the telephone network , traffic lights and public transport resulted in a chaotic situation. Although the power supply was restored the following day, it failed again due to the aftershock in the evening. There was a strong smell of gas in the air due to burst pipes and the authorities called on the radio to call on the population not to use matches.

President Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado's reaction to the disaster was later heavily criticized: for example, he would not have fully activated the national disaster control plan and would have hesitated too long before accepting foreign aid offers.

Relief measures were first led by local residents, who began to rescue people from the rubble and distribute aid. People from less badly affected neighborhoods helped in the badly affected neighborhoods in the center of the city, where more low-income social classes lived. These houses were built less robustly and accordingly many victims were lamented there. Care for the tens of thousands of injured was made difficult by the damage to many of the city's hospitals. Official sources spoke of 10,000 fatalities, but journalists and other eyewitnesses suspected much higher casualties. About 250,000 people were left homeless. The spontaneous self-help movement resulted in a political movement, the Coordinadora Única de Damnificados (CUD) . This successfully demanded from the president and the ruling PRI that the homeless should not simply be evacuated, but that new accommodation should be built for them. Two years later, 100,000 homes were restored or built with the help of World Bank funds . The CUD disbanded again in 1987 after their demands were met.

In the decades after the quake, the center of Mexico City blossomed into an attractive tourist destination, not least thanks to development projects by the Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim . The new and rebuilt buildings should be earthquake-proof and comply with building regulations. In the slums, which are now on the periphery and where hardly a tourist gets lost, things are different: The residents build where and how they can and have to fight for access to the most basic infrastructure such as water and electricity. It is feared that if there is another strong earthquake in these areas, many victims will be mourned.

The earthquake triggered the development of the world's first earthquake warning system , Sistema de Alerta Sísmica , which went into operation in August 1991.

Niños del sismo

The Juarez Hospital and the General Hospital were also among the collapsed buildings. During the rescue work - sometimes only days later - babies were rescued from the rubble. These children, known as bebés del milagro (miracle babies) or niños del sismo (children of the earthquake), were perceived or presented in the media as symbols of hope. Some of these children were found unharmed, others with serious injuries that also resulted in lifelong disabilities. Many had lost their parents and were raised by relatives. A team of doctors took care of her for years, and donations from home and abroad were made for her medical treatment.

Web links

- International Seismological Center, ISC-EHB: On-Line Bulletin data set of the quake from the International Seismological Center, Thatcham, United Kingdom (English).

literature

- Elena Poniatowska , Aurora Camacho de Schmidt, Arthur Schmidt: Nothing, Nobody: The Voices of the Mexico City Earthquake. Temple University Press, Philadelphia 1995, ISBN 1-56639-345-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Mexico City earthquake of 1985. Encyclopædia Britannica , September 16, 2010, accessed on September 20, 2017 (English).

- ↑ a b c 30 years ago: The Mexico earthquake of September 19, 1985. ZAMG , September 18, 2015, accessed on September 21, 2017 .

- ↑ a b 1985: Mexico suffers devastating earthquake. British Broadcasting Corporation , 2008, accessed September 20, 2017 .

- ↑ a b David Adler: The Mexico City earthquake, 30 years on: have the lessons been forgotten? The Guardian , September 18, 2015, accessed September 20, 2017 .

- ↑ JM Espinosa-Aranda, A. Cuéllar, G. Ibarrola, R. Islas, A. García, FHRodríguez, B. Frontana: The Seismic Alert System of Mexico (SASMEX) and their Alert Signals broadcast results . In: Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering . Lisbon 2012, p. 1 (English, online on the website of the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur (PDF; 611 kB)).

- ^ John Enders: The "miracle babies" of Mexico City: 25 years later. Public Radio International , February 5, 2010, accessed September 20, 2017 .