Women's suffrage in Australia

The women's suffrage in Australia was introduced in two of the six later states, as this still independent colonies were: Since 1894 were allowed in South Australia choose regardless of their race under the same conditions as men and women are elected. This made the parliament of the state of South Australia the first in the world for which women were allowed to stand. The women's suffrage for the state of Western Australia followed in 1899, but Aborigines were here excluded.

Federal women's suffrage was introduced in 1902, a year after the Commonwealth of Australia was founded . Although Australia was the second state in the world after New Zealand to give women the right to vote and stand for election on the same terms as men at the federal level, there were restrictions with regard to the Aborigines : female Aborigines were only allowed to participate in the federal elections there, where they were also eligible to vote for the state parliament. This was the case only in South Australia in 1902. The race question played a role in women's suffrage in Australia - unlike in New Zealand: In Queensland and Western Australia it was not until 1962 that a law gave the female Aborigines from these states the right to vote at the federal level; the two states then also carried this over to the election to their state parliaments.

Historical development

In Australia, as in New Zealand, there was no ingrained aristocracy. Rather, an ideal of equality prevailed with the stipulation that people should be judged according to their abilities, especially in a pioneering country, not according to their origin. The hard life of the early days favored women who took adversity and rewarded them with respect and prestige. The origins of Australia as a convict colony also gave the state a masculine atmosphere; there had been female prisoners there too, but they were in the minority. Apart from these, idealists in search of a new society and supporters of the abstinence movement also found themselves in Australia .

In line with this, the first women's movements campaigned for prostitutes and destitute women and declared war on alcohol because it was responsible for poverty in families and violence in relationships. These activities have gradually expanded to include educational opportunities for women. In the last quarter of the 19th century all women had a school education, some of them had formal qualifications.

As in New Zealand, a visit by Mary Clement Leavett in 1885 and by Jessie Ackerman in 1892 , both from the American Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), had a strong effect on women who were already motivated: within ten years there are state associations of the Australian WCTU in all six states. Women's suffrage was immediately on their agenda, but only as a means of controlling the alcohol trade. The following event also follows this line of thought: In 1891 the National Association of Victoria collected 30,000 signatures for a women's suffrage petition. The social reformer Vida Goldstein , then only 22 years old, also promoted the signing. However, the association continued to speak out against passive women's suffrage. The position of the WCTU with regard to the role of women was contradictory: the traditional role of housewife was still propagated, but there was also a call for women to participate in the action in public space. WCTU established women's suffrage groups in four states; Tasmania did not have one, and in New South Wales radical women's suffrage campaigners refused to accept the overall goal of reducing alcohol consumption because they believed it would contradict advocacy for women regardless of their opinion on alcohol. As a result, a women's suffrage association was founded in Sydney in 1891 without any commitment to the goal of reducing alcohol consumption.

Women's suffrage at the federal level

The history of federal women's suffrage is closely related to the emergence of the Commonwealth of Australia . At the first conference on the formation of this federation on March 2, 1891, which was chaired by the state supporter Sir Henry Parkes , the ideas about the right to vote still diverged: They ranged from universal suffrage for men to a regulation that included this in the individual states also wanted to apply the electoral law for the Parliament of the Commonwealth. Although the conference had received a petition from the Woman's Christian Temperance Union calling for universal suffrage for men and women, it was not considered.

New Zealand was still participating in these talks but later decided not to become part of the Commonwealth, but an independent state. His presence at the first and the following conference, which took place in 1897, meant, however, that two of the states represented, namely New Zealand and South Australia , had already introduced women's suffrage. This created the situation that women could either have exercised the right to vote for them in New Zealand and South Australia at the federal level or, if they had opted for male suffrage, would have lost their right to vote. Everywhere in Australia there were supporters for women's suffrage: in the labor movement that was just emerging, in the liberals, in the already existing women's suffrage groups and in the WCTU. Here, too, she showed her own attitude of encouraging women, but at the same time slowing them down: She not only advocated the inclusion of women's suffrage in the constitution, but also the establishment of a ban on alcohol. In South Australia, delegates to the 1897 conference were selected by an open vote. One candidate, Catherine Helen Spence , received 7,000 votes, but that was not enough to be elected; an early testimony to what was evident wherever women's suffrage was newly introduced: women could not count on women to vote for them.

At the Adelaide Conference in 1897 , the well-known arguments in favor of women's suffrage were put forward: women, as members of the Commonwealth that was to be founded, would respect its laws, pay taxes and contribute socially to the welfare of the nation, so they should also have the option, on the same terms as Men to be able to choose their representatives. A first concrete proposal from South Australia envisaged universal suffrage for everyone aged 21 and over; it was rejected by 12:23 votes because it was feared that such a radical step could prevent some of the states from joining the confederation. The conference spoke out in favor of adopting the electoral law applicable in the states for election to parliamentary bodies at the federal level; the only concession to South Australia was that local women would retain their right to vote.

The new parliament met for the first time in Melbourne on May 9, 1901 . Very soon it sought to standardize the electoral law at the federal level. Meanwhile women in South Australia and Western Australia had gained the right to vote. As a result, the electorate in these two states was much larger than that in the four remaining states. Since the two pioneers could not be persuaded to abolish the right to vote for their women, the other four states had no choice but to catch up. Prime Minister Edmund Barton , an opponent of women's suffrage, was in the decisive vote in Britain and was represented by William Lyne , who was a supporter. Although the four states without women's suffrage put forward their counter-arguments, it quickly became clear which direction the development would take and the law was passed unanimously. On June 12, 1902, the bill passed the last hurdle. Although Australia was the second country in the world after New Zealand to give women the right to vote and stand for election on the same terms as men, it was limited to white women. The Commonwealth Electoral Act of 1902 excluded Aborigines, even if this was not immediately apparent from the letter of the law. A regulation stipulated: "No Aborigine [...] may put his name on the electoral roll." The Aborigines were only granted the right to vote by the national government in 1962.

Development in the states

Overview of the introduction of the right to vote for men and women

Male suffrage had been achieved in South Australia, New South Vales, Victoria and Queensland in the 1860s, in Western Australia in 1893 and in Tasmania in 1900. However, since landowners had multiple votes in most states, the wealthy were favored. Labor politicians believed these social injustices were the main problem with current suffrage, not gender inequality. Proponents of women's suffrage were also divided; some of them campaigned for women to have the same property-based inequalities as men, while others advocated universal and equal suffrage.

Even after the introduction of women's suffrage at the federal level, women were not allowed to vote in all states in the election of members of the state parliaments. However, since most issues of immediate concern to women were decided at the state level, obtaining this right to vote continued to be an important goal. Active and passive women's suffrage was introduced in the states between 1894 and 1908: 1894 South Australia , 1899 Western Australia (active women only), 1902 New South Wales , 1903 Tasmania , 1905 Queensland , 1908 Victoria . As a result, after women's suffrage was introduced at the federal level in 1902 in New South Wales, Tasmania, and Victoria, all white women had the right to vote in the federal parliament, but not in the state legislature. When, in the following six years, women were also given the right to vote in these three states in the state level, the female Aborigines were entitled to vote in the state and federal level elections. In Queensland and Western Australia, however, it was not until 1962 that a law gave Aboriginal women federal voting rights; the states then also carried this over to the election to their state parliaments.

South Australia

South Australia had not been settled by convicts, but by British emigrants who were chosen to represent a cross section of English society and the number of women and men equal. They could buy land from the British Crown at a fixed, reasonable price and were a group of hard-working nonconformists who wanted to break out of the traditional restrictions and bigotry of British society. They felt superior to the other Australian colonies. Crime was not as high there as in Western Australia, nor was there great inequalities because a few had got huge lands. In 1856, South Australia introduced a progressive form of government that included the right to vote for men without property barriers for the House of Commons, a three-year term and secret elections. Unlike in other Australian colonies, everyone only had one vote.

Sir Edward Charles Stirling , professor of medicine at the University of Adelaide , had advocated the admission of women to universities under the influence of John Stuart Mill's book The Bondage of Women (1869). When he became a MP, he made a motion for single women to vote. The motion was accepted but did not oblige Parliament to do anything. In 1886 he developed a legislative proposal on the right to vote for single women, which provided for a property barrier for the right to vote, as already applied to the election to the House of Lords. Previously in South Australia there had been no property barriers to suffrage for the House of Commons, and the Trades and Labor Council feared that, in the context of women's suffrage, class-based suffrage would emerge now that women finally had a voice. The middle class would benefit from the property barriers. The council therefore launched a petition for women to vote without property barriers. The petition received 19 votes out of 36 possible. Although this was the majority, it was not enough to change the constitution that would have been necessary. When Stirling lost his mandate the following year, Robert Caldwell proposed that all women over 25 be allowed to vote. The proposal received one vote less than the previous year. The House of Commons was now more polarized and more right-wing orientated. In 1889 another, weakened law on women's suffrage was passed. In 1890, Caldwell introduced a law that allowed married and unmarried women to vote in the upper house, but included property barriers. The Women's Suffrage League supported the proposal, considering it an acceptable compromise on the road to universal suffrage. However, when this initiative was unsuccessful, the Women's Suffrage League announced that it would now only support efforts for universal women's suffrage.

In 1894 active and passive women's suffrage was introduced. This made the parliament of South Australia the first in the world for which women were allowed to stand.

see also below The role of MPs using the example of South Australia

Western Australia

The sparsely populated Western Australia had only received a constitution from the British crown in 1887. Male suffrage was introduced, but property barriers were set. The principle of “one man - one vote” did not apply, the wealthy were preferred. As in New Zealand, the issue of women's suffrage was first brought into focus by Jessie Ackermann, who came to the state in 1892 on behalf of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a prohibition organization, to set up branches. As a result of a gold rush in 1893, many prospectors came to the country and demanded more political say, which they wanted to use to improve the infrastructure. In July 1893, a bill was introduced that provided that male suffrage should be linked to residence in the country, not property. Some Conservative MPs put the right to vote for unmarried women on the agenda. In doing so, they wanted to counteract the change they feared due to the shift from a property-based, more right-wing electorate to the now eligible group of men who were much more heterogeneous and, in their eyes, politically unreliable. More quickly than anywhere else in the world, the Conservative MPs realized that women could act as the pillars of conservative values. Limiting the number of women was also a political calculation: the number of women voters should be limited to unmarried women so that women would not have too much influence over legislation.

After the 1894 elections, Conservative Prime Minister John Forrest and his cabinet formed a closed group on opinion about the right to vote. Supporting women's suffrage would have made them big profits, but it was difficult for them to overcome their fundamental reservations. The opposition disagreed on the issue of the right to vote: The new MPs elected for the gold mining areas under the leadership of Frederick Illingworth complained about the requirement of a certain length of stay for the right to vote, because the prospectors often moved from place to place. They were against the right to vote for women because there were few women in the gold mining areas and women were therefore not a potential voter for Illingworth and his colleagues. This group took a relatively radical position, which in all other countries had led to such groups speaking out in favor of women's suffrage. In Australia, however, it was different, also because the group feared that women's suffrage would increase the power of the cities and bring the prospectors even more behind. Walter James, a Liberal, proposed women's suffrage on principle.

In the elections of 1897, the representatives of the prospectors gained strength. That same year, James proposed a bill on women's suffrage, but met opposition from Illingworth and Forrest. In 1898 he tried again, seeing that Forrest's reservations about women's suffrage were disappearing.

In 1899, the Women's Suffrage League held several meetings for women's suffrage, mobilized the press, and sought widespread support. A meeting on June 16, 1899 resulted in a resolution to the Prime Minister calling for women to vote. He replied that his government was ready to introduce such a law into parliament. Forrest justified his change of heart with an alleged change of opinion in the population, but in reality he feared that the Illingworth group would drive his party of long-established landowners out of government in the next election. He hoped that through women's suffrage, the agriculturally oriented districts would gain in weight and reduce the influence of immigrant gold prospectors. The Constitution Acts Amendment Act of 1899 extended universal suffrage to women. However, Forrest was voted out of office in the next election in 1901, and Walter James was the next Prime Minister to form a Liberal government.

Investigation of possible influencing factors on the development of women's suffrage

Low class awareness

In other states the existence of social classes had hindered the introduction of women's suffrage. There was no entrenched aristocracy in Australia, as most of the residents did not have a long history in which to cement their status. There was also the ideal of equality.

Gender ratio in the population

Since Australia primarily attracted men because of its gold deposits, women were initially clearly in the minority. The demographic situation meant that the vast majority of women got married. The focus of the women's movement was therefore less on the single woman than on the married woman. Feminists saw them as sexually exploited victims of their husband's alcoholism and gambling addiction. The right to vote should give women the power to change their situation, for example by influencing divorce laws.

Even after the introduction of women's suffrage, the political weight of women was lower than that of men, if only because of the numerical proportions: In South Australia, for example, there were 78,972 men versus 59,044 women in the electoral register in 1896; in Western Australia there were fewer than 171,000 eligible voters in 1899 59,000 women. In the other four states, the numbers were less wide apart, but nowhere did women outnumber men as was the case in Britain. In states where women were in a majority in the population, women's suffrage meant that women also had a majority in elections. This was not the case in any of the states where women's suffrage became law very early, in Australia, New Zealand, or any of the states in the western United States. The introduction of supposedly female values into a harsh pioneering society was certainly one of the goals of the women's suffrage movement, but it was clear: if the right to vote would lead to a predominance of women, it would not be until a later generation.

The role of MPs using the example of South Australia

Unlike in many European countries, the women's suffrage movement had the support of parliamentarians such as Sir Edward Charles Stirling . He was elected chairman of the Women's Suffrage League on July 21, 1888 when it was founded. Politically, there was a kind of stalemate in the years around 1893: the Labor Party and the radical liberals were in favor of universal women's suffrage, the moderate liberals advocated restricted women's suffrage, and the conservatives were against both. When the first three Labor Party members, all of whom were in favor of women's suffrage, were elected to the House of Lords, progress slowly began. In 1893 eight members of the Labor Party were elected to the House of Commons. They supported the strong liberal government of Charles Kingston . Although he had originally spoken out against women's suffrage, he surprisingly announced that he would not only introduce a women's suffrage law, but also make its continuation dependent on the outcome of a referendum in which women would also be allowed to vote. Although the referendum found a majority, it was not a majority that would have been sufficient for the necessary constitutional amendment. The most important change, however, was demographic. The population growth in Adelaide led to dwindling support for the Conservatives . By the time a third of the House of Lords were re-elected in 1894, the number of Liberal and Labor MPs had increased so that the House of Lords was no longer in the hands of the Conservatives, which was an unusual situation.

In 1894 a bill was introduced into the House of Lords, which provided active women's suffrage on the same terms as men 's suffrage, but excluded passive voting rights. At an advanced point in the deliberations, the arch-conservative MP Ebenezer Ward requested that the right to vote for women be included in the draft; he assumed that such an extreme bill would by no means find a majority. The supporters of the draft were annoyed, saw through Ward's intentions and, despite the change, voted for the proposal; thus the passive right to vote for women, which was achieved here for the first time in a parliamentary body, was an unexpected blessing. Historian Audrey Oldfield commented: "Australian women were given the right to stand by their opponents!" Ultimately, clever tactics also helped the bill to win: An older and frequently vacillating proponent of the bill always left the deliberations around 11 p.m. All the opposition had to do was extend their speeches until after 11 p.m. for the session to be adjourned. At the crucial session, however, an insider stopped the MP in the lobby, engaged him in conversation, and finally managed to get him back into the hall. At the third and final reading on December 18, 1894, the draft became law. He received royal approval the following year.

Political calculation

Women's suffrage became law in New Zealand, South Australia and Western Australia because a party with government responsibility had got into political trouble and feared losing a majority in the next election. The profound change in the electorate presented itself to her as an anchor of hope. This law did not apply in other states, otherwise the Tories in 1884 in Great Britain would also have gone this way. Their conservative attitude prevented them from seriously considering this possibility.

Organizations

The women's suffrage organizations supported the introduction of women's suffrage in Australia, but played no decisive role in its success. None of the women's organizations had political power.

The WCTU put the issue on the political agenda. But she soon found that her main concern, prohibition , was hampering efforts for women to vote. In some areas there were no other women's organizations, and so the WCTU also attracted women who wanted to campaign for women's suffrage, but not against prohibition. Based on this knowledge, the WCTU changed the weighting and postponed the fight against alcohol abuse.

In some places there were women's suffrage organizations for which prohibition was not a goal from the start. In Victoria, for example, there was the anti-Christian Victorian Women's Suffrage Society , which held the Church to blame for many troubles women had.

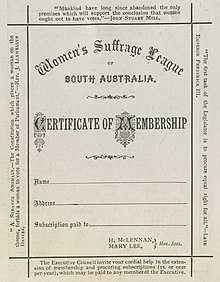

The women's rights activist Mary Lee played a special role in networking the organizations that advocate women's suffrage . Since 1883 she had been secretary of the women's department of the Social Purity Society , which worked to improve the situation of young women, who often had been working before 10 or 12 years. Because Mary Lee felt that if women were allowed to vote, the Social Purity Society convened a meeting of the Young Women's Christian Association in 1888 to establish the Women's Suffrage League, with Mary Lee as executive director. All those who were in favor of women's suffrage, but could not identify with the strict abstinence requirement of the Australian WCTU, could find themselves here. The Women's Suffrage League called for active voting rights for all women, but emphasized that passive voting rights were not one of their goals. The Trades and Labor Council , with which Mary Lee was associated as chair of the newly formed women's union, supported candidates from political liberals who shared her views. In the five years from its first appearance on the political agenda to the election of 1890, women's suffrage had become a central issue through intensive work by the organizations.

Foreign influence

The introduction of women's suffrage in neighboring New Zealand had a positive effect on aspirations in Australia, especially in South Australia and Western Australia.

Connection to pioneering history

The comparatively radical stance of the legislators in Australia and New Zealand and the rapid development towards women's suffrage showed how much such an approach corresponded to the pioneering spirit. The colonies attracted people who were interested in social experiments and wanted to make them a reality. The writings of John Stuart Mill laid the spiritual basis for advocating women's suffrage.

Although it cannot be inferred from developments in Australia that a national crisis is necessary for the introduction of women's suffrage, it is remarkable that new constitutions and even a new state emerged at the same time.

Importance of Race in Australian Politics and Society

The race question played a role in women's suffrage in Australia, unlike in New Zealand . But it did not prevent the early introduction of women's suffrage at the federal level. The proposal to introduce universal suffrage for all British subjects when the Commonwealth was founded went too far for the delegates from Western Australia and Queensland. They argued that if there were universal suffrage with the Aborigines , savages would vote, which would be offensive to white women. There was disagreement over whether people with both Aboriginal and whites in the family tree were allowed to vote, but not about Maoris , who automatically had a right to vote if they had citizenship. One parliamentarian justified the difference with the fact that Aborigines are not as intelligent as Maoris, yes, that there is no scientific evidence that Aborigines are human at all. The opponents achieved that the parliament orientated itself to the electoral law, as it applied in the federal states: Female Aborigines had the right to vote for the federal parliament only where they were already entitled to vote for the state parliament. In contrast to the other states, female and male Aborigines in South Australia had the right to vote from 1902 on both at the federal level and - as before - at the state level. Until women were allowed to vote in state elections, certain states were allowed to vote for Aboriginal men but not for white women. Women in favor of women's suffrage accused lawmakers of placing all white women in a worse position than Aboriginal men. In Queensland and Western Australia it was not until 1962 that a law gave Aboriginal women from these states the right to vote at the federal level; the two states then also carried this over to the election to their state parliaments.

Consequences of the introduction of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage as a basis for the political representation of women

Women saw the gain in gaining the right to vote. Women saw themselves as a new and independent political force who wanted to bring their concerns into the political landscape without founding parties of their own. This was done, among other things, by sending out questionnaires on women-specific issues to election candidates from all parties.

As in other states, in Australia, too, the acquisition of women's suffrage in no way meant that women expressed their solidarity with the candidates in their voting behavior and voted for them. Many of them showed little interest in politics and did not base their votes on gender, but on their husbands or their class. It was therefore only decades later that women gained parliamentary seats.

At the state level

In 1921 Edith Cowan gained a seat in the Legislative Assembly , the lower house of Western Australia. This made her the first woman ever to be elected to an Australian parliament and the second woman to be elected to a parliament of the British Empire . It is thanks to your legislative initiative from 1923 that women were given access to professions and activities that they had previously been denied, for example lawyers to defend defendants in court.

At the national level

Dorothy Margaret Tangney was the first woman to be elected to the national parliament, the House of Representatives. The election was on August 21, 1943, the first session on September 23, 1943.

Social and legal improvements for women

Feminists like Louisa Lawson and Rose Scott saw women's suffrage as a step towards independence for women from men. When women were allowed to vote, the focus was on the goal of a welfare state that significantly improved the social situation of women and especially of wives and mothers. Women's hospitals were established, children's playgrounds were set up and maternity benefits were introduced. The availability of alcohol, which women considered an important factor in the difficult domestic situation of many wives, was restricted. Inheritance and guardianship rights for women and property rights of married women were also on the agenda.

Commitment to the Aboriginal people

The clear orientation of the women's movement towards the interests of mothers after receiving the right to vote led to a sustained campaign against the practice of withdrawing Aboriginal children from their families . Women's rights activists like Jessie Street and Ada Bromham also campaigned for Aboriginal suffrage, land restitution and better educational opportunities for the Aborigines .

International engagement of Australian feminists

Australian feminists also advocated women's rights in the UK and other Commonwealth of Nations. Vida Goldstein was invited to a lecture tour in the United Kingdom in 1911, during the course of which it was decided on May 11, 1911 in London to found the Australian-New Zealand Committee for Women's Suffrage ( The Australian and New Zealand Voters' Committee , ANZWVC). The British-Australian teachers Harriet Christina Newcomb and Margaret Emily Hodge founded the Woman Suffrage Union - British Dominions Overseas on their travels to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Canada in 1912, 1913 and 1914 , which became British Dominions Woman Suffrage in mid-1914 Union (BDWSU) renamed. The ANZWVC was absorbed into it. The organization was particularly concerned with Indian women and sought to bring their concerns to the fore in Great Britain. In the period around World War I in particular , Australian feminists tried to help British women achieve the rights they had already gained, while also helping non-white women in other Commonwealth countries.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 132.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 119.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 25.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 120.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 130.

- ↑ Audrey Oldfield: Woman Suffrage in Australia. A Gift or a Struggle? Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1992, p. 60, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 130.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 131.

- ↑ Patricia Grimshaw: Settler anxieties, indigenous peoples and women's suffrage in the colonies of Australie, New Zealand and Hawai'i, 1888 to 1902. In: Louise Edwards, Mina Roces (ed.): Women's Suffrage in Asia. Routledge Shorton New York, 2004, pp. 220-239, p. 226.

- ↑ Patricia Grimshaw: Settler anxieties, indigenous peoples and women's suffrage in the colonies of Australie, New Zealand and Hawai'i, 1888 to 1902. In: Louise Edwards, Mina Roces (ed.): Women's Suffrage in Asia. Routledge Shorton New York, 2004, pp. 220-239, p. 229.

- ^ Anne Summers: Damned Whores and God's Policy. Camberwell, Victoria, Australia, Penguin 2002, p. 420, quoted from Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 132.

- ↑ Caroline Daley, Melanie Nolan (Eds.): Suffrage and Beyond. International Feminist Perspectives. New York University Press New York 1994, p. 349.

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , pp. 23-28.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 121.

- ↑ The bondage of women

- ↑ a b c d Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 122.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 123.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 125.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 126.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 127.

- ↑ a b c d Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 128.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, pp. 31-36.

- ^ William Pember Reeves: States Experiments in Australia and New Zealand. , Volume 1, London, Grant Richards 1902, page 137, quoted from Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 133.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 133.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 124.

- ↑ Audrey Oldfield: Woman Suffrage in Australia. A Gift or a Struggle? Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1992, p. 53, quoted from Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 125.

- ↑ Elizabeth Mansutti: Mary Lee 1821-1909 . Adelaide, Openbook 1994, p. 17, quoted from Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 123.

- ^ King O'Malley, April 23, 1902, in a House of Representatives debate, Commonwealth Franchise Bill parliamentary records , 11929, quoted from Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 131.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 13.

- ↑ Defining Moments. Edith Cowan , (English), at National Museum of Australia . Retrieved May 14, 2019

- ↑ Edith Cowan 1861-1932 (PDF), on civicsandcitizenshio.edu.au. Retrieved August 2, 2020

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 15.

- ^ A b c Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 12.

- ^ A b Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 30.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 20.

- ^ Marilyn Lake: Getting equal. The history of Australian feminism. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ Angela Woollacott: Australian women's metropolitan activism. From suffrage, to imperial vanguard, to Commonwealth feminism. In: Ian Christopher Fletcher, Laura E. Nym Mayhall, Philippa Levine: Women's Suffrage in the British Empire. Citizenship, nation, and race. Routledge, London and New York 2000, pp. 207-223, ISBN 0-415-20805-X , pp. 209.

- ↑ a b Angela Woollacott: Australian women's metropolitan activism. From suffrage, to imperial vanguard, to Commonwealth feminism. In: Ian Christopher Fletcher, Laura E. Nym Mayhall, Philippa Levine: Women's Suffrage in the British Empire. Citizenship, nation, and race. Routledge, London and New York 2000, pp. 207-223, ISBN 0-415-20805-X , p. 210.

- ↑ Angela Woollacott: Australian women's metropolitan activism. From suffrage, to imperial vanguard, to Commonwealth feminism. In: Ian Christopher Fletcher, Laura E. Nym Mayhall, Philippa Levine: Women's Suffrage in the British Empire. Citizenship, nation, and race. Routledge, London and New York 2000, pp. 207-223, ISBN 0-415-20805-X , p. 219.