Women's suffrage in Australia and Oceania

The women's suffrage in Australia and Oceania was reached very early in three states: New Zealand was the first independent state with women's suffrage. On September 8, 1893, it was decided in parliament. Australia was indeed for New Zealand , the second country in the world, which at the federal level women's active and passive at the same conditions were right to vote as men, but there was the introduction in 1902 restrictions on the Aborigines : Female Aborigines were allowed to only there in the elections participate in the federal parliament, where they were also entitled to vote for the parliament of the respective state. This was the case only in South Australia in 1902 . The race question played a role in women's suffrage in Australia - unlike in New Zealand: In Queensland and Western Australia it was not until 1962 that a law gave the female Aborigines from these states the right to vote at the federal level; the two states then also carried this over to the election to their state parliaments. The Cook Islands were the first state in which women voted. This happened on October 14, 1893. The South Pacific was thus a little-noticed pioneer in matters of democracy.

Individual states

Australia

Women's suffrage in Australia was introduced in two of the six later states when they were still independent colonies: Since 1894, women in South Australia have been allowed to vote and be elected under the same conditions as men, regardless of race. This made the parliament of the state of South Australia the first in the world for which women were allowed to stand. Women's suffrage for the state of Western Australia followed in 1899, but Aboriginal people were excluded.

Federal women's suffrage was introduced in 1902, a year after the Commonwealth of Australia was founded . Although Australia was the second state in the world after New Zealand to give women the right to vote and stand for election on the same terms as men at the federal level, there were restrictions with regard to the Aborigines : female Aborigines were only allowed to participate in the federal elections there, where they were also eligible to vote for the state parliament. This was the case only in South Australia in 1902. The race question played a role in women's suffrage in Australia - unlike in New Zealand: In Queensland and Western Australia it was not until 1962 that a law gave the female Aborigines from these states the right to vote at the federal level; the two states then also carried this over to the election to their state parliaments.

Cook Islands

The Cook Islands are the first state in which women voted. This happened on October 14, 1893. The South Pacific was thus a little-noticed pioneer in matters of democracy.

Historical development

In the 1880s, the Cook Islands attracted the attention of the Māoris and some major European powers. They were the target of New Zealand traders and missionaries and had to defend themselves against Peruvian slave traders. Frederick Moss, a former Member of Parliament from Auckland who was appointed a British resident by New Zealand , made the island part of the British Empire . As a contemporary noted, “He had far-reaching ambitions, and the fact that the island was nowhere near big enough to fill them dampened his vigor.” Among other reforms, Moss introduced an elected parliament, including that of women was chosen. Moss proudly wrote: "The Cook Islands Parliament is the only free Maori parliament that has ever been attempted to be established." Island democracy was utopian in that it could only have functioned if the chiefs had given up their power; but the chiefs continued to rule over their villages. They were able to influence the elected MPs, mainly because Moss' plans for secret suffrage were undermined.

Universal suffrage was not officially guaranteed until three days after the New Zealand Election Act , but the women of Raratonga voted before the New Zealanders on October 14, 1893.

Marguerite (Margaret) Nora Kitimira Brown Story was elected as the first woman to the Legislative Assembly in 1965, still in colonial times, and was its chairman from 1965 to 1979 and then again in 1983. The first female member of the government was Fanaura Kingsone , Minister of the Interior and Postal Service , who was appointed in 1983 .

Importance of women in the islands

The importance of women on the islands is documented by sources: in 1890 four of the five chiefs of Rarotonga were women, and they greatly appreciated the fact that the British navy was subordinate to a queen. Dick Scott, the historian of the Cook Islands, reports how the female chiefs themselves had already accepted the title of queen and called their houses palaces : “The flattery customary at courts was meticulously executed here too, and a whole series of easily impressed tourists and Travel writers presented the people at home with reports of how they had been received in the royal apartments. "

The granting of the right to vote to women in the South Seas fitted into a society in which women from respected families appeared publicly and had power. to occur. The separation into a male domain, which included politics or the organization of public life, and a female, restricted to the house, did not exist on Rarotonga (and probably on many other South Sea islands). Only the fight was reserved for men. This decimated the male population and meant that community life had to be shouldered by a community with a clear surplus of women. The lack of information on the early reign in the South Seas supports the correctness of John Markoff's remark: "The history of democracy is largely due to the creativity of places that historians have barely explored."

Fiji

On April 17, 1963, while still under British administration, women were given the right to vote and stand for election.

In 1970 Fiji became independent and women were granted the right to vote.

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Two women, 1970. Before independence, Adi Losalini Dovi was elected to the legislative body of the colonial government in 1966 .

Kiribati

Before independence, under British administration, women were given universal suffrage in the electoral laws ( Gilbert & Ellice Islands Colony Electoral Provisions Order , 1967) and the Constitution on November 15, 1967. After independence in 1979 this was confirmed.

Passive women's suffrage: November 15, 1967 (see also above)

First election of a woman to the colonial parliament: Tekarei Russell , 1971. First election of women to the national parliament: Fenua Tamuera , July 25, 1990. (by-election), Koriri Muller , 1992 (by-election). Teima Onorio , September 30, 1998; first woman to be elected to parliament in a regular election.

Marshall Islands

Under the administration of the USA, the right to vote for women was guaranteed on May 1, 1979 and confirmed when independence was achieved in 1986.

Passive women's suffrage: May 1, 1979

First election of a woman to the colonial legislative body: Evelyn Konou , 1979; in the national parliament: Evelyn Konou, 1979

Micronesia

Before independence, women were given active and passive voting rights on November 3, 1979. When independence was achieved in 1986, these rights were confirmed.

Passive women's suffrage: November 3, 1979

First election of a woman to the national parliament: none until 2019.

Nauru

Active and passive women's suffrage was introduced on January 3, 1968.

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Ruby Dediya , December 1986.

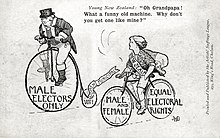

New Zealand

Women's suffrage in New Zealand was initially only introduced as an active right to vote in 1893 . However, New Zealand was the first independent state in which women were allowed to vote at all . The passive female suffrage followed in 1919 and the first choice of a woman to the national parliament fourteen years later. Until the mid-1980s, the number of women MPs was in the single digits. In the 2017 general election, 38% were women. In the early 21st century, women held each of the key political positions at least once. The commitment of politicians and activists for women's suffrage was based, among other things, on the ideas of the British philosopher John Stuart Mill and the efforts of the abstinence movement , which came to New Zealand from the USA. The introduction of women's suffrage was greatly facilitated by the fact that the party landscape and class antagonisms had not yet consolidated in the young state and that the indigenous population had already been granted the same rights as immigrants when it came to male suffrage. The numerous petitions accelerated the development. Between 1878 and 1887, several bills that provided the right to vote for all women or at least for the wealthy among them failed. In 1891 and 1892, bills aimed at making all women voters were given a majority in the House of Commons ; the bills were rejected in the more conservative upper house .

Palau

Before independence, under US administration, women had the right to vote on April 2, 1979. It was confirmed upon independence in 1994.

Passive women's suffrage: April 2, 1979.

First election of a woman to the national parliament: House of Delegates Akiko Catherine Sugiyama , 1975; Senate: Sandra Sumang Pierantozzi , 1997

Papua New Guinea

Prior to independence, under Australian administration, women were given the right to vote on February 15, 1964. This right was confirmed upon independence in 1975.

Passive women's suffrage: February 27, 1963

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Josephine Abaijah , 1972 Colonial Legislative Body, House of Assembly; national parliament: three women, July 1977

Solomon Islands

During the colonial days under British administration, women were guaranteed the right to vote in April 1974. This right was confirmed upon independence in 1978.

Passive women's suffrage: 1974

First election of a woman to the colonial parliament: Lilly Ogatina , 1965; in the national parliament: Hilda Auvi Kari , 1989

Samoa

In 1948, still under New Zealand administration, women were given restricted voting rights at the national level: only clan heads , known as Matai , and non-Samoans (European or Chinese voting) who had completed all the formalities for obtaining citizenship and the right of residence were allowed to vote.

In 1961 the country became independent.

Between 1962 and 1990 the right to vote was limited to the Matai . Only two of the 49 members of the Legislative Assembly (Fono) were elected by universal suffrage. The vast majority of the Matai have always been men. Since the 1960s, however, the advancement of women's education, which had led to higher educational degrees and qualifications, had increased the number of female Matai . Only a small number of women had been elected to the legislative assembly since 1962. After a referendum in October 1990, universal suffrage was introduced. The first elections under the changed conditions were held in April 1991. Before general active and passive suffrage was introduced in October 1990, only clan heads had active and passive suffrage.

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Fiame Naomi Mata'afa , Matatumua Maimoaga Vermeulen , both April 199; before that there was a woman in parliament in 1964, the details of the circumstances could not be determined.

Tonga

Before independence, under British administration, women were given the right to vote in 1960. These rights were confirmed when independence was achieved in 1970.

Passive women's suffrage: 1960

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Papiloa Bloomfield Foliaki , 1978; Princess Mele Siulikutapu Kalaniuvalu photo file , 1975

Tuvalu

Under British administration, women were given the right to vote on January 1, 1967. With independence in 1978 this right was confirmed.

Passive women's suffrage: January 1, 1967

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Naama Maheu Laatasi , September 1989

Vanuatu

Before independence, under the administration of the Anglo-French Condominium New Hebrides , women were guaranteed the right to vote in November 1975. This right was confirmed on July 30, 1980 when independence was obtained.

Passive women's suffrage: November 1975

First election of a woman to the national parliament: Two women, November 1987

Individual evidence

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 132.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 132.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. , Page 26.

- ^ Dick Scott: Years of the Pooh-Bah: A History of the Cook Islands. CITC Raratonga, 1991, p. 44, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. , Page 26.

- ^ Dick Scott: Years of the Pooh-Bah: A History of the Cook Islands. CITC Raratonga, 1991, p. 58, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. , Page 26.

- ^ Dick Scott: Years of the Pooh-Bah: A History of the Cook Islands. CITC Raratonga, 1991, p. 61, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. , Note 24, p. 444.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 281.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 25.

- ^ Dick Scott: Years of the Pooh-Bah: A History of the Cook Islands. CITC Rarotonga, 1991, p. 43, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Page 25.

- ^ John Markoff: Margins, Centers, and Democracy. The Paradigmatic History of Women's Suffrage. In: Signs: JOurnal of Women in Cluture and Society , Volume 29/1, 2003, p. 109, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. , Page 26.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 129.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. April 17, 1963, accessed October 1, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 130.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. November 15, 1967, accessed October 3, 2018 .

- ^ A b c Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 212.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. May 1, 1979, accessed October 5, 2018 .

- ^ A b c Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 252.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved October 5, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 258.

- ^ Pacific Women in Politics. Country Profiles: Federated States of Micronesia. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 270.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. April 2, 1979, accessed October 5, 2018 .

- ^ A b c Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 297.

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 300.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. February 15, 1964, accessed October 5, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, pp. 300/301.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved October 6, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 348.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved October 6, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d e f June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 261.

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 329.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, pp. 329/330.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Accessed October 7, 2018 (English).

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 381.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 382.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. January 1, 1967, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ^ A b c Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 390.

- ^ Dieter Nohlen, Florian Grotz, Christof Hartmann (eds.): South East Asia, East Asia and the South Pacific. (= Elections in Asia and the Pacific. A Data Handbook. Volume 2). Oxford University Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-19-924959-8 , p. 825

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. July 30, 1980, accessed October 13, 2018 .

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 414.

- ↑ a b Dieter Nohlen, Florian Grotz, Christof Hartmann (eds.): South East Asia, East Asia and the South Pacific. (= Elections in Asia and the Pacific. A Data Handbook. Volume 2). Oxford University Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-19-924959-8 , p. 836

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 415.