Glycemic Index

The glycemic index (GI) is a measure of the effect of a carbohydrate-containing food on blood sugar levels . Sometimes the term Glyx is used for this . ( Formula symbol or ). The higher the value, the more sugar there is in the blood.

A similar parameter is the insulin index , which indicates the insulin level instead of the blood sugar level.

The term glycemic index was introduced in the 1980s as part of diabetes research. It was found that white bread, for example, causes blood sugar to rise more sharply than household sugar after consumption. But the difference could not be explained by the structure of the carbohydrates (i.e. complex or small molecule).

There are several diets that attach importance to the GI, for example the Montignac method , the Glyx diet and the Logi method . Recent research confirms the relevance of the GI for the therapy of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and obesity. With regard to the change in weight, there are contrary studies, since the GI is individually very variable and it can a. depends on the intestinal flora .

determination

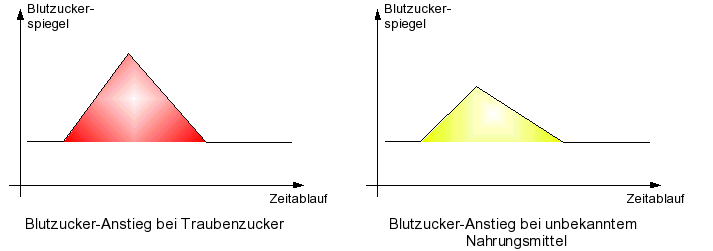

The glycemic index indicates in numbers the blood sugar-increasing effect of carbohydrates or foods. The blood sugar-increasing effect of grape sugar serves as a reference value (100). A test person eats enough glucose or so much of the food to be tested that 50 g of carbohydrates are contained in each portion consumed. In the picture, the change in blood sugar is shown as a black line (here a simplification!). The glycemic index is defined using the quotient of the areas (mathematically: the integrals ) under the line of blood sugar values during the first two hours after eating a meal.

A GI of 50 means that the blood sugar integrated over time in the food being assessed makes up only half of the blood sugar from dextrose, i.e. here the yellow area is half the size of the red area.

Foods containing carbohydrates, which cause a rapid and high rise in blood sugar, do not necessarily have a high glycemic index. If the blood sugar level falls again quickly after the rapid, high rise, the index can be low despite the briefly high blood sugar level. And foods that increase blood sugar levels slightly or slowly after consumption do not necessarily have a low glycemic index. If the small increase continues for a long time, the index can still be high. For a reliable statement about the effect of a food on a person's blood sugar level, the blood sugar level diagram is decisive and far more informative than the index.

In America there are some GI tables in circulation that put the GI in relation to white bread, which then has a GI of 100. However, the values can be converted into one another using the factor 0.7.

The value from which the GI can be regarded as high is assessed differently for different diets.

In general, the following classification is used:

- High is a GI greater than 70

- The mean are GI values between 50 and 70

- A GI is less than 50.

This classification is also used, for example, in the Glyx diet and Logi method .

The Montignac method uses a different classification . Food with a GI value greater than 50 is bad, between 35 and 50 good and with a GI value less than 35 is very good.

Glycemic Load (GL)

In contrast to the pure Glyx, the so-called glycemic load (GL) also takes into account the carbohydrate density of the individual food. For example, cooked carrots and baguette bread have roughly the same glycemic index (≈70), but the carbohydrate density of carrots, at 7.1 g per 100 g of food, is significantly lower than that of baguette bread at 51.0 g per 100 g. The glycemic load is significantly lower with carrots than with bread. As a result, 100 g of cooked carrots will cause a far smaller increase in blood sugar levels than 100 g of baguette bread, even though the underlying glycemic index is the same.

Importance of the GI for athletes

The main factor influencing the GI is the level of training . Which food is consumed is of secondary importance.

The knowledge about the GI of food contributed to a better understanding of the energy supply during physical exertion. This knowledge is used by both endurance and strength athletes. Studies have shown that consuming high GI foods 30 to 60 minutes before exercise leads to premature fatigue. After an insulin spike, right at the beginning of the exercise there is a drop in the glucose level and an emptying of the glycogen stores, as well as a rapid breakdown of free fatty acids . Instead, high-carbohydrate foods with a medium GI should be consumed in order to ensure a constant supply of energy from carbohydrates, which is only possible if there is no high insulin level. It has also been found that taking a not excessive amount of carbohydrates with a high GI is beneficial immediately after physical exertion, as this gets into the blood particularly quickly and also accelerates the absorption of calcium and magnesium ions in the intestine, which leads to a very rapid replenishment of energy reserves. These are not intended for the next load, but should be available to the body during recovery.

Importance of the GI for the obese

Food with a high GI leads to high or long-lasting blood sugar levels , which then leads to a large amount of insulin . This in turn leads to an increase in the absorption of glucose in muscle and fat cells and also stimulates fat storage and carbohydrate storage in the form of glycogen . Therefore, some authors assume that the consumption of foods with a high GI results in an undersupply of energy carriers in the blood ( hypoglycaemia ) after about 2 to 4 hours . This in turn stimulates the consumption of foods that increase blood sugar quickly and thus allegedly lead to a vicious circle and ultimately to obesity. In fact, hypoglycaemia does not occur in healthy people, as carbohydrates can also be released from the glycogen stores if necessary. There are conflicting studies on this theory.

In general, however, it is assumed that the sharp drop in blood sugar levels in foods with a high GI leads to changes in the digestive process, including a feeling of hunger and consequent re-ingestion. Switching to foods with a lower GI and glycemic load (GL) appears to be an effective therapeutic measure for overweight people. In addition to the effect on obesity, the direct connection between GI and type 2 diabetes mellitus ( adult diabetes ) and cardiovascular diseases, especially in children and adolescents, is pointed out.

The German Nutrition Society cites several studies in a statement, some of which suggest an increase in the risk of developing obesity depending on the glycemic index. This is more true of women than men. A certain influence on various diseases of civilization such as coronary heart disease and the development of cancer is suspected.

Other studies come to the conclusion that for the breakdown of adipose tissue it is less the insulin level than the energy balance of food intake that is decisive. The consumer advice center North Rhine-Westphalia states: “There is no scientific justification for implementing the GI concept and, for example, advising against the consumption of potatoes and (whole-grain) cereal products with a high GI or high GL. The influence on the reduction of obesity is controversial and has so far hardly been systematically investigated. ”As part of an intervention study by the pan-European DIOGENES (Diet, Obesity and Genes) project, it was shown that a diet with a low glycemic index has no advantage in terms of (re -) brings an increase in body weight.

Influencing factors and effects on the metabolism

- The glycemic index was developed as a laboratory parameter for research purposes and is not very practical for everyday nutrition. This is because it describes the blood sugar reaction to the intake of 50 g of carbohydrates, which are supplied through a certain food, and not the reaction to 100 g of food.

Example: The glyx of boiled carrots is 70 (recent studies indicate a lower value). Since carrots are very low in carbohydrates, around 800 grams of carrots would have to be eaten to get 50 g of carbohydrates. This is not the case with foods rich in carbohydrates: baguette bread also has a glyx of 70, but a small amount of 104 g is enough to supply the desired amount of 50 g of carbohydrates. Based on the GI of 70, the scientific statement is: Consuming 104 g of baguette bread leads to the same increase in blood sugar as consuming 800 g of carrots. - The actual blood sugar response depends to a large extent on which foods are consumed together in a meal. The course of the blood sugar level depends less on the sum of the GI values of the foods consumed together, and more on a large number of ingredients and their interactions.

- There are strong individual variations: the same food does not cause the same rise in blood sugar levels in different people. Different values have been measured in studies even in the same person.

- Fats delay gastric emptying and thus dampen the glycemic response, as the carbohydrates do not reach the small intestine until later, where they are absorbed.

- The GI can vary greatly depending on the type of preparation. Heating, boiling, and chopping raise the GI. Pasta that has been cooked for just five minutes has less of an impact on the blood sugar response (GI: 37) than pasta that has been cooked for 10–15 minutes (GI: 44) or even 20 minutes (GI: 61). Precise information on the GI for processed products is therefore hardly possible.

- Potatoes have a high glycemic index. With boiled potatoes (and especially with some waxy varieties) it is sometimes significantly lower than with mashed potatoes and baked or deep-fried potatoes. A Canadian study showed that children still consume up to 40% fewer calories when a meal is served with mashed potatoes as a side dish and that the glucose and insulin values after meals are lower when the side dish consisted of French fries (both in Compared to pasta and rice dishes).

Web links

- Glycemic index and glycemic load (German Nutrition Society (DGE) e.V., Bonn) (PDF; 89 kB), accessed on January 9, 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ LS Augustin et al .: Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Conso . PMID 26160327

- ↑ a b SK Das, CH Gilhooly, JK Golden, AG Pittas, PJ Fuss, RA Cheatham, S. Tyler, M. Tsay, MA McCrory, AH Lichtenstein, GE Dallal, C. Dutta, MV Bhapkar, JP Delany, E. Saltzman, SB Roberts: Long-term effects of 2 energy-restricted diets differing in glycemic load on dietary adherence, body composition, and metabolism in CALERIE: a 1-y randomized controlled trial . In: Am J Clin Nutr. , 2007 Apr, 85 (4), pp. 1023-1230, PMID 17413101 .

- ^ S. Vega-Lopez, LM Ausman, JL Griffith, AH Lichtenstein: Interindividual variability and intra-individual reproducibility of glycemic index values for commercial white bread ; In: Diabetes Care , 2007 Jun, 30 (6), pp. 1412-1417. Epub March 23, 2007.

- ↑ Individually adapted nutrition . Deutschlandfunk , current research

- ^ S Mettler, F Lamprecht-Rusca, N Stoffel-Kurt, C Wenk, PC Colombani: The influence of the subjects' training state on the glycemic index . In: European Journal of Clinical Nutrition . tape 61 , no. 1 , January 2007, p. 19-24 , doi : 10.1038 / sj.ejcn.1602480 .

- ^ CK Rayner, M. Samsom, KL Jones, M. Horowitz: Relationships of Upper Gastrointestinal Motor and Sensory Function With Glycemic Control . In: Diabetes Care . 2001 Feb; 24 (2): 371-381.

- ↑ SB Roberts: High-glycemic index foods, hunger, and obesity: is there a connection? Nutr Rev. 2000 Jun; 58 (6): 163-169.

- ^ DS Ludwig: Novel treatments for Obesity . In: Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. , 2003, 12 Suppl, p. S8.

- ↑ a b c d Daniela Strohm, Bonn: Glycemic index and glycemic load - a concept relevant to nutritional practice in healthy people? (PDF) Scientific statement of the DGE

- ↑ Consumer advice center North Rhine-Westphalia: ABC der Schlankmacher ; 2004

- ↑ Wim Saris u. a .: The Diogenes Project - Diet, Obesity & Genes Targeting the obesity problem: seeking new insights & routes to prevention . (PDF; 236 kB) Press release, June 2, 2008.

- ↑ Stefan Weigt: What is the glycemic index good for? In: UGB-Forum special diets currently assessed, 2007, volume, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ R. Akilen, N. Deljoomanesh, S. Hunschede, CE Smith, MU Arshad, R. Kubant, GH Anderson: The effects of potatoes and other carbohydrate side dishes consumed with meat on food intake, glycemia and satiety response in children. In: Nutrition & Diabetes. Volume 6, February 2016, p. E195, doi: 10.1038 / nutd.2016.1 , PMID 26878318 , PMC 4775821 (free full text): “The physiological functions of CHO foods consumed ad libitum at meal time on food intake, appetite, BG, insulin and gut hormone responses in children is not predicted by the GI. "