Guardian of the Constitution

Guardian of the Constitution is a term from German constitutional history . In the Weimar Republic it was used repeatedly for the Reich President . In retrospect, one can also see a constitutional guardian in the monarchs in the individual German states. The idea is promoted by the fact that the oath of office of a head of state may mention protection or respect for the constitution.

Alternatively, a constitutional court is seen as the guardian of the constitution. If Carl Schmitt rejected this view, it has clearly established itself in the Federal Republic of Germany . However, there are also voices criticizing the Federal Constitutional Court for interfering too much in legislation . In addition, the term is sometimes used for other, for example European courts or for administrative institutions of the protection of the constitution .

Weimar Republic

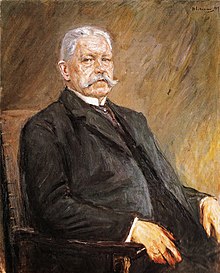

Carl Schmitt

In 1929, the influential legal scholar Carl Schmitt published a book entitled: "The Guardian of the Constitution". In it he draws on historical models, compares the monarchical with the republican-democratic state, criticizes the pluralism of the modern party state and examines which state organs are suitable for the role of constitutional guardian.

Schmitt was skeptical of a constitutional court. The independence of judges is only the other side of judicial compliance. On the basis of the constitution, however, such a bond cannot arise. One would put an unbearable burden on the judiciary if one were to entrust all the tasks that are to be resolved in a politically neutral way. Nowadays the judicial review right would no longer be directed against the orders of a monarch, but against parliament. A constitutional court would be a kind of further parliamentary chamber . In any case, one must pay attention to how a constitutional court is elected and how it is composed. Otherwise politics could influence the organ through new judges appointed (for example after an increase in the number of judges).

Instead, Schmitt saw the Reich President as the body that was already a guardian of the constitution according to the Weimar Constitution :

“The Reich President is at the center of an entire system of party-political neutrality and independence built on a plebiscitary basis. The state order of today's German Reich is dependent on him to the same extent that the tendencies of the pluralistic system make normal functioning of the legislative state difficult or even impossible. "

Schmitt refers to the extensive powers of the Reich President and his oath to uphold the constitution (Art. 42 WRV). This “authentic constitutional word” should not be ignored. In addition, there is the election by the entire German people, its right to dissolve the Reichstag and its role in referendums . The Reich President thus becomes a counterbalance to pluralism in politics and economics and a guarantee for the unity of the people. That is at least the attempt of the constitution. Schmitt ends the work with the sentence: "The existence and duration of today's German state are based on the fact that this attempt succeeds."

Constitutional reality

In the summer of 1922 the Reichstag passed the Republic Protection Act as a reaction to the murder of Reich Foreign Minister Walter Rathenau . The Bavarian state government opposed the implementation of the law by means of a state ordinance. Reich President Friedrich Ebert referred to himself for the first time in a letter to the state government of July 27, 1922 as the "guardian of the constitution and the concept of the Reich". He therefore has the right to have the Bavarian regulation repealed under Article 48 WRV. Nevertheless, he did not carry out this threat; the Bavarian state government found a compromise with the Reich.

On October 9, 1922, President Friedrich Ebert once again called himself the guardian of the constitution. At the time, he rejected (unsuccessfully) a constitutional amendment that outlined (and de facto extended) his term in office. Instead, Ebert wanted to be elected by the people, as the constitution provided for.

On September 12, 1932 there was a sensational parliamentary session, the only one of the Reichstag elected in July. Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen placed an order for dissolution from the Reich President on the table of Reichstag President Hermann Göring ( NSDAP ), while the Reichstag was voting on a vote of no confidence in the government. The next day the “Committee for the Protection of Parliament's Rights” met. Although the Chancellor and Minister of the Interior stayed away from the meeting. The committee therefore decided (against the votes of the DNVP and KPD) that the Reich President had to encourage the members of the government to appear in accordance with the constitution. After all, the Reich President is the “appointed guardian of the constitution”. This declamation had no further consequences.

In November of the same year, Chancellor von Papen asked President Paul von Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag again. This time, however, the Reichstag should not be re-elected within two months, as the constitution provided for. According to Papen, the Reichstag is anti-government and anti-constitutional, which means a state of emergency. As the guardian of the constitution, Hindenburg has the right and the duty to ward off this disturbance of the constitution. In fact, however, Hindenburg changed the Chancellor instead.

The constitutional historian Ernst Rudolf Huber notes a change in the office of the Reich President. Originally it was intended as a pouvoir neutre , a neutral power that rules like a constitutional monarch but does not rule. To do this, the Reich President would have had to remain “outside the field of political action”. With the so-called presidential governments from 1930 onwards, however, the Reich President became the "head of government" and thus vulnerable to political opponents.

"From the position of the mediator and mediator standing above the controversies of the political action groups, from the position of the 'guardian of the constitution', the Reich President stepped over to the front of the forces meeting in the power struggle."

Federal Republic of Germany

The political scientist Wolfgang Rudzio calls the German Federal Constitutional Court the “guardian and designer of the constitution”. For the first time in the United States, a Supreme Court had successfully won the power to review laws to determine whether they were constitutional. While this is only one of its tasks for the American Supreme Court, the principle has prevailed in Europe that a separate court is responsible for the constitutional jurisdiction. After the experiences of the Weimar Republic with anti-democratic mass movements, Germany wanted to withdraw certain principles from mere majority rule. The Federal Constitutional Court has been given particularly extensive competence and is also allowed to review standards independently of individual cases.

Thanks to the abstract control of norms , a political conflict can be transferred directly to a constitutional process, said Rudzio. This usually instigates the opposition in the Bundestag. The accusation arose that the court assumed the role of a substitute legislature. Important areas such as media law are strongly influenced by judge law. Constitutional justice is being politicized, politics is justified.

Overall, however, Rudzio states that the Federal Constitutional Court has “proven itself as an institution protecting the constitution and a barrier to power” and thus contributed to the stability of the political system. The judgments are based on compromises and, like the Federal Council, strengthened the "negotiating democratic traits of the Federal Republic [...]."

The Federal President has certain reserve functions. For example, he sometimes refuses to sign a federal law. But that does not make him a substitute constitutional court, explains Rudzio: For the lack of adequate staff, the Federal President serves at most as the “guardian of the rules of procedure”.

literature

- Carl Schmitt: The Guardian of the Constitution. 5th edition, new edition. Appendix: Hugo Preuß. Its concept of the state and its position in German state theory. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin o. J. (2016), ISBN 978-3-428-14921-6 .

- Oliver Lembcke : Guardian of the Constitution. An institutional theoretical study on the authority of the Federal Constitutional Court. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149157-3 .

supporting documents

- ↑ Carl Schmitt: The Guardian of the Constitution . 5th edition, new edition. Appendix: Hugo Preuß. Its concept of the state and its position in German state theory. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin o. J. (2016), pp. 153–155.

- ↑ Carl Schmitt: The Guardian of the Constitution . 5th edition, new edition. Appendix: Hugo Preuß. Its concept of the state and its position in German state theory. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin o. J. (2016), p. 158.

- ↑ Carl Schmitt: The Guardian of the Constitution . 5th edition, new edition. Appendix: Hugo Preuß. Its concept of the state and its position in German state theory. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin o. J. (2016), pp. 158/159.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume VI: The Weimar Imperial Constitution . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1981, p. 121.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume VII: Expansion, protection and fall of the Weimar Republic . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1984, p. 266.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume VII: Expansion, protection and fall of the Weimar Republic . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1984, pp. 1104/1105.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume VII: Expansion, protection and fall of the Weimar Republic . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1984, p. 1155.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume VI: The Weimar Imperial Constitution . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1981, p. 322.

- ↑ Wolfgang Rudzio: The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany . 9th edition, Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2015 (1983), pp. 298/299.

- ↑ Wolfgang Rudzio: The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany . 9th edition, Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2015 (1983), pp. 306-308.

- ↑ Wolfgang Rudzio: The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany . 9th edition, Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2015 (1983), p. 310.

- ↑ Wolfgang Rudzio: The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany . 9th edition, Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2015 (1983), p. 314.