Herakleion (Egypt)

Coordinates: 31 ° 20 ′ 0 ″ N , 30 ° 9 ′ 0 ″ E

Herakleion ( Greek Ἡράκλειον ), also called Thonis ( Θῶνις , from the ancient Egyptian Taḥont "the sea"), was Egypt's most important seaport after Greece in the two centuries between 550 and 331 BC. Chr. After several disasters the city was finally in the 8th century n. Chr. Under.

history

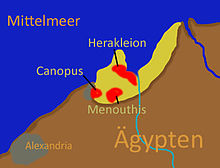

Herakleion lay - next to Menouthis and parts of Canopus - in the Bay of Abukir at a point that is today about 6.5 kilometers off the coast and almost ten meters below sea level. The exact location of the city, known from the texts of Herodotus and Strabo , had been completely forgotten since its fall. It was not until 2001 that the exact location of the ancient city was rediscovered by Franck Goddio and his team. During excavations, inscriptions were found from which it was first recognized that the Greek Herakleion and the Egyptian Thonis were the same city and that in this way both were found at the same time.

Herakleion was built on several islands and crossed by numerous canals, one of which connected the city with the nearby lake, which gave the city its Egyptian name. During the geological survey, which was carried out in parallel to the uncovering in 2001, systems were discovered between the cities of Herakleion and Eastern Canopus, which correspond to the records of ancient texts and show that several settlements actually existed in this now submerged part of Egypt.

In the course of the excavations it was also possible to determine the reasons why the huge buildings of the city had sunk deep in the sand within a very short time. The cause was soil liquefaction as a result of an earthquake , which is dated to the third century BC. Its location on an alluvial floor of Nile mud that was completely soaked through made the city vulnerable to the loss of shear strength from a massive tremor. The main buildings of the city sank into the ground almost intact, including the central temple of Amun . With the loss of the temple, the city, which drew its importance less from trade and more from the spiritual significance of the religious worship of Amun and Osiris, lost its purpose of existence. The city and port lost their recognition and were no longer defended against the constant erosion and relocation of the alluvial fans . In the eighth century AD it was completely abandoned and forgotten.

Heracles Temple

Thonis owes its Greek name Herakleion to the temple of the son of Amun and moon god Chons , who was worshiped here as a healer and oracle god. The Greeks equated the youthful god with Heracles . According to Herodotus, the Temple of Chons is said to have been the first place where Heracles set foot on Egyptian soil. He also reports on the detour of the Trojan Paris and the Greek king's wife Helena to Herakleion on their flight from Menelaus, the jealous ruler of Sparta, shortly before they started the Trojan War . The sanctuary was later dedicated to Amun.

meaning

The city of Herakleion was not only considered one of the most prominent religious centers. She was since the 6th century BC. Chr. Also an active commercial port. The inscription on a stele from the year 380 BC discovered in Naukratis in 1999 proclaimed . BC : "Pharaoh Nectanebos I raises ten percent tariff through his treasury officials in Herakleion on gold, silver, wood and all other goods that come from the sea of the Greeks, also on goods from Naukratis." The importance of the city for sea trade is represented by the numerous docks, canals and more than 70 ancient shipwrecks from the 6th to 2nd centuries BC found in the harbor basin. Documented.

literature

- Hubert Cancik, Helmuth Schneider (ed.): The new Pauly: Enzyklopädie der Antike. Volume 5: Antiquity., Gru - Ing.Metzler , Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-476-01470-3 , p. 471.

- Franck Goddio, Damian Robinson: Thonis-Heracleion in Context. Oxford Center for Maritime Archeology, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-1-905905-33-1 .

- Franck Goddio, Manfred Clauss (eds.), Christoph Gerigk (photos): Egypt's sunken treasures. Prestel, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7913-3828-6 .

- Christophe Thiers: Underwater Archeology in the Canopic Region - La stele de Ptolémée VIII Évergète II à Héracléion. Oxford Center for Maritime Archeology, Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-1-905905-05-8 .

- Sylvie Cauville, Franck Goddio: De la Stèle du Satrape (lignes 14-15) au Temple de Kom Ombo (n ° 950). In: Göttinger Miszellen - Contributions to the Egyptological discussion. Volume 253, 2017, pp. 45-54.

- Lars Abromeit (text), Christoph Gerigk (photos): Atlantis on the Nile, the sunken port city of the pharaohs: how it flourished, how it went down. In: Geo. October 2014.

Web links

- Institut Européen d'Archéologie Sous-Marine (IEASM) - Héracléion

- Franck Goddio's homepage

- “Herakleion: The Resurrection of the Gods” , GEO , No. 12, 2001

- Sunken Herakleion

- Egypt's Sunken Treasures

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Erler, Martin Andreas Stadler (ed.): Platonism and late Egyptian religion. Plutarch and the reception of Egypt in the Roman Empire . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2017, ISBN 978-3-11-053297-5 , p. 245, no.104.

- ^ A b c d Sunken Civilizations: Thonis-Heracleion. From legend to reality . From: franckgoddio.org (Franck Goddio website). Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Exclusif: Premières images de la découverte de la mythique Heracleion (Egypte) . [Photos of the rescue of the statues with a short report (French)] On: eddenya.com ; accessed on July 13, 2020.

- ^ A b c Parker Richards, An Ancient City's Demise Hints at a Hidden Risk of Sea-Level Rise . In: The Atlantic . June 28, 2019.