California Island

Island of California stands for from 16 to mid-18th century continued misunderstanding of Europeans who today Mexican peninsula Baja California held (Baja California) for an island by the Gulf of California is separated from the mainland.

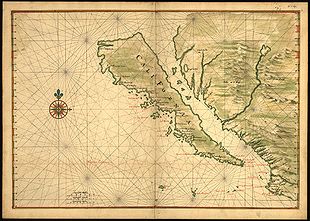

As one of the cartographical errors of history, the image of the "island of California" was spread on many maps of the 17th and 18th centuries, although several explorers had already given information that contradicted this view. The legend was initially influenced by the idea that California was a kind of Garden of Eden , an earthly paradise, comparable to the island of Atlantis .

history

For the history of the discovery of California see also: California (historical landscape)

The first known mention of the legend of the "Island of California" was the romantic story Las sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo - the forerunner of Montalvo's more famous stories of Amadis de Gaula , Esplandian's father. He described the island as follows:

Know that to the right of India is an island called California, which is very close to earthly paradise. It is populated by black women, without a single man among them, because they live like the Amazons .

This description probably led early explorers to believe that the Baja California peninsula was the island from legend.

In 1533 Fortún Ximénez , a mutineer of an expedition sent by Hernán Cortés , discovered the southern part of Baja California, near what is now La Paz . After the discovery, Cortés himself went on an expedition to La Paz. However, the settlement had to be abandoned shortly afterwards. Cortés' limited information about the southern part of the peninsula apparently led to the naming of the region after the legendary "California" and the initial, but short-lived assumption that it was a large island.

In 1539, Cortés sent the helmsman Francisco de Ulloa north along the coast of the Gulf and the Pacific coast of Baja California. Ulloa reached the mouth of the Colorado River at the head of the gulf, which seemed to indicate that it was more of a peninsula than an island. An expedition under Hernando de Alarcón reached the lower Colorado River and confirmed Ulloas' discovery. Maps that were published in Europe from now on, such as the one by Gerardus Mercator and that of Abraham Ortelius , therefore correctly showed Baja California as a peninsula.

Despite these circumstances, the idea of a California island revived in the early seventeenth century. One factor that contributed to this may have been the fictional expeditions of Juan de Fuca in 1592. Fuca claimed to have explored the western coast of North America and found a large opening that may connect to the Atlantic, the legendary Northwest Passage , known in Spanish as the Strait of Anián .

An overland expedition by founding Governor of New Mexico , Juan de Oñate , appears to have played a key role in changing ideas about California . The expedition reached the Colorado River in 1604/1605 and its participants believed they saw the Gulf of California, which continues continuously to the northwest (possibly behind the Sierra Cucapá into the Macuata Basin lagoon).

Reports of Oñate's expedition reached Antonio de la Ascención, a Carmelite brother who had participated in Sebastián Vizcaínos exploration of the west coast of California 1602-1603. Ascención was a staunch propagandist for Spanish settlements in California and in his later writings he referred to California as an island.

The first known reappearance of an island of California on a map dates from 1622 on a map by Michiel Colijn of Amsterdam. This model became the standard for a number of later maps throughout the 17th century and in some cases as late as the 18th century.

The Jesuit missionary and cartographer Eusebio Francisco Kino renewed the idea that Baja California was a peninsula. Kino had accepted the island character of California while studying in Europe, but when he got to Mexico he had doubts. 1698–1706 he undertook a series of land expeditions from northern Sonora to areas in or near the delta of the Colorado River, partly to find a viable route between the Jesuit missions in Sonora and Baja California, but also to solve this geographical issue. Kino came to believe that a land connection must exist and the Jesuits of the 18th century generally followed his example. However, Juan Mateo Manje, a military companion of a number of Kino ventures, had his doubts and European cartographers remained divided on this question.

Jesuit missionaries and explorers in Baja California who tried to finally resolve the issue included Juan de Ugarte (1721), Ferdinand Konščak (1746), and Wenceslaus Linck (1766). The matter was finally decided beyond doubt when Juan Bautista de Anza's expedition toured the area between Sonora and the west coast of California between 1774 and 1776.

outlook

In about 25 million years, Baja California and parts of Southern California will actually be separated from the mainland and become an island due to the tectonic shifts in this area.

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles Chapman: A History of California . New York: MacMillan 1921, pp. 57-58. Here is a translation from the English.

literature

- Don Laylander: Geographies of Fact and Fantasy: Oñate on the Lower Colorado River, 1604-1605 , in: Southern California Quarterly 86: 309-324 (2004).

- Miguel León-Portilla : Cartográfica y crónicas de la antigua California . Coyoacán, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Fundación de Investigaciones Sociales 1989. ISBN 968-6115-06-4

- Glen McLaughlin: The Mapping of California as an Island: An Illustrated Checklist . Saratoga, CA .: California Map Society 1995. ISBN 1-888126-00-0 .

- Dora Beale Polk: The Island of California: A History of the Myth . Arthur H. Clark, Spokane, Washington 1991.

- RV Tooley: California as an Island: A Geographical Misconception Illustrated by 100 Examples from 1625-1770 . Map Collectors' Circle, London 1964.

Web links

- www.philaprintshop.com - Philadelphia Print Shop Ltd. Maps of (Lower) California as an island

- www.loc.gov - California Island ( American Treasures of the Library of Congress )