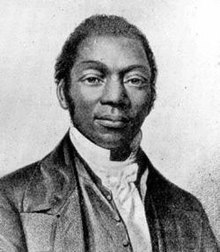

James WC Pennington

James William Charles Pennington (1807-1870) was an African American public speaker, minister , writer, and abolitionist in Brooklyn, New York . When he was 19, he escaped slavery by fleeing western Maryland to New York. After working in Brooklyn and expanding his education, he was accepted into Yale University as the first black student. After completing his studies, he was chosen to ordain pastor for a congregational church and later also for Presbyterian churches , for congregations in Hartford, Connecticut; and New York. After the Civil War, he served communities in Natchez, Mississippi ; Portland, Maine ; and Jacksonville, Florida . In the pre-war period Pennington was an abolitionist among the American representatives at the Second World Conference on Slavery in London.

He wrote The Origin and History of the Colored People (1841), which is considered the first history of black people. His memoir, The Fugitive Blacksmith, was first published in London in 1849.

Early life and education

Born into slavery in 1807 on the Tilghman Plantation on the east coast of Maryland , and named James. When he was four years old, James and his mother were given as a wedding gift to their owner's son, Frisby Tilghman. They came to the younger Tilghman's plantation, called Rockland, near Hagerstown in western Maryland. There James was trained as a carpenter and blacksmith. On October 28, 1827, when he was just 19 years old, James fled the plantation.

After a series of mishaps, James was taken in in Adams County, Pennsylvania by the Quakers William and Phoebe Wright, who offered shelter for the fugitive slave. Due to the fact that James was illiterate, Wright began teaching him to read and write. James took the surname Pennington, after the Qaker Isaac Penington , and the middle name William, after his benefactor.

Move to New York

When Pennington moved to Brooklyn, New York a year later , he found a job as a coachman for a wealthy lawyer. He continued his education, paid his teachers with his own income and taught himself Latin and Greek. The gradual abolition of slavery in New York did not liberate all adults until 1827, so there were still many enslaved day laborers in Kings County and Brooklyn in the early 1800s because they were important to their agricultural economies.

Pennington joined the first Negro National Convention in Philadelphia in 1829 and continued to be active in the Negro Convention movement until he finally became its chief officer in 1853. He had learned so much in five years that he was hired to teach at the school in Newtown, Long Island.

Pennington attended the Shiloh Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. He was accepted as the first black student at Yale University , on the condition that he always had to sit in the back of the classrooms and not ask questions. After graduating from college, Pennington was chosen to ordain a pastor for a congregational church . He first served in a Long Island church .

He was next called in 1840 by Talcott Street Church, now called Faith Congregational Church, located in Hartford . While serving as a pastor, Pennington wrote the first history of African American people, The Origin and History of the Colored People (1841).

He became heavily involved in the abolition movement and was selected to represent the Second World Conference on Slavery in London.

When he returned to Hartford after being invited to preach and serve in English churches, Pennington persuaded his white colleagues to accept him in their pulpit replacements. He was the first black pastor to serve in a number of Connecticut churches.

He befriended John Hooker, one of his parishioners, and in 1844 confided in him his fugitive slave status and concerns about the future. Hooker opened secret negotiations with his former owner Frisby Tilghman, but neither he nor Pennington had the $ 500 demanded for the slave owner, who died a short time later.

Pennington was among those illegally enslaved in search of justice for the West African Mende and involved in the Amistad case , which took place between 1839 and 1841 and was ultimately ended by the United States Supreme Court in favor of the Mende. When the West Africans won the case and their freedom, 35 of them decided to return to Africa. Pennington founded the United Missionary Society, the first black missionary society, to help raise funds for returns.

Pennington was in Scotland when the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed, which increased the threat to him as a fugitive, as it even required the executive in free states to return fugitive slaves to their owners through capture and persecution. Rewards were offered for capturing slaves and the documentation requirements were easy, in favor of the slave captors. Although Pennington was called to New York in 1850 to serve the Shiloh Presbyterian Church, he was afraid of returning at such risk. Hooker worked with the abolitionists in England to raise the money so that he could buy Pennington off the Tilghman's property (the plantation owner had already died). Pennington friends in Duns , Berwickshire raised the money and Hooker quickly "took possession" of Pennington only to be released in the United States.

While Pennington stayed in the British Isles for almost two years for his safety, he traveled extensively both there and in the rest of Europe, giving talks and raising money for abolitionism. He completed his memoir, called The Fugitive Blacksmith , which was first published in London in 1849 and in which he retells his journey from slave to educated pastor. While in Europe, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg .

After returning to the United States, Pennington helped set up a committee to protest the segregation system on streetcars in New York City (including Brooklyn). The schoolteacher Elizabeth Jennings had been arrested in 1854 for insisting on using a train reserved for whites. Various private horse-powered trams excluded blacks or forced them to take their places in the back. Jennings' case was ruled in her favor by the Brooklyn District Court in February 1855.

When Pennington himself was arrested and convicted in 1859 for riding a "whites" tram, he was represented by the Legal Rights Association founded by Elizabeth's father, Thomas L. Jennings. The case successfully challenged the system on the basis of an earlier decision by the United States Supreme Court in 1855 that such a division would be illegal and should end. In around 1865, all car companies removed segregation from their system.

Civil war and subsequent period

Pennington was known as a pacifist, but helped recruit black troops for the Union Army during the Civil War . After the war, he was briefly called to a pastorate in Natchez, Mississippi, and to Portland, Maine for three years .

In early 1870 he was called to Florida by the Presbyterian Church , where he was pastor of an African American congregation in Jacksonville . He died on October 22, 1870, after a brief illness.

Legacies and Honors

In 1849, Pennington was awarded an honorary doctorate from Heidelberg University . The university has founded a community in his honor. It presents a James WC Pennington Award , which honors outstanding scientists who conduct research on topics of particular concern to Pennington. These include slavery and emancipation, peace, education, social reforms, civil rights, religion and intercultural understanding.

Works

- The Origin and History of the Colored People (1841) is considered the first history of black people. Directly challenged because of the inferiority of blacks, he has released testimony from former President Thomas Jefferson .

- The Fugitive Blacksmith (1849), his memoir on his slave past, was first published in London.

literature

- Pennington, James WC: The Fugitive Blacksmith; or, Events in the History of James WC Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States , 2nd ed .. Edition, Charles Gilpin, London 1849. , text online at Documenting the American South , University of North Carolina

- Volk, Kyle G. (2014). Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 148-166. ISBN 0-19-937192-X .

- Webber, Christopher L .: American to the Backbone: The Life of James WC Pennington, the Fugitive Slave Who Became One of the First Black Abolitionists . Pegasus Books, New York 2011, ISBN 1-60598-175-3 .

Web links

- James WC Pennington , Spartacus Educational

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d James WC Pennington, 1807-1870, The Fugitive Blacksmith; "Summary," Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, accessed March 29, 2013

- ^ A b c Pennington, Thomas H. Sands, "Events in the Life of JWC Pennington, DD", an unpublished letter to Marianna Gibbons, Lancaster Historical Society

- ↑ Pennington , p. 43

- ↑ Pennington , p. 52

- ↑ Edward Rothstein, "When Slavery and Its Foes Thrived in Brooklyn 'Brooklyn Abolitionists' Reveals a Surprising History" , New York Times, 16 January 2014, Accessed 16 August 2014

- ^ Bell, Howard Holman (1969) A Survey of the Negro Convention Movement, 1830-1861 . New York, Arno Press

- ↑ Pennington , p. 56

- ^ "Dr. Rev. Pennington," Frederick Douglass' Paper, Aug. 14, 1851.

- ^ New Haven West Association Records, 1734-1909, Vols. 5-6 (1832-1903).

- ↑ Webber , pp. 120-147

- ↑ a b John Hooker, "Rev. Dr. Pennington" , Frederick Douglass' Paper, 26 June 1851

- ↑ Webber , pp. 162-169.

- ↑ Webber , p. 255.

- ↑ Thomas, Herman E. (1995) James WC Pennington: African American Churchman and Abolitionist , Routledge, p. 184, ISBN 0815318898 .

- ^ A b Katherine Greider: The Schoolteacher on the Streetcar , New York Times. November 13, 2005. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "Wholesome Verdict," New York Times, February 23, 1855

- ^ Volk, Kyle G. (2014). Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 148, 150-153, 155-159, 164. ISBN 019937192X .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pennington, James WC |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pennington, James William Charles |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1807 |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1870 |