Julia Stephen

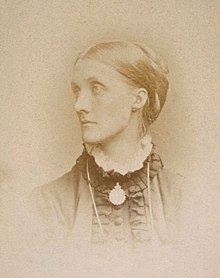

Julia Prinsep Stephen ( February 7, 1846 - May 5, 1895 ), b. Jackson, was an English philanthropist and Pre-Raphaelite model. She was the wife of Leslie Stephen and the mother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell , members of the Bloomsbury Group .

Life

Julia Stephen was born in India . Her family returned to England when she was two years old. She became the preferred model of her aunt, photographer Julia Margaret Cameron , who created over fifty portraits of her. Thanks to another maternal aunt, she began to regularly visit Little Holland House , the seat of an important literary and artistic community at the time. She caught the eye of several Pre-Raphaelite painters who depicted her in her paintings. In 1867 she married Herbert Duckworth, a lawyer in the UK High Court, and shortly thereafter became a widow with three young children. Badly hit, she turned to nursing , philanthropy, and agnosticism. She was drawn to the written work and life of Leslie Stephen, a friend of her sister-in-law Anny Tackeray .

After Leslie Stephen's wife died in 1875, Stephen and Jackson became close friends and married in 1878. They had four other children and lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington , London with Leslie Stephen's seven year old disabled daughter. Many of her seven children and offspring became famous. In addition to family chores and model sitting, Julia Stephens wrote a book in 1883 about her experiences as a nurse, Notes from Sick Rooms . She also wrote children's stories for her family, which were published under the name Stories for Children after her death and were used in the advocacy of social justice . Julia Stephen had strict views about the role of women, namely that their achievements were on par with men, but took place in different spheres. She took a stand against the women's suffrage movement . The Stephens hosted numerous guests at their London home and at their summer residence in St Ives , Cornwall. Ultimately, the chores at home and outside became too much of a burden for Julia Stephen, who finally died at home after falling ill with the flu in 1895 when her youngest child was eleven years old. Author Virginia Woolf provides many insights into the Stephens' domestic life in her autobiographical and fictional works.

activity

Artist model

Stephen's level of awareness is mainly based on her work as an artist model. She not only sat as a model for Pre-Raphaelite painters , but also for her aunt and photographer , Julia Margaret Cameron. Cameron had great faith in her niece and found her very changeable. She documented her moods and brooding in more than 50 portraits, more than of any other subject.

Most of Stephen's pictures were taken between 1864 and 1875. These include a series of side views in the spring of 1867, two of which (310–311) are from her engagement. In these, Cameron Stephens displayed cool, puritanical beauty as a symbol of marriage, which Cameron called "the real honor that I cherish above all". In these images, Cameron framed the bust with flattering sidelights, emphasizing the tightness of Stephen's swan-like neck and the strength of her head. This representation is intended to show the heroism and dignity that a girl is entitled to with marriage. By placing her subject facing the light, Cameron illuminates Stephen and suggests an impending enlightenment.

Cameron often used blurring , as in Julia Duckworth 1867 (Figure 311). One of these portraits is called My Favorite Picture of all my works . In this picture, Stephen's eyes are downcast and averted from the lens, which creates a more soulful effect than the dramatic front views of My niece Julia full face . In this portrait, the subject expressly looks at the photographer as if to say: “I am like you, my own wife.” These portraits offer a contrast to those from her widowhood and mourning for her first husband (1870–1878) with their lean, pale features. In these images, Cameron alludes to another Victorian motif: the tragic heroine whose beauty is destroyed by pain.

Social Activities and Philanthropy

In addition to contributing to the Stephen household and attending to the needs of her family, she also helped friends and supplicants. With a strong sense of social justice , she traveled around London by bus and cared for the sick in hospitals and workhouses . She later reported on her experience as a nurse in her Notes from Sick Rooms (1883). It is a discussion of good grooming practice showing great care for little things. A notable passage is Stephen's description of the misery caused by "crumbs in bed." Her work was not only practical, she was also committed, for example she published a letter of protest on behalf of the inmates of St. George's Union Workhouse in Fulham , condemning her for "submitting to the Temperance Movement and the subsequent reduction of half a beer pint" . This ration, intended for impoverished women , had been removed due to pressure from the temperance activists ( Pall Mall Gazette , October 4, 1879). She often visited this facility. Stephens published two letters under the name Julia Prinsep Stephen, 13, Hyde Park Gate South, on 3 and 16 October 1879. Stephens also wrote a passionate defense for agnostic women ( Agnostic Women , September 8, 1880) in which they Claims that agnosticism is incompatible with spirituality and philanthropy has been denied (see quotations ). She also used her experience as a nurse for the sick and dying in these arguments.

From her home, Virginia Woolf describes how Stephen used one side of the drawing room to give advice and comfort, like an "angel in the house". Angel in the house was the name of a popular poem (1854–1862) by Coventry Patmore of the time that became the metaphor of the ideal woman. Virginia Woolf saw one of the goals of her generation as combating this portrayal - "Killing the angel in the house was one of the occupations of a woman writer," said Woolf in her 1933 essay Professions for Women , which she read to the Women's Service League .

Views

Stephen had strict views on the role of women in society. She was not a feminist and has been described as an anti- feminist . In 1889 she lent her name to the counter-movement of the women's suffrage movement. The novelist Mary Ward (1851-1920) and the political movement Oxford Liberal collected the names of the most prominent intellectual aristocracy, while Stephens girlfriend Octavia Hill (1838-1912), and nearly a hundred other women who called a petition to Appeal Against Female Suffrage ( A Women's Suffrage Claim ) in The Nineteenth Century in June 1889. This earned her an accusation from George Meredith, who mockingly wrote that "it would be the simplicity of a unionist to associate the true Mrs. Leslie with such unreasonable insubordination bring ”, pretending that the signature must belong to another woman of the same name. Stephen was more likely to believe that women had their own roles and role models. She spoke to her daughters of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), Octavia Hill and Mary Ward as role models. Their views on the role of women in society are clearly presented in Agnostic Women : although men and women work in different spheres, their work has the same value. However, Julia's views on women and feminism must be judged by the historical and cultural context in which she lived: she was a thoroughly middle-class Victorian woman.

In Stephen's particular case, the "separate spheres" were reversed in light of the post-industrial convention of that age. Leslie Stephen worked at home and away from home. The views of Stephen and her husband largely coincided with the dominant ethos of their time. Like the "vast majority of their contemporaries, they believed that men and women had different roles in life due to their physiology and upbringing." Despite the segregation of the public and private spheres, Stephen was an advocate for the professionalism and competence of women in these areas, a view that was becoming more common during this time. She set an example of this view with her work as a nurse.

Nor did their views hinder friendship with passionate activists for women's rights and suffrage, such as actress Elizabeth Robins. Robins remembered that her Madonna-like face was somehow misleading: "She was a mixture of Madonna and Lady of the World" and when she said something more urbane it was "so unexpected about that Madonna-like face that you thought it was malicious ". Julia Stephens was, in many ways, a conventional Victorian lady. She defended the hierarchical structure of the servants living in their own home, the need to constantly monitor them, and believed that there was a "close relationship" between the housekeeper and her servants. It was this conventional view, this model of womanhood, that Woolf consciously distanced himself from. She described the Victorian expectation of social conformity as a "machine our rebellious bodies were forced into".

Publications and other writings

Julia Stephens literary canon consists of a book, a collection of children's stories and a number of unpublished articles. The first book was a slim book called Notes from Sick Rooms , published by her husband's publisher, Smith, Elder & Co. in October 1883. It is a narrative of her nurse experience and a detailed instruction booklet. There was a second edition in 1980 and another edition was published along with Virginia Woolfs On Being III (1926) in 2012. The second book is a collection of children's stories called Stories for Children , written between 1880 and 1884. Their stories tended to promote the value of family life and love for animals. In part, the stories reflected tensions in their own lives, as in Cat's Meat . From these papers she appears determined, conservative, and pragmatic with an acumen that almost shocked some people. Although she failed to get these stories published during her lifetime, they were eventually published in 1993 with Notes from Sick Rooms and a collection of her essays in the possession of Quentin Bell. Stephens also wrote a biographical entry for Julia Margaret Cameron in the Dictionary of National Biography , first edited by her husband (1885-1891), one of the rare biographies of women in this work. Virginia Woolf criticized this failure by saying, "It is unfortunate that the Dictionary of National Biography does not contain an entry about maids". Her essays included Agnostic Women, in which she defended her philanthropy as an agnostin, and two other essays on running a household, particularly the treatment of servants.

Virginia Woolf

The detailed examination of Virginia Woolf's literary work has inevitably led to speculation about her mother's influence, including psychoanalytic studies of the mother and daughter. Woolf stated: "my first memory, and actually the most important of all my memories, is that of my mother". Her memories of her mother are memories of an obsession, and she suffered her first severe nervous breakdown after her mother's death in 1895. The loss had other profound, lifelong consequences for her. In many ways the great influence of Virginia's mother is evident in her later memories: “There she is; beautiful, sensitive ... closer than anyone else in our life. She illuminates our random life like with a burning torch, infinitely noble and charming with her children ”. Woolf described her mother as having an "invisible presence" in her life, and Rosenman argues that the mother-daughter relationship is a constant theme in Woolf's work. Rosenman describes that Woolf's modernism must be seen in the light of her ambivalent relationship with her Victorian mother, the center of her previous feminine identity, and her journey to her own sense of independence . For Woolf, "Saint Julia" was both a martyr, whose perfectionism was intimidating, and a source of deprivation, from her real and virtual absence and her early death. Julia's influence and memory permeates Woolf's life and work. "She is following me," she wrote.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kuersten, Ashlyn K .: Women and the law: leaders, cases, and documents . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, Calif. 2003, ISBN 978-0-87436-878-9 .

- ^ Ryle, Robyn .: Questioning gender: a sociological exploration . SAGE / Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks, Calif. 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-6594-1 .

- ^ Cox & Ford, 2003, Plates 279-321 and 328-333

- ↑ a b Cameron 2018, Mrs. Duckworth

- ↑ a b c Cox & Ford 2003, p. 67

- ↑ Kukil 2003, Virginia's mother

- ↑ Cameron 1973, p. 27

- ↑ Thurman 2003

- ↑ Stephen 1883

- ↑ Woolf 2012, Crumbs pp. 57-59

- ↑ Dell 2015, Stephen's writing

- ↑ Stephen 1987, p. 257

- ↑ Dell 2015, Chapter 5, Note 23 p. 188

- ↑ a b Stephen 1987, Agnostic Women pp. 241-247

- ↑ a b c Garnett 2004

- ↑ Woolf 1921

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2014

- ↑ Melani 2011

- ↑ Woolf 1933

- ↑ a b Gillespie 1987a

- ^ Hite 2000

- ↑ Marcus 1981, Introduction p. xix

- ↑ Thomas 1992, p. 79

- ↑ Burstyn 2016, p. 20th

- ↑ Daugherty 2007, pp. 106

- ↑ Woolf 1940

- ^ Broughton 2004, p. 4th

- ↑ Burstyn 2016, p. 23

- ↑ Woolf 1940, p. 90

- ^ Curtis 2002, Virginia p. 197

- ↑ a b Stephen 1987, Servants pp. 248-256

- ↑ Zwerdling 1986, p. 98

- ↑ Woolf 1940, p. 152

- ↑ a b Simpson 2016, p. 12

- ↑ Stephen 1980

- ↑ Woolf 2012

- ↑ Oram 2014

- ↑ Lee 1999, p. 83

- ↑ Bell 1972, p. 34

- ↑ Stephen 1987, Editorial note pp. xviii-xvi

- ↑ Stephen 1987

- ↑ JPS 1886

- ↑ Kukil 2003

- ↑ Woolf 1938 Chapter 2 n. 36

- ^ Broughton 2004, p. 12

- ↑ Minow-Pinkney 2007, pp. 67, 75

- ^ Rosenman 1986

- ↑ Hussey 2007, pp. 91

- ↑ Hirsch 1989, pp. 108 ff

- ↑ Woolf 1940, p. 64

- ↑ Birrento 2007, p. 69

- ↑ Woolf 1940, pp. 81-84

- ↑ Woolf 1908, p. 40

- ↑ Rosenman 1986, cited in Caramagno (1989)

- ↑ Caramagno 1989

- ↑ Woolf 1975, p. 374

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stephen, Julia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Stephen, Julia Prinsep (full name); Jackson, Julia (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English philanthropist and pre-Raphaelite model |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 7, 1846 |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 5, 1895 |